Chagas Disease

- 18 Aug 2025

In News:

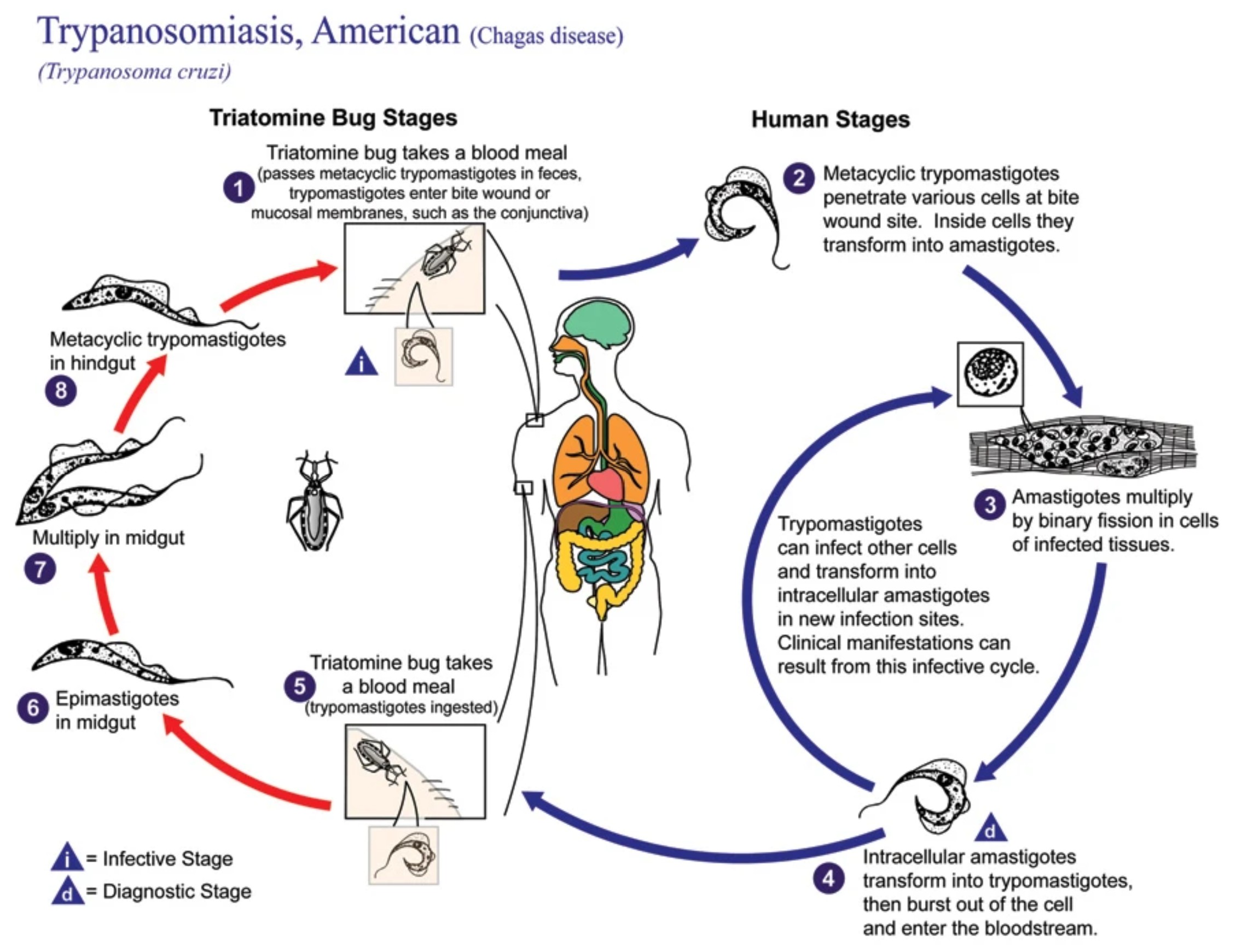

- Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, is an infection caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi and is transmitted primarily through the feces of triatomine bugs—commonly known as “kissing bugs.”

- It can also spread via congenital transmission (from mother to child), contaminated food or water, blood transfusion, organ transplant, or during laboratory handling.

- Though initially endemic to South and Central America, and Mexico, the disease has now emerged as a global health concern, partly due to migration and local vector presence in places like the southern United States.

Clinical Progression & Treatment

- Many infected individuals remain asymptomatic initially, but chronic infection can lead to severe cardiac and digestive complications if left untreated.

- In the acute phase, antiparasitic treatment is aimed at eliminating the parasite. In the chronic phase, therapeutic focus shifts to managing symptoms since parasite clearance becomes difficult.

Alarming Underinvestment in R&D

- R&D investment for Chagas disease is startlingly low—accounting for only 0.6% of all neglected disease research globally.

- This share is even smaller when compared to other tropical diseases: less than US$1 million was spent on new drug development in 2007, constituting a mere 0.04% of neglected disease R&D funding.

- Between 2009 and 2018, US$236 million was invested in Chagas-related R&D—just 0.67% of the total neglected disease investment. Only a handful of funders (NIH, industry, Wellcome Trust) accounted for the majority.

- Patent data reflect this disparity, especially in vaccine development—highlighting significant underinvestment relative to the global health threat posed by Chagas.

- To put it in perspective, malaria receives 20 times more funding than Chagas.

Pathways to Progress

- Innovative Therapies: Research shows promise in novel, low-cost immunotherapeutic agents derived from cyanobacteria that may offer safer and more tolerable options than current drugs.

- Campaigns and Advocacy: Initiatives like the “Chagas: Time to Treat” campaign by DNDi (Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative) emphasize urgent need for:

- Affordable, pediatric formulations

- Safe, field-ready treatments for chronic phases

- Greater public and private funding for R&D.

Broader Significance and Current Calls to Action

- Chagas disease remains among the most neglected tropical diseases, impacting an estimated 6 million people, causing approximately 12,000 deaths annually, and contributing to over 30,000 new cases each year—mainly in Latin America.

- Effective solutions require:

- Improved surveillance and mandatory case notification systems

- Enhanced training and diagnostic tools for health workers

- Integration of One Health approaches (veterinary, environmental control, and human health) in vector management.

- Investment in neglected disease R&D delivers substantial societal returns—studies suggest $1 spent yields $405 in broader economic and health benefits.

Chagas Disease

- 24 Nov 2024

In News:

A recent study by Texas A&M University has uncovered a concerning new risk for dogs in Texas related to Chagas disease—the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi), which causes the disease, can survive in dead kissing bugs (Triatominae). This discovery was published in the Journal of Medical Entomology in October 2024 and has raised alarms about how dead insects, which might be found in insecticide-treated dog kennels, could still pose a transmission risk for dogs.

Key Findings:

- Chagas Disease is primarily spread by kissing bugs, which carry T. cruzi in their gut. Dogs can contract the parasite by ingesting the bug's feces, especially when they lick their bite wounds.

- The study shows that even dead kissing bugs, which are often discarded in kennels, can still carry viable T. cruzi. This is particularly worrying in areas where insecticides are used to control the insects but dead bugs remain accessible to dogs.

- Researchers collected live and dead triatomines from six Texas kennels between June and October 2022, using both genetic testing and culture methods to assess whether the bugs were carrying live T. cruzi.

- 28% of the collected bugs tested positive for T. cruzi.

- A dead kissing bug (Paratriatomalecticularia) was found to still harbor live T. cruzi cultures, demonstrating that the parasite can survive even after the insect has died.

Transmission and Risks:

- Kissing bugs typically feed on the blood of animals like dogs, rodents, and raccoons, defecating near the bite site. If the dog licks the contaminated area, they can ingest the parasite-laden feces and become infected.

- The new discovery suggests that dead kissing bugs may pose a secondary transmission route for T. cruzi. Dogs that ingest these dead bugs, either in insecticide-treated areas or natural environments, could still contract the parasite.

- Researchers noted that dead bugs with intact gut contents showed a higher rate of infection than desiccated ones, which suggests that the condition of the bug after death impacts how long the parasite survives.

Implications for Management:

- The findings challenge current insecticide-based control methods. While insecticides kill the bugs, dead insects could still serve as a source of infection, necessitating new approaches for managing Chagas disease transmission in dog kennels.

- The study underscores the importance of regularly removing dead insects in kennels and reconsidering control strategies beyond just using insecticides.

About Chagas Disease:

- Chagas disease is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite, commonly found in the feces of kissing bugs. It can cause long-term heart and digestive issues if left untreated.

- The disease is common in parts of South America, Central America, and Mexico, but it has been increasingly reported in the southern United States.

- Treatment focuses on killing the parasite in the acute phase, but once it progresses to the chronic phase, treatment is aimed at managing symptoms.

Next Steps and Ongoing Research:

- The Texas A&M team plans to explore how long T. cruzi survives in dead triatomines and whether insecticides affect the parasite’s ability to persist. They are also looking into developing integrated pest management strategies for environments with high kissing bug activity.

- The study also forms part of a broader "One Health" approach, recognizing that both human and animal health are interconnected, and research on Chagas disease in animals can help inform public health strategies.