The High Seas Treaty: Strengthening Global Ocean Governance

- 06 Nov 2025

In News:

The ratification of the High Seas Treaty, formally known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, by over 60 countries in September 2025 marks a watershed moment in global marine governance.

Set to enter into force in January 2026, the treaty seeks to fill long-standing gaps in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982) by creating a comprehensive framework for conserving and sustainably using marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction—waters that comprise nearly two-thirds of the global ocean.

Evolution and Objectives

- The origins of the treaty date back to 2004, when the UN General Assembly recognised the absence of clear guidelines under UNCLOS to protect biodiversity on the high seas and established an ad hoc working group.

- By 2011, states agreed to negotiate four central themes: Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs) including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and capacity building and technology transfer. Four Intergovernmental Conferences held between 2018 and 2023 culminated in a consensus in March 2023, leading to the adoption of the treaty in June 2023.

- The treaty’s overarching goal is to establish an inclusive global governance mechanism to ensure the sustainable use and long-term protection of marine biodiversity, particularly in the context of growing threats such as overfishing, pollution, deep-sea mining, and climate change.

Key Provisions

A cornerstone of the treaty is the recognition of Marine Genetic Resources as the “common heritage of humankind.” MGRs—genetic material from marine organisms that hold immense value for biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and food systems—must be subject to fair and equitable benefit-sharing, both monetary and non-monetary.

The treaty also enables the creation of Area-Based Management Tools, most notably Marine Protected Areas, which will be identified using scientific assessments as well as indigenous and local knowledge. These MPAs aim to conserve critical ecosystems, strengthen climate resilience, and support global food security.

Further, the treaty mandates Environmental Impact Assessments for activities that could have significant, cumulative, or transboundary ecological effects. This introduces transparency and precaution into ocean activities that have previously operated with limited oversight.

To address disparities in ocean science capabilities, the treaty emphasises capacity building and technology transfer, enabling developing countries to participate meaningfully in marine research, monitoring, and governance.

Implementation Challenges

Despite its promise, the High Seas Treaty faces several obstacles. A major conceptual ambiguity exists between the principles of Common Heritage of Humankind and Freedom of the High Seas, the latter guaranteeing unrestricted navigation, scientific exploration, and resource extraction. The treaty applies the common heritage principle only to MGRs, leaving operational uncertainties that may hinder equitable benefit-sharing.

Governance of MGRs remains contentious due to lack of clarity on mechanisms for calculating, distributing, and enforcing benefits, raising concerns over biopiracy by technologically advanced nations and private corporations. Moreover, the absence of major maritime powers such as the United States, China, and Russia from the ratification process undermines the treaty’s universality and enforcement capacity.

Coordination with existing international institutions—including the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs)—is vital to prevent overlapping mandates and fragmented governance. Effective implementation will also require robust monitoring systems, dynamic management of MPAs, transparent data sharing, and substantial financial and technological support for developing countries.

Conclusion

The High Seas Treaty represents one of the most ambitious efforts in international environmental law, seeking to align conservation imperatives with equitable development. Its success will hinge on clear operational guidelines for benefit-sharing and EIAs, stronger institutional coordination, and broader ratification by key maritime states. If implemented with genuine global commitment, the treaty has the potential to transform the governance of the high seas, ensure sustainable access to ocean resources, and enhance the resilience of marine ecosystems at a time of escalating climate and biodiversity crises.

Freshwater Quest: The Emergence of the New Gold Rush

- 11 May 2024

Why is it in the News?

India can take the lead in shaping non-controversial legislative text that addresses the gaps in the laws of the sea, especially in exploratory activities that concern freshwater extraction.

Context:

- Recent statistics reveal that the vast majority of Earth's water is saline, leaving only a small portion as freshwater. Surprisingly, just 0.3% of this freshwater exists in liquid form on the surface, highlighting the significance of subterranean freshwater reserves, including those beneath the ocean floor.

- This emphasizes the growing importance of underground freshwater resources amid the escalating scarcity of surface water.

What are Undersea Freshwater Reserves?

- Undersea freshwater reserves are large volumes of fresh water found beneath the ocean floor.

- In the 1960s, the U.S. Geological Survey made an unexpected discovery of freshwater reserves beneath the ocean floor while drilling off the coast of New Jersey.

- This finding has since been followed by international scientific teams uncovering additional sources of underwater freshwater across the globe, notably including a deep river at the bottom of the Black Sea.

- This particular underwater river is over 100 feet deep, flows at a rate of about four miles per hour, and boasts a volume comparable to some of the world's largest land-based rivers.

- As freshwater resources on land become increasingly scarce, countries are turning their attention towards exploring and potentially exploiting both surface and subsurface freshwater reserves within their maritime zones.

- It is anticipated that these efforts may eventually extend beyond national Exclusive Economic Zones into regions governed by the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention, highlighting the significance of this valuable resource and the increasing need for its sustainable management.

Legal and Policy Framework of Ocean Governance:

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) serves as the primary legal framework governing the management and constitution of the world's oceans.

- It incorporates most internationally recognized maritime laws while also acknowledging the importance of customary international law in sea governance.

- UNCLOS designates the "Area" beyond national jurisdiction as the seabed, ocean floor, and subsoil, defining it as the common heritage of mankind.

- This classification underscores the notion that these regions should be available for the benefit of current and future generations.

- 1958 Geneva Conventions: The 1958 Geneva Conventions on the Law of the Sea also play a vital role in maritime legal doctrine.

- These include the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, the Convention on the High Seas, the Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas, and the Convention on the Continental Shelf.

- These Geneva Conventions address many issues similar to those covered by UNCLOS and draw their principles from customary international law, reinforcing the essential foundations of maritime legal norms.

- Exclusive Economic Zones and the "Area" under UNCLOS: UNCLOS delineates Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) extending up to 200 nautical miles from coastal boundaries, granting states exclusive rights to marine resources within this zone.

- Beyond the EEZ lies the "Area," designated as the common heritage of mankind, managed collectively for sustainable utilization.

Navigating Complexities in UNCLOS and Geneva Conventions:

- The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1958 Geneva Conventions on the Law of the Sea present complex legal interplays due to varying degrees of ratification and overlapping jurisdictions.

- For instance, UNCLOS supersedes the Geneva Conventions for its signatories but does not apply to non-signatory states.

- This divergence in international agreements is exemplified by the United States, which is a signatory to the Geneva Conventions but not UNCLOS.

- The term "resources" under UNCLOS is limited to solid, liquid, or gaseous mineral resources found in the Area.

- However, it remains unclear whether this definition extends to freshwater. Given the increasing scarcity of freshwater resources, potential conflicts may arise over its exploration and extraction in the "Area," particularly in the absence of specific legislation governing resources beyond national jurisdiction.

- The complex legal landscape is further exacerbated by the presence of multiple pieces of maritime legislation that fail to address emerging challenges effectively.

- Additionally, the regulatory authority of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) under UNCLOS adds another layer of complexity, as it remains unclear who regulates state parties to the Geneva Conventions regarding mining and exploratory activities in the "Area.

Significance of Freshwater Exploration for the Future:

- Addressing Scarcity: Given that merely 0.3% of Earth's freshwater is readily available on the surface, the exploration of underground and underwater sources emerges as imperative to satisfy future water demands.

- Conflict Prevention: As freshwater scarcity intensifies, the exploration and protection of underwater sources serve as proactive measures to mitigate potential conflicts over water resources.

- Promoting Sustainability: Engaging in responsible freshwater exploration aligns with Sustainable Development Goals, fostering the sustainable utilization of natural resources to ensure their availability for future generations.

Way Forward:

- Legislative Clarity: It is crucial to create a thorough legal framework that addresses the difficulties of discovering freshwater reserves outside of national borders.

- This framework should harmonize UNCLOS provisions with customary international law, ensuring clarity and consistency in governing maritime activities.

- International Collaboration: Engaging in constructive dialogue and negotiation forums, nations can strive to reconcile divergent legal interpretations and foster mutual understanding.

- Establishing multilateral agreements and protocols can enhance cooperation and coordination in managing underwater freshwater resources.

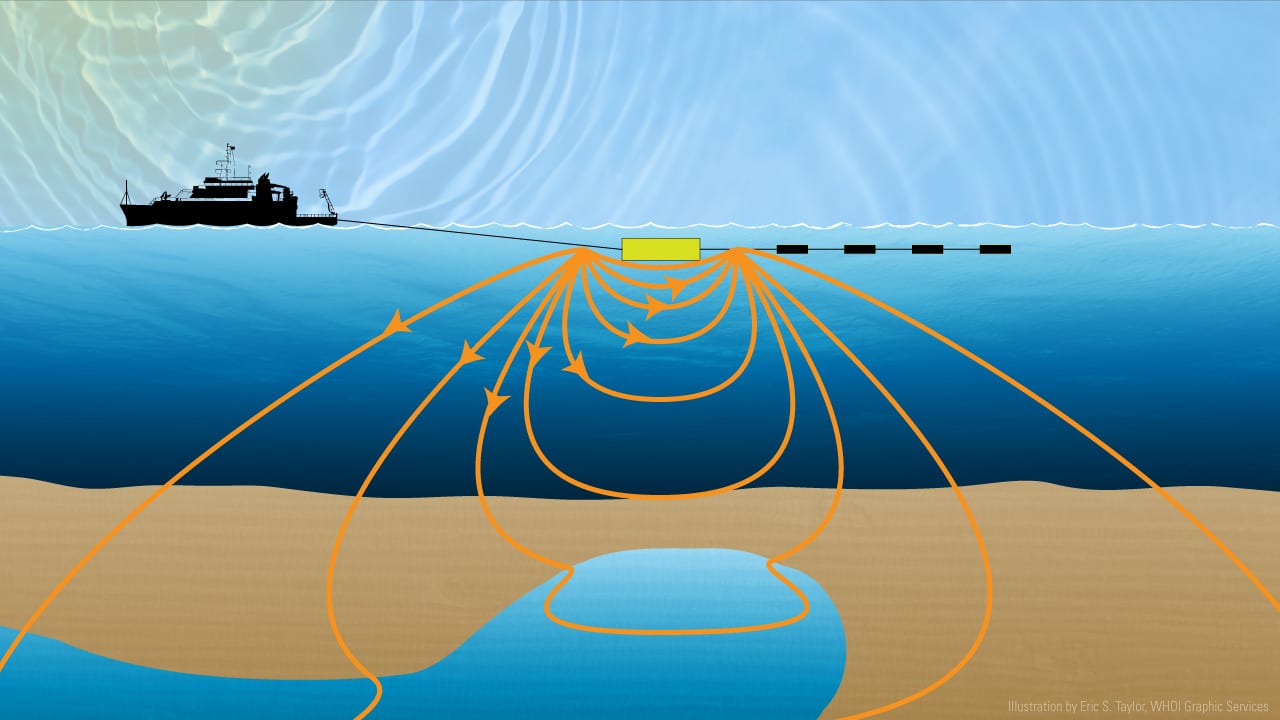

- Research and Technological Advancement: Investment in research and technological innovation is crucial for unlocking the full potential of underwater freshwater reserves.

- Advanced exploration techniques and sustainable extraction methods can optimize resource utilization while minimizing environmental impact.

- India's Leadership Role: As a pivotal stakeholder in maritime affairs, India can spearhead international discourse on freshwater exploration.

- By advocating for inclusive and equitable approaches, India can contribute to the development of global norms and standards governing underwater resource management.

Conclusion

The increasing scarcity of freshwater underscores the urgent need for an internationally recognized legislative framework to govern the exploration and exploitation of underground freshwater resources. The establishment of such a framework would not only help prevent potential conflicts but also ensure the sustainable utilization of this vital resource for the benefit of both present and future generations on a global scale. By proactively addressing these challenges, nations can work together to secure the long-term availability and equitable distribution of freshwater, fostering stability and prosperity in an increasingly water-scarce world.