Reforming India’s Food and Fertiliser Subsidies

- 25 Jun 2025

In News:

India’s food and fertiliser subsidy regime has played a critical role in ensuring food security and supporting farm productivity. However, with extreme poverty declining from 27.1% in 2011 to a historic low of 5.3% in 2022, and the combined food and fertiliser subsidy bill exceeding ?3.5 lakh crore in FY26, there is a growing policy imperative to reimagine these subsidies for greater efficiency, fiscal prudence, and long-term sustainability.

The Current Landscape

Food and fertiliser subsidies in India are a mix of direct and indirect support mechanisms. Direct subsidies include schemes like PM-KISAN, while indirect subsidies include low-cost foodgrains under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and price-controlled fertilisers. As per government data:

- Food subsidy is budgeted at ?2.03 lakh crore, reaching over 800 million beneficiaries through the Public Distribution System (PDS).

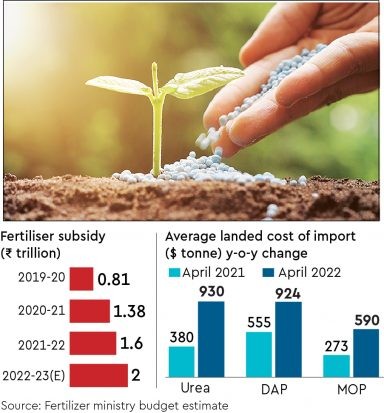

- Fertiliser subsidy is pegged at ?1.56 lakh crore, driven by rising global prices and a skewed demand for urea.

Challenges in the Current Subsidy System

- Mismatch Between Poverty and Coverage: Despite poverty falling to 5.3%, 84% of households still possess ration cards, many of whom are no longer poor. This reflects poor targeting and leads to welfare leakages.

- Nutritional Deficiency in PDS: The PDS remains cereal-centric, primarily distributing rice and wheat, while nutrition insecurity persists due to insufficient supply of pulses, edible oils, and micronutrients.

- Fertiliser Misuse: The overuse of nitrogen-based fertilisers (particularly urea) has caused an ecological imbalance, deteriorating soil health and reducing long-term farm productivity.

- Fiscal Constraints: Massive subsidy expenditures are crowding out investments in rural infrastructure such as irrigation, cold storage, and extension services—critical for doubling farmer incomes.

- Leakages and Ghost Beneficiaries: Despite digitisation and Aadhaar seeding, leakages continue in both PDS and fertiliser channels, with instances like card cancellations in Jharkhand pointing to persistent inefficiencies.

Government Initiatives So Far

- PMGKAY during COVID-19 extended free foodgrains to NFSA beneficiaries, and has now been merged with NFSA provisions.

- Digitisation of ration cards and Aadhaar-enabled ePoS machines are being used to plug PDS leakages.

- Neem-coated urea and the Nutrient-Based Subsidy (NBS) policy aim to reduce misuse and promote balanced fertilisation.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) for fertilisers is being piloted to streamline subsidy flows and reduce diversion.

Reform Measures Needed

- Targeting and Gradation: Use PM-KISAN, SECC, and Aadhaar-linked databases to better identify the poorest 15% households and gradually taper subsidies for others.

- Digital Food Coupons: Introduce ?700/month digital wallets or coupons for nutrient-rich food purchases (pulses, eggs, milk), improving dietary diversity and nutrition security.

- Fertiliser Coupons & Price Rationalisation: Introduce fertiliser coupons, deregulate prices, and incentivise eco-friendly inputs like bio-fertilisers and organic compost.

- Improve Monitoring: Strengthen data triangulation using land records, crop surveys, and income data to reduce inclusion/exclusion errors.

- Farmer Sensitisation: Communicate the rationale for reforms clearly to farmers to avoid mistrust or resistance, as witnessed during earlier protests.

Conclusion

India’s welfare architecture must evolve with its changing socio-economic landscape. With poverty rates at historic lows, continued universal subsidies are both fiscally unsustainable and inefficient. Smartly targeted reforms in food and fertiliser subsidies are vital for improving nutritional outcomes, restoring soil health, and ensuring optimal allocation of public resources. A calibrated transition to a more efficient, inclusive, and sustainable system will enhance welfare delivery without compromising economic growth.