New Seeds Bill 2025

- 02 Dec 2025

In News:

The Union Government has introduced the Draft Seeds Bill, 2025 to modernise India’s seed regulatory system and replace the Seeds Act, 1966 and the Seeds (Control) Order, 1983. The proposed law seeks to address long-standing regulatory gaps, improve seed quality, curb the sale of spurious seeds, and align the legal framework with the evolving needs of Indian agriculture.

Why a new law was needed?

The Seeds Act, 1966 regulates only notified varieties, and registration of seeds has not been mandatory. Several categories such as green manure seeds, plantation crops, and certain commercial crops remained outside its ambit. Moreover, penalties under the old law were minimal a maximum of six months’ imprisonment and a fine of ?1,000 offering little deterrence in a rapidly expanding and commercialised seed market.

Concerns about the prevalence of substandard and fake seeds have grown in recent years. Between 2022 and 2025, authorities tested nearly six lakh seed samples, of which over 43,000 were found non-standard, prompting warnings, stop-sale orders, and legal cases. These trends highlighted the need for a stronger regulatory architecture.

India’s Seed Sector Context

India’s annual seed requirement for 2024–25 is estimated at about 48 lakh tonnes, while availability exceeds demand. The seed market is valued at roughly ?40,000 crore. Over 3,000 new crop varieties have been released in the past decade, with the public sector contributing the majority, though private participation is rising. This expansion has increased the need for quality assurance, traceability, and uniform standards.

Key Provisions of the Draft Seeds Bill, 2025

A central feature of the Bill is mandatory registration of all seed varieties before sale, except for traditional farmers’ varieties and seeds meant exclusively for export. New varieties must undergo Value for Cultivation and Use (VCU) testing across multiple locations to establish performance and suitability. Only seeds meeting prescribed standards of germination, genetic purity, and quality can enter the market.

The Bill also strengthens market regulation and traceability. Seed dealers must obtain registration from state authorities, and seed containers will carry QR codes linked to a central seed traceability portal to enable tracking across the supply chain. A Central Accreditation System is proposed to allow nationally accredited entities to operate across states, reducing multiple approvals.

Penalties are significantly enhanced. Minor violations attract monetary fines, while major offences such as selling spurious or unregistered seeds can lead to fines up to ?30 lakh and imprisonment up to three years. The government states that this will deter malpractice while protecting farmers.

The Bill affirms farmers’ rights to save, use, exchange, and sell farm-saved seeds, provided they are not marketed under a brand name. New central and state seed committees are envisaged to oversee implementation.

Concerns and Criticisms

Despite its reform intent, the Bill has drawn criticism from farmer groups and civil society. A major concern is the absence of a simple compensation mechanism for farmers affected by crop failure due to faulty seeds, leaving them dependent on lengthy legal processes.

Community seed keepers, such as Farmer Producer Organisations and traditional seed networks, may be treated as commercial entities, increasing compliance burdens. Critics argue that VCU testing norms may favouruniform hybrid varieties produced by large firms, potentially marginalisingindigenous and climate-resilient varieties. Digital compliance requirements, including QR tracking and online reporting, could also disadvantage small, resource-poor stakeholders.

Some experts also caution that recognition of foreign testing data may ease the entry of imported or genetically engineered seeds without robust domestic scrutiny.

Conclusion

The Draft Seeds Bill, 2025 represents a significant attempt to modernise India’s seed governance by emphasising quality control, traceability, and stricter penalties. However, its ultimate effectiveness will depend on balancing regulatory oversight with farmers’ rights, biodiversity conservation, and equitable access, ensuring that reform strengthens both productivity and sustainability in Indian agriculture.

Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Agricultural Transformation

- 28 Nov 2025

In News:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is emerging as a powerful enabler of transformation across agrifood systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where smallholder farmers produce nearly one-third of the world’s food. The World Bank–led report “Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Agricultural Transformation” highlights how AI, if deployed responsibly and inclusively, can enhance productivity, climate resilience, and equity while cautioning that technology alone is insufficient without enabling investments and governance.

AI and the Changing Agrifood Landscape

Recent trends show a decisive shift from isolated digital pilots to systems-level AI adoption across the entire agricultural value chain. Advances in Generative AI and multimodal models combining text, images, satellite data and sensor feeds are enabling natural-language advisories in local languages and predictive insights for farmers. Investments in AI for agriculture are rising rapidly, with the market projected to grow from about US$1.5 billion in 2023 to over US$10 billion by 2032. Importantly, LMIC-focused innovations such as lightweight “small AI” models on smartphones and offline devices are expanding reach in low-connectivity settings.

Opportunities Across the Value Chain

AI applications span crops, livestock, advisory services, markets and finance. In production, AI accelerates research on climate-resilient seeds and breeding, improves pest detection, precision irrigation and nutrient management cutting chemical use significantly while raising yields. In farm management, real-time soil and weather analytics help farmers make data-driven decisions. Market-facing tools enhance price forecasting, traceability and logistics, reducing post-harvest losses and improving transparency. AI also expands inclusive finance through alternative credit scoring and climate-indexed insurance, bringing formal financial services to previously unbanked smallholders. For governments, AI strengthens early-warning systems, yield and price forecasting, and targeted subsidies, improving food security planning.

Emerging Initiatives

Several initiatives demonstrate AI’s promise. International research centres use machine learning and computer vision to speed up phenotyping and genebank screening, multiplying throughput while reducing costs. Data coalitions and agricultural data exchanges in countries like Ethiopia and India are creating shared, sovereign data layers to train local models. Public–private platforms in Africa and India are piloting multilingual AI advisory services, reaching tens of thousands of farmers and showing gains in income, quality and input efficiency.

Key Challenges

Despite its potential, AI adoption faces serious constraints. Digital infrastructure gaps limited broadband, electricity and devices restrict real-time deployment in rural areas. Data scarcity and bias, with training datasets dominated by high-income regions, risk producing irrelevant or exclusionary recommendations. Low digital literacy and trust, especially among women and older farmers, can slow uptake. Weak regulatory frameworks on data ownership, privacy, transparency and liability create uncertainty, while there is a risk that AI may deepen inequalities by favouring large agribusinesses or locking users into proprietary platforms.

Way Forward

To harness AI responsibly, countries must adopt national AI strategies with a clear agricultural focus, aligned to food security, climate adaptation and nutrition goals. Investments in digital public infrastructure and rural connectivity are essential. Building open, interoperable and FAIR data ecosystems through agricultural data exchange nodes will enable context-specific models. Equally important are capacity-building and extension reforms, using local-language, multimodal interfaces. Finally, robust ethical and governance frameworks, developed through participatory processes and regulatory sandboxes, are vital to ensure accountability and inclusion.

Conclusion

AI can significantly boost agricultural productivity, resilience and incomes, but only if embedded within broader reforms in infrastructure, skills, data and governance. Used ethically and inclusively, AI can complement traditional agricultural transformation and support long-term food security and environmental sustainability.

Draft Seeds Bill 2025: Reforming India’s Seed Regulatory Framework

- 16 Nov 2025

In News:

The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare has released the Draft Seeds Bill 2025 for public consultation, proposing a comprehensive overhaul of India’s seed governance architecture. The Bill seeks to replace the outdated Seeds Act, 1966 and the Seeds (Control) Order, 1983, reflecting the need to align India’s seed sector with contemporary agricultural technologies, global market trends, and quality assurance norms. Earlier attempts to introduce new seed legislation in 2004 and 2019 faced widespread farmer resistance and were ultimately withdrawn. The 2025 draft attempts a more balanced approach that strengthens quality standards while safeguarding farmers’ rights.

A central objective of the Bill is to ensure quality, affordability, and traceability of seeds. It mandates regulatory oversight over the sale, import, export, and distribution of seeds, requiring conformity to the Indian Minimum Seed Certification Standards, which define minimum limits for germination, genetic purity, physical purity, seed health, and trait expression. This shift aims to curb the rampant sale of substandard and spurious seeds that have often resulted in crop losses for farmers.

A defining feature of the Bill is the introduction of mandatory registration for all seed varieties, except farmers’ varieties and varieties produced exclusively for export. Existing notified varieties under the 1966 Act will be deemed registered, ensuring continuity while improving accountability. Registration of seed dealers and distributors with State authorities is also compulsory, bringing uniformity and transparency into the seed supply chain. The Bill also allows controlled liberalisation of seed imports, enabling entry of unregistered varieties for research and trials, with the aim of promoting innovation and access to global germplasm.

The draft introduces a graded penalty structure, classifying offences into trivial, minor, and major categories. Major offences include the sale of non-registered or spurious seeds and operating without proper registration. These attract stiff penalties of up to ?30 lakh and imprisonment of up to three years, signalling the government’s intent to curb malpractice. Minor offences are proposed to be decriminalised to encourage compliance and enhance ease of doing business for legitimate seed enterprises.

Institutionally, the Bill provides for Central and State Seed Committees to coordinate policy, regulate certification procedures, and oversee enforcement mechanisms. This is expected to strengthen federal-level harmonisation in an area where seeds fall under central regulation, but agriculture remains a State subject.

Stakeholder responses to the draft have been mixed. Seed industry associations have welcomed the Bill, highlighting that it will modernise the regulatory environment, support innovation, and bring clarity to seed registration norms. The Federation of Seed Industry of India (FSII) has endorsed its emphasis on research-driven seed development. However, farmer organisations continue to express apprehension, viewing the Bill as potentially “pro-corporate,” with fears of increased dependence on private and multinational companies. Concerns persist regarding compliance burdens for small producers and the potential dilution of farmers’ autonomy in seed selection and exchange.

To ensure the Bill’s effective implementation, several challenges need to be addressed—strengthening laboratory and certification infrastructure, harmonising central–state coordination, ensuring transparency in seed testing, and safeguarding farmers’ traditional rights to save, use, exchange, and sell their own varieties (except branded seeds). Additionally, enhancing investments in public sector seed research through ICAR and State Agricultural Universities remains crucial to balance private sector dominance.

In conclusion, the Draft Seeds Bill 2025 represents a significant step toward modernising India’s seed regulatory ecosystem. Its success will depend on inclusive stakeholder consultations, robust enforcement mechanisms, and a regulatory framework that balances farmer protection with innovation and industry growth.

Changing Patterns in Agricultural Output

- 04 Jul 2025

In News:

The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) recently released the “Value of Output from Agriculture and Allied Sectors” report (June 2025), revealing significant structural changes in India’s agricultural production and consumption over the past decade. The data reflects a shift away from staple cereals toward high-value crops such as fruits, vegetables, and spices—mirroring broader socio-economic transformations.

Key Findings: Rise of High-Value Crops

The Gross Value of Output (GVO)—the total value of agricultural production before deducting input costs—highlights changing food habits and production priorities. Between 2011–12 and 2023–24, the GVO of several non-traditional crops rose sharply. For example:

- Strawberries saw a 40-fold rise in GVO at constant prices (from ?1.32 crore to ?55.4 crore), and nearly 80-fold at current prices.

- Pomegranate GVO quadrupled to ?9,231 crore.

- Parmal (parwal) and pumpkin increased by 17 and 10 times, respectively.

- Mushroom and dry ginger witnessed 3.5x and 285% growth, the latter aided by improved agro-processing infrastructure.

This transformation indicates increasing demand for horticultural and niche crops with higher returns, aligning with government focus on nutritional security and export diversification.

Declining Importance of Cereals

Contrasting the rise of high-value crops is the decline in cereal dominance. The share of cereals in agricultural GVO fell from 17.6% (2011–12) to 14.5% (2023–24). Simultaneously, consumption data shows cereals’ share in urban MPCE dropped from 6.61% to 3.74%, and in rural MPCE from 10.69% to 4.97% over the same period. This trend aligns with Engel’s Law, where rising incomes lead to a shift in spending from staples to diversified food categories.

Rising Animal Product Consumption

The share of meat in agricultural GVO increased from 5% to 7.5%, reflecting higher protein intake as incomes grew. However, its GVO growth (131%) was still lower than that of some horticultural produce like strawberry (4,000%).

Changing Consumption Patterns

Data from the 2023–24 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) supports this structural shift. The share of fresh fruits in rural MPCE rose slightly from 2.25% to 2.66%, while in urban areas it slightly declined. Yet, a 2024 study co-authored by Shamika Ravi indicates broader accessibility, with the proportion of rural households consuming fresh fruits increasing from 63.8% to 90.3%, especially among the bottom 20% income group.

Policy and Economic Implications

This transition from staple grains to high-value crops is driven by technological advancements, shifting consumer preferences, nutritional awareness, export potential, and government support for crop diversification. It reflects a move toward a more resilient, market-oriented agricultural system.

However, challenges remain in ensuring equitable access to high-value markets, stabilizing prices, and addressing risks associated with monoculture trends.

Conclusion

The MoSPI data reveals a critical inflection point in Indian agriculture. While traditional staples are declining in prominence, the rise of high-value horticulture and livestock signals both economic opportunity and the need for targeted policy to support inclusive, nutrition-sensitive agricultural growth.

Statistical Report on Value of Output from Agriculture and Allied Sectors (2011–12 to 2023–24)

- 02 Jul 2025

In News:

The National Statistics Office (NSO), under the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, released its annual publication, Statistical Report on Value of Output from Agriculture and Allied Sectors (2011–12 to 2023–24). This comprehensive report provides granular data on output values across crop, livestock, forestry, and fisheries sectors at both current and constant (2011–12) prices, offering crucial insights into trends, sectoral contributions, and regional dynamics in Indian agriculture.

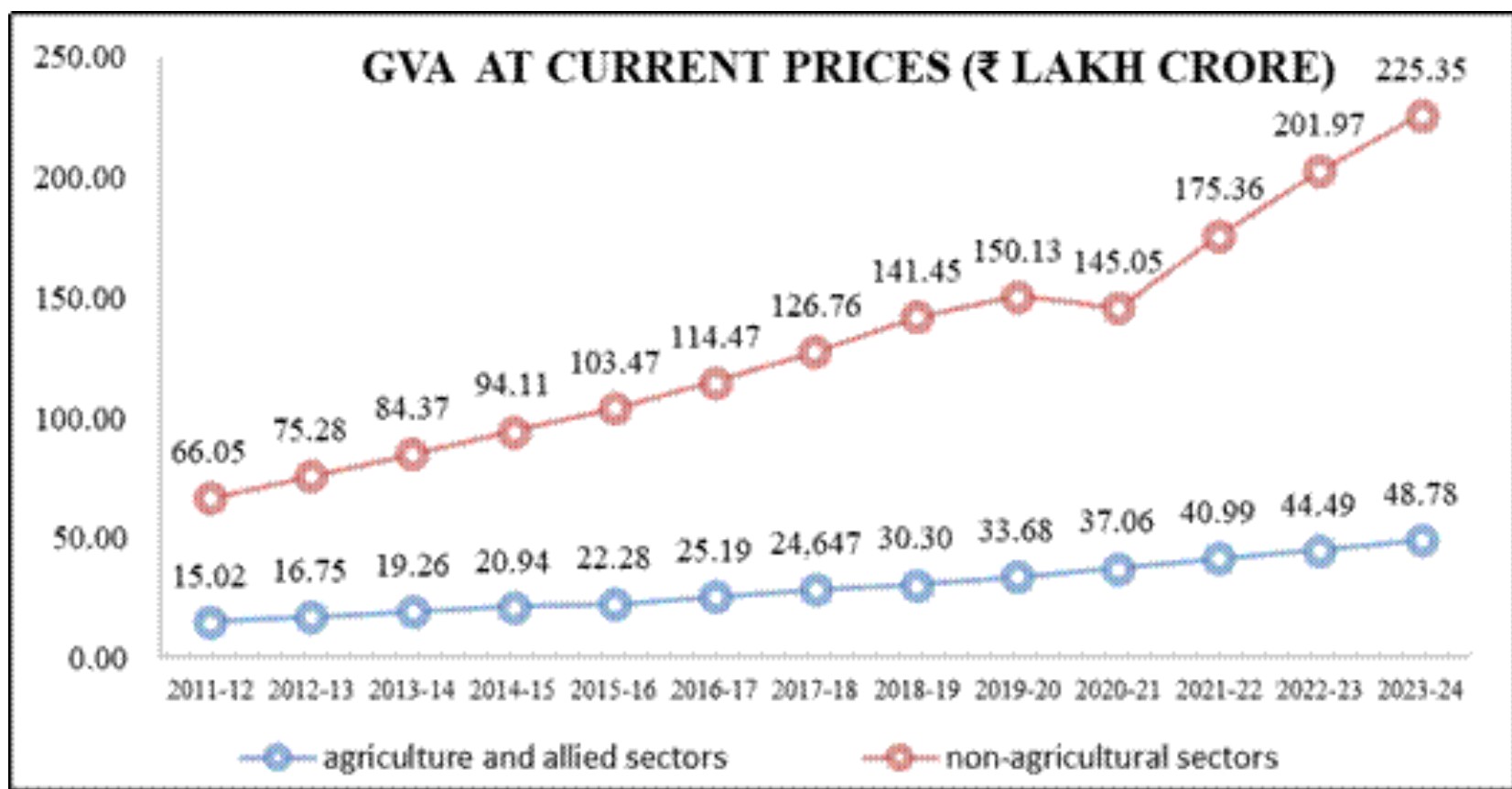

Growth Trajectory and Sectoral Contributions

The Gross Value Added (GVA) of agriculture and allied sectors at current prices rose by 225%, from ?1,502 thousand crore in 2011–12 to ?4,878 thousand crore in 2023–24. At constant prices, the Gross Value of Output (GVO) increased by 54.6%, from ?1,908 thousand crore to ?2,949 thousand crore during the same period.

The crop sector remained the backbone of the agricultural economy, contributing ?1,595 thousand crore or 54.1% of the total GVO in 2023–24. Within this, cereals and fruits & vegetables together formed 52.5% of the crop output. Notably, paddy and wheat alone accounted for 85% of cereal GVO. Five states—Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Telangana, and Haryana—contributed 53% of the total cereal output, with Uttar Pradesh maintaining its top position despite a decline in share from 18.6% to 17.2%.

Shifting Dynamics in Horticulture

The horticulture sector has witnessed dynamic changes. In fruits, banana (?47,000 crore) surpassed mango (?46,100 crore) in 2023–24, breaking mango’s longstanding dominance. In the vegetable group, potato retained its lead, with GVO rising from ?21,300 crore to ?37,200 crore between 2011–12 and 2023–24.

Floriculture emerged as a growing commercial interest, with its GVO nearly doubling from ?17,400 crore to ?28,100 crore. The shifts in leading states in the production of fruits, vegetables, and floriculture underscore regional diversification in agricultural growth.

Rise of Livestock and Allied Sectors

The livestock sector experienced substantial growth, with its GVO nearly doubling from ?488 thousand crore to ?919 thousand crore. While milk remained the dominant product, its share slightly decreased from 67.2% to 65.9%, whereas meat products increased their share from 19.7% to 24.1%.

In the condiments and spices category, Madhya Pradesh emerged as the top contributor with a 19.2% share, followed by Karnataka (16.6%) and Gujarat (15.5%).

The forestry and logging sector saw a moderate increase in GVO from ?149 thousand crore to ?227 thousand crore. Significantly, the share of industrial wood surged from 49.9% to 70.2%, indicating growing commercialization.

Emerging Importance of Fisheries

The fishing and aquaculture sector is becoming increasingly vital, with its contribution to total agricultural GVO rising from 4.2% to 7.0% over the period. While inland fish share declined from 57.7% to 50.2%, marine fish increased from 42.3% to 49.8%. States like West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh witnessed substantial structural shifts in fisheries production patterns.

Reforming India’s Food and Fertiliser Subsidies

- 25 Jun 2025

In News:

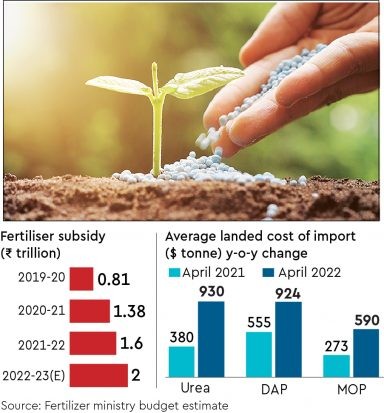

India’s food and fertiliser subsidy regime has played a critical role in ensuring food security and supporting farm productivity. However, with extreme poverty declining from 27.1% in 2011 to a historic low of 5.3% in 2022, and the combined food and fertiliser subsidy bill exceeding ?3.5 lakh crore in FY26, there is a growing policy imperative to reimagine these subsidies for greater efficiency, fiscal prudence, and long-term sustainability.

The Current Landscape

Food and fertiliser subsidies in India are a mix of direct and indirect support mechanisms. Direct subsidies include schemes like PM-KISAN, while indirect subsidies include low-cost foodgrains under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and price-controlled fertilisers. As per government data:

- Food subsidy is budgeted at ?2.03 lakh crore, reaching over 800 million beneficiaries through the Public Distribution System (PDS).

- Fertiliser subsidy is pegged at ?1.56 lakh crore, driven by rising global prices and a skewed demand for urea.

Challenges in the Current Subsidy System

- Mismatch Between Poverty and Coverage: Despite poverty falling to 5.3%, 84% of households still possess ration cards, many of whom are no longer poor. This reflects poor targeting and leads to welfare leakages.

- Nutritional Deficiency in PDS: The PDS remains cereal-centric, primarily distributing rice and wheat, while nutrition insecurity persists due to insufficient supply of pulses, edible oils, and micronutrients.

- Fertiliser Misuse: The overuse of nitrogen-based fertilisers (particularly urea) has caused an ecological imbalance, deteriorating soil health and reducing long-term farm productivity.

- Fiscal Constraints: Massive subsidy expenditures are crowding out investments in rural infrastructure such as irrigation, cold storage, and extension services—critical for doubling farmer incomes.

- Leakages and Ghost Beneficiaries: Despite digitisation and Aadhaar seeding, leakages continue in both PDS and fertiliser channels, with instances like card cancellations in Jharkhand pointing to persistent inefficiencies.

Government Initiatives So Far

- PMGKAY during COVID-19 extended free foodgrains to NFSA beneficiaries, and has now been merged with NFSA provisions.

- Digitisation of ration cards and Aadhaar-enabled ePoS machines are being used to plug PDS leakages.

- Neem-coated urea and the Nutrient-Based Subsidy (NBS) policy aim to reduce misuse and promote balanced fertilisation.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) for fertilisers is being piloted to streamline subsidy flows and reduce diversion.

Reform Measures Needed

- Targeting and Gradation: Use PM-KISAN, SECC, and Aadhaar-linked databases to better identify the poorest 15% households and gradually taper subsidies for others.

- Digital Food Coupons: Introduce ?700/month digital wallets or coupons for nutrient-rich food purchases (pulses, eggs, milk), improving dietary diversity and nutrition security.

- Fertiliser Coupons & Price Rationalisation: Introduce fertiliser coupons, deregulate prices, and incentivise eco-friendly inputs like bio-fertilisers and organic compost.

- Improve Monitoring: Strengthen data triangulation using land records, crop surveys, and income data to reduce inclusion/exclusion errors.

- Farmer Sensitisation: Communicate the rationale for reforms clearly to farmers to avoid mistrust or resistance, as witnessed during earlier protests.

Conclusion

India’s welfare architecture must evolve with its changing socio-economic landscape. With poverty rates at historic lows, continued universal subsidies are both fiscally unsustainable and inefficient. Smartly targeted reforms in food and fertiliser subsidies are vital for improving nutritional outcomes, restoring soil health, and ensuring optimal allocation of public resources. A calibrated transition to a more efficient, inclusive, and sustainable system will enhance welfare delivery without compromising economic growth.

The Rising Cost of Imports: A Concern for India's Food Security and Farmers

- 21 Jun 2025

In News:

India’s increasing dependence on imports of pulses and edible oils has raised serious concerns about agricultural sustainability, trade deficits, and farmer welfare. Despite policy claims of self-reliance in agriculture, recent trends highlight structural imbalances in domestic production and pricing mechanisms, especially for pulses and oilseeds.

Farmers at the Receiving End

Farmers cultivating pulses and oilseeds, such as moong, chana, masoor, and soyabean, are struggling due to poor price realization and lack of systematic procurement at Minimum Support Prices (MSP). Rao Gulab Singh Lodhi, a farmer from Madhya Pradesh, harvested 90 quintals of moong in summer 2025. Despite an MSP of ?8,682/quintal, he had to sell his produce in the open market at ?6,000/quintal due to the absence of procurement infrastructure. Soyabean prices, too, are well below MSP, selling at ?4,100–4,200/quintal against an MSP of ?5,328 (for 2025–26).

Unlike rice and wheat, for which procurement is extensive and assured, pulses and oilseeds lack institutional support, even in regions where agro-climatic conditions favour their cultivation. This discourages farmers from growing these critical crops, despite using high-yielding and climate-resilient varieties.

Pulses: From Self-Reliance to Import Surge

India witnessed a record 7.3 million tonnes (mt) of pulses imports worth $5.5 billion in 2024–25, surpassing the previous high of 6.6 mt in 2016–17. This comes after years of reduced imports, thanks to improved domestic production which had peaked at 27.3 mt in 2021–22.

However, the El Niño-induced drought in 2023–24 brought down production to 24.2 mt, leading to higher retail inflation in pulses and prompting duty cuts on imports. While these imports helped control prices—with CPI inflation in pulses falling to –8.2% by May 2025—they also depressed mandi prices. In Maharashtra, arhar and chana are currently trading below MSPs, impacting farmer incomes.

Major pulse imports in 2024–25 included:

- 2.2 mt of yellow/white peas (Canada, Russia),

- 1.6 mt of chana (Australia),

- 1.2 mt each of arhar and masoor (Africa, Canada, Australia),

- 0.8 mt of urad (Myanmar, Brazil).

Edible Oils: Worsening Import Dependency

India’s vegetable oil imports more than doubled in a decade—from 7.9 mt in 2013–14 to 16.4 mt in 2024–25. In value terms, imports jumped from $7.2 billion to $20.8 billion, driven partly by global supply disruptions (e.g., Russia-Ukraine war) and high domestic consumption.

India now imports over 60% of its edible oil needs, with palm (7.9 mt), soyabean (4.8 mt), and sunflower oil (3.5 mt) forming the bulk. In May 2025, CPI inflation for vegetable oils stood at 17.9%. In response, the Centre slashed import duties on crude palm, soyabean, and sunflower oil from 20% to 10%, reducing the overall tariff to 16.5%.

While the move may lower consumer prices, industry bodies like the Soyabean Processors Association of India have warned it will "flood the market with cheap imports", making domestic oilseed cultivation less viable. Farmers may shift to alternative crops in the coming kharif season, further weakening India’s self-sufficiency goals.

Conclusion

India’s growing import reliance for essential food commodities like pulses and edible oils, coupled with poor farm-level price realization and weak procurement systems, undermines the objectives of food security and self-reliance. Sustainable import substitution must be driven by robust domestic production incentives, fair pricing mechanisms, and resilient procurement frameworks—especially for non-cereal crops.

Overfishing in India

- 23 May 2025

Context:

India, the second-largest fish-producing nation globally, contributes around 8% to world fish production. With an estimated marine fisheries potential of 5.31 million tonnes, India’s sector has reached its maximum sustainable yield, currently stabilizing at 3–4 million tonnes annually. However, this apparent success masks deep ecological and socio-economic distress, primarily due to overfishing.

Inequity and Overexploitation

Despite their 90% share in the fishing population, small-scale fishers harvest merely 10% of the total catch, while mechanised trawlers dominate volumes. This has left three-fourths of marine fisher families below the poverty line. Escalating the problem is the race to increase yields using more powerful engines and finer mesh nets—leading to marginal gains at steep ecological and financial costs.

Trawling operations, especially shrimp trawlers, demonstrate the magnitude of bycatch—where for every kilogram of shrimp, over 10 kg of juvenile and non-target species are discarded. Such practices degrade marine biodiversity, deplete spawning stocks, and destabilise food webs. Examples from Canada’s cod fishery (1992) and California’s sardine fishery collapse (1960s–80s) show the irreversible impacts of mismanaged stocks.

Policy Fragmentation and Regulatory Loopholes

Each coastal state in India governs its marine fisheries through its own Marine Fisheries Regulation Act (MFRA), resulting in a regulatory patchwork. Fishers exploit these inconsistencies—for example, landing juvenile fish legally in one state that are protected in another. This undermines conservation and facilitates laundering of protected species.

Moreover, the fish-meal and fish-oil (FMFO) industry fuels ecological damage by incentivising bycatch. Much of this low-value catch is processed into meal, mostly for export, depriving domestic consumers and aquaculture of vital nutritional inputs.

Government Initiatives

The Union Budget 2025–26 allocated a record ?2,703.67 crore to the fisheries sector, focusing on the sustainable harnessing of resources from the EEZ and high seas, especially around Lakshadweep and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Key schemes include:

- Pradhan Mantri MatsyaSampada Yojana (PMMSY): Focuses on inland fisheries and aquaculture for food security.

- Blue Revolution Scheme: Enhances productivity in marine and inland fisheries.

- Technological Interventions: Satellite-based vessel tracking, Oceansat for forecasting Potential Fishing Zones (PFZ), and GIS mapping are being deployed.

Path to Sustainability

India’s National Policy on Marine Fisheries (2017) embeds sustainability at its core, promoting measures like:

- 61-day uniform fishing bans during monsoons;

- Prohibitions on harmful methods like pair and bull trawling, and LED light usage;

- Promotion of mariculture, artificial reefs, and sea ranching.

Successful models abroad offer direction. New Zealand’s Quota Management System (QMS) aligns catch limits with stock assessments and uses transferable quotas to regulate fishing. India could pilot such a model for its mechanised fleet.

Domestically, Kerala’s enforcement of a Minimum Legal Size (MLS) for threadfin bream boosted catches by 41% in one season. Scaling such practices nationally can ensure ecological recovery and economic benefits.

Way Forward

India must urgently move towards a unified, science-based regulatory framework, including:

- National MLS norms,

- Gear restrictions to reduce juvenile catch,

- Scientific catch limits,

- Closed seasons aligned with spawning cycles.

Simultaneously, fisher cooperatives must be empowered, FMFO quotas capped, and consumer awareness campaigns launched to encourage demand for legally sized, sustainable seafood.

In conclusion, India stands at a critical juncture. Ignoring overfishing risks deepening poverty and ecological collapse. The solutions—rooted in science, equity, and sustainability—are within reach and must be swiftly implemented to safeguard marine wealth and livelihoods for future generations.

Reducing India's Dependence on Imported Fertilisers

- 27 Feb 2025

Context

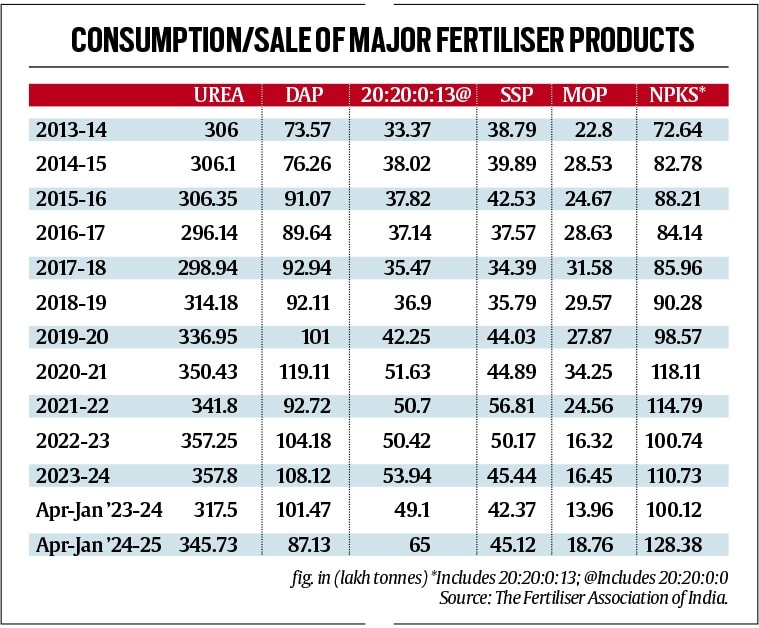

The Indian government is strategizing to cap or reduce the consumption of high-analysis fertilizers—Urea, Di-Ammonium Phosphate (DAP), and Muriate of Potash (MOP)—due to their heavy import dependence, rising economic burden, and adverse environmental impacts. This shift is crucial for ensuring nutrient balance, reducing foreign exchange outflows, and promoting sustainable agriculture.

India’s Dependence on Imported Fertilisers

- MOP: India is fully dependent on imports from countries like Canada, Russia, Jordan, Israel, Turkmenistan, and Belarus, as it has no mineable potash reserves.

- Urea: While over 85% of urea demand is met domestically, production relies on imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Qatar, the US, UAE, and Angola.

- DAP: Imported both as finished fertiliser and raw materials (rock phosphate, sulphur, phosphoric acid, ammonia) mainly from Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Jordan, China, and others.

The Need to Limit High-Analysis Fertiliser Usage

Economic Concerns

- The rupee's depreciation increases fertiliser import costs.

- India spent ?1.75 lakh crore on fertiliser subsidies in 2023-24.

- Subsidised urea is sold at rates far below cost, draining government resources and encouraging overuse.

- DAP's landed price stands at ?55,150 per tonne, with production costs exceeding ?65,000 per tonne, while the government-fixed retail price remains ?27,000 per tonne, necessitating large subsidies.

Environmental Concerns

- Excessive application of urea and DAP depletes organic carbon in soils, reduces microbial diversity, and causes groundwater contamination through nitrate leaching.

- Soil health degradation ultimately reduces crop productivity and ecological resilience.

Governance Challenges

- High subsidies encourage black marketing and non-agricultural diversion.

- Lack of strict nutrient management regulations leads to soil nutrient imbalances.

The Shift Towards Balanced Fertilisation

High-analysis fertilisers like urea (46% nitrogen), DAP (46% phosphorus + 18% nitrogen), and MOP (60% potash) often lead to over-application and inefficiency. Crops instead require a balanced supply of:

- Macronutrients (N, P, K),

- Secondary nutrients (sulphur, calcium, magnesium),

- Micronutrients (zinc, iron, copper, boron, manganese, molybdenum).

Balanced fertilisation ensures efficient nutrient uptake, enhances yields, preserves soil health, and optimises resource use.

Emerging Alternatives

Ammonium Phosphate Sulphate (APS – 20:20:0:13)

- Contains 20% N, 20% P, and 13% S, but no K.

- Sulphur-rich, making it ideal for oilseeds, pulses, maize, cotton, onion, and chilli.

- APS manufacturing is more economical, requiring less costly phosphoric acid compared to DAP.

- Sales surged 32.4%, from 4.9 million tonnes (2022-23) to 6.5 million tonnes (2023-24), making APS the third-most consumed fertiliser after urea and DAP.

- Leading APS producers include Coromandel International, Paradeep Phosphates, and Mangalore Chemicals & Fertilizers.

Single Super Phosphate (SSP – 16% P, 11% S)

- A low-cost, sulphur-rich fertiliser ideal for oilseeds and vegetable cultivation.

Nano Urea and Nano DAP

- Developed by Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative (IFFCO).

- Enhance nutrient use efficiency by 15–20%, require lower application rates, and reduce overall fertiliser consumption.

NPKS Complex Fertilisers

- Formulations like 10:26:26:0, 12:32:16:0, 15:15:15:0, and 14:35:14:0 provide balanced nutrients.

- Help integrate potash application into complexes, reducing direct MOP use.

- NPKS fertiliser sales are projected to reach 14 million tonnes in 2024-25, up from 7.3 million tonnes in 2013-14.

Biofertilisers and Organic Manure

- Promote sustainable farming by improving soil health and reducing chemical fertiliser dependence.

- Supported by government initiatives like the PM-PRANAM scheme.

Effectiveness of Substitutes

- Reduces Import Costs: APS and Nano Urea reduce foreign exchange outflows.

- Enhances Soil Health: Balanced fertilisers prevent soil degradation and restore fertility.

- Improves Crop Yields: Trials demonstrate better nutrient absorption and yield improvements.

- Promotes Sustainability: Encourages ecological farming practices.

Policy Support and The Way Forward

Government Initiatives

- PM-PRANAM Scheme: Promotes alternative fertilisers.

- Nutrient-Based Subsidy (NBS): Encourages balanced fertiliser use.

- Soil Health Card Campaign: Educates farmers about soil-specific nutrient needs.

Strategic Recommendations

- Subsidy Reforms: Focus subsidies on APS, Nano Urea, and complex fertilisers rather than high-analysis fertilisers.

- Technology Adoption: Use AI-based tools like Microsoft FarmVibes AI for precision fertiliser application.

- Domestic R&D Investment: Strengthen indigenous production of fertilisers and biofertilisers.

- Policy Alignment: Integrate fertiliser policy with climate change and agricultural sustainability strategies.

Conclusion

India’s high dependence on imported urea, DAP, and MOP is economically unsustainable and environmentally detrimental. Transitioning towards balanced fertilisers like APS, Nano Urea, and organic alternatives is critical for ensuring long-term agricultural sustainability, reducing subsidy burdens, conserving foreign exchange, and preserving soil health. This shift requires concerted efforts through government policy, farmer education, and technological innovation.

Why Farmers Deserve Price Security

- 11 Jan 2025

Introduction:

The future of Indian agriculture is at a crossroads. With the shrinking of the agricultural workforce and the diversion of fertile farmlands for urbanization, ensuring the sustainability of farming is a strategic imperative. Among the various support mechanisms for farmers, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) remains a central point of debate. Should there be a legal guarantee for MSP? This question has gained prominence, especially with the rising challenges in agriculture, from unpredictable climate patterns to volatile market prices.

The Decline of Agriculture and Its Impact

India’s agricultural sector faces a dual crisis: loss of both land and human resources. Prime agricultural lands across river basins, such as the Ganga-Yamuna Doab or the Krishna-Godavari delta, are being repurposed for real estate, infrastructure, and industrial projects. Additionally, the number of "serious farmers" – those deriving at least half of their income from agriculture – is dwindling. The number of operational holdings may be 146.5 million, but only a small fraction of these farmers remains committed to agriculture.

This decline threatens the future of India’s food security, as the country will need to feed a population of 1.7 billion by the 2060s. To sustain farming and ensure long-term food security, we must secure farmers' livelihoods. Price security, particularly through MSP, plays a crucial role in this context.

The Role of MSP in Securing Farmers

MSP is the government-mandated price at which it guarantees the purchase of crops if market prices fall below a certain threshold. It provides a safety net for farmers against price volatility. The process of fixing MSP involves recommendations by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), which takes into account factors such as the cost of production and market trends. Once approved by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA), MSP is set for various crops, including rice, wheat, and sugarcane.

For farmers to stay in business, there must be a balance between production costs and returns. Farming is a risky business – yield losses can occur due to weather anomalies, pest attacks, or other natural factors. However, price risks can be mitigated with a guaranteed MSP. This would encourage farmers to invest in their land and adopt modern farming technologies, which would boost productivity and reduce costs.

Arguments for and Against Legal MSP Guarantee

Supporters of a legal MSP guarantee argue that it would provide financial security to farmers, protecting them from unpredictable market conditions. It would also promote crop diversification, encourage farmers to shift from water-intensive crops to those less dependent on irrigation, and inject resources into rural economies, thus addressing distress in rural areas.

However, critics highlight several challenges with a legal guarantee for MSP. The most significant concern is the fiscal burden it would impose on the government, potentially reaching Rs. 5 trillion. Furthermore, such a system could distort market dynamics, discouraging private traders and leading to a situation where the government becomes the primary buyer of agricultural produce. This could be economically unsustainable, especially for crops with low yields. Additionally, legal MSP guarantees could violate World Trade Organization (WTO) subsidy principles, adversely impacting India’s agricultural exports.

The Way Forward: A Balanced Approach

Given the challenges associated with a legal MSP guarantee, alternative measures should be explored. Price Deficiency Payment (PDP) schemes, such as those implemented in Madhya Pradesh and Haryana, could be expanded at the national level. These schemes compensate farmers for the difference between market prices and MSP, ensuring price security without the fiscal burden of procurement.

Additionally, the government can focus on improving agricultural infrastructure, such as cold storage facilities, to help farmers better access markets and increase price realization. Supporting Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) could also help farmers by enhancing collective bargaining power and ensuring better prices for their produce. Moreover, gradual expansion of MSP coverage to include a wider range of crops would encourage diversification, reducing the dominance of rice and wheat.

Government Extends Special Subsidy on DAP

- 03 Jan 2025

In News:

The Indian government has decided to extend the special subsidy on Di-Ammonium Phosphate (DAP) fertilizer for another year, a decision aimed at stabilizing farmgate prices and addressing the challenges posed by the depreciation of the Indian rupee.

Key Government Decision

- Extension of Subsidy: The Centre has extended the Rs 3,500 per tonne special subsidy on DAP from January 1, 2025 to December 31, 2025.

- Objective: This extension aims to contain farmgate price surges of DAP, India’s second most-consumed fertilizer, which is being impacted by the fall in the rupee's value against the US dollar.

Fertilizer Price Dynamics and Impact

- MRP Caps on Fertilizers: Despite the decontrol of non-urea fertilizers, the government has frozen the maximum retail price (MRP) for these products.

- Current MRPs:

- DAP: Rs 1,350 per 50-kg bag

- Complex fertilizers: Rs 1,300 to Rs 1,600 per 50-kg bag depending on composition.

- Current MRPs:

- Subsidy on DAP: The subsidy includes Rs 21,911 per tonne on DAP, plus the Rs 3,500 one-time special package.

- Impact of Currency Depreciation:

- The rupee's depreciation has made imported fertilizers significantly more expensive.

- The landed price of DAP has increased from Rs 52,960 per tonne to Rs 54,160 due to the rupee falling from Rs 83.8 to Rs 85.7 against the dollar.

- Including additional costs (customs, port handling, insurance, etc.), the total cost of imported DAP is now Rs 65,000 per tonne, making imports unviable without further subsidy or MRP adjustments.

- The rupee's depreciation has made imported fertilizers significantly more expensive.

Industry Concerns and Viability Issues

- Import Viability:

- Fertilizer companies face significant cost pressures due to rising import prices and the current MRP caps.

- Without an increase in government subsidies or approval to revise MRPs upwards, imports will be unviable.

- Even with the extended subsidy, companies estimate a Rs 1,500 per tonne shortfall due to currency depreciation.

- Stock Levels and Supply Challenges:

- Current stock levels for DAP (9.2 lakh tonnes) and complex fertilizers (23.7 lakh tonnes) are below last year's levels.

- With inadequate imports, there are concerns about fertilizer supply for the upcoming kharif season (June-July 2025).

Government’s Strategy and Fiscal Implications

- Compensation for Imports:

- In September 2024, the government approved compensation for DAP imports above a benchmark price of $559.71 per tonne, based on an exchange rate of Rs 83.23 to the dollar.

- With the rupee falling below Rs 85.7, these previous compensation calculations have become outdated.

- Fiscal Impact:

- The extended subsidy will cost the government an additional Rs 6,475 crore. Despite this, political implications of raising the MRP are minimal, as only non-major agricultural states are facing elections in 2025.

Future Outlook and Priorities

- Immediate Priority: The government’s primary concern is securing adequate fertilizer stocks for the kharif season, focusing on ensuring sufficient imports of both finished fertilizers and raw materials.

- Balancing Factors: The government will need to navigate the complex balance of maintaining fertilizer affordability for farmers, ensuring the viability of fertilizer companies, and managing fiscal constraints.

As the subsidy extension is implemented, all eyes will be on the government's ability to ensure a stable supply of fertilizers while safeguarding both farmer interests and economic sustainability in the face of an increasingly challenging exchange rate environment.

Sustainable Groundwater Management in India’s Agriculture

- 30 Dec 2024

Introduction: Groundwater Crisis and Agriculture

- India's Agricultural Dependence on Groundwater: India is a leading producer of water-intensive crops like rice, wheat, and pulses. The country’s agricultural sector heavily depends on groundwater for irrigation, especially for paddy cultivation.

- Over-exploitation of Groundwater: Groundwater extraction for irrigation is increasingly unsustainable, threatening agricultural sustainability in the long term.

Rising Groundwater Usage and Its Implications

- Population Growth and Groundwater Use: Between 2016 and 2024, global population grew from 7.56 billion to 8.2 billion, and India’s population rose from 1.29 billion to 1.45 billion. Concurrently, groundwater used for irrigation increased from 38% in 2016-17 to 52% in 2023-24, exacerbating the water crisis.

- Over-extraction in Major Paddy-Producing States: States like Rajasthan, Punjab, and Haryana have witnessed severe over-exploitation of groundwater for irrigation.

- Rajasthan: Highest groundwater salinisation (22%) despite receiving the highest average rainfall (608 mm) among these states.

- Punjab and Haryana: Lesser groundwater salinity due to canal irrigation and micro-irrigation systems.

Impact of Excessive Fertilizer Use on Groundwater Quality

- Soil Salinity and Groundwater Contamination: Excessive use of fertilizers, particularly for paddy cultivation, increases soil salinity and contributes to groundwater contamination.

- Toxic Chemicals in Groundwater: Nitrate contamination, caused by nitrogen-based fertilizers, and uranium contamination due to phosphate fertilizers are key concerns in states like Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu.

- Health Risks: Contaminated groundwater poses health risks such as thyroid disorders, cancer, and dental fluorosis, along with reduced agricultural productivity.

Projected Impact on Future Groundwater Availability

- Unsustainable Groundwater Levels: The Central Groundwater Board (CGWB) reports that if current practices continue, over half of the districts in Punjab could face groundwater depletion. Similarly, 21-23% of districts in Haryana and Rajasthan may experience a similar crisis.

- Population Growth and Water Scarcity: With India’s population expected to reach 1.52 billion by 2036, the need for sustainable groundwater management becomes even more critical.

Government Initiatives for Groundwater Management

- National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (2014): Promotes sustainable practices like zero tillage, cover cropping, and micro-irrigation for efficient water and chemical use.

- Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana (2015): Aims to boost irrigation efficiency through drip and sprinkler irrigation methods.

- Atal Bhujal Yojana (2019): Targets efficient groundwater management in water-stressed states like Gujarat, Haryana, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh.

- Success of Government Initiatives: CGWB data shows that the percentage of districts with unsustainable groundwater levels dropped from 23% in 2016-17 to 19% in 2023-24.

Role of State Governments in Groundwater Management

- State-Level Initiatives: States with unsustainable groundwater levels must take proactive measures to manage water resources efficiently.

- Example - Odisha: Odisha's Integrated Irrigation Project for Climate Resilient Agriculture emphasizes irrigation efficiency and climate-smart practices, supported by World Bank funding.

- Encouraging Resource-Efficient Agriculture: States with safe groundwater levels, like Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Telangana, and Odisha, should adopt water-efficient practices to protect groundwater resources.

Conclusion: Ensuring Agricultural Sustainability and Water Security

- Need for Urgent Action: Scaling up efforts to improve irrigation practices and groundwater management is crucial to securing India’s agricultural future.

- Global Food Security: Protecting groundwater resources will not only ensure water security within India but also contribute to global food security amid climate challenges.

- Blueprint for Sustainable Agriculture: States like Odisha are providing a model for sustainable water management, which can be replicated across water-stressed regions in India.

Agrarian Crisis in India

- 15 Dec 2024

Introduction

- Supreme Court Committee Report: A high-level committee, appointed by the Supreme Court in September 2024, submitted its interim report on November 21, 2024, highlighting the severe distress in India's agricultural sector.

- Key Focus Areas:

- Income crisis faced by farmers

- Rising debt burden

- Farmer suicides

- Stagnation in agricultural growth

- Impact of climate change

Key Findings of the Supreme Court Committee Report

Income Crisis in Indian Agriculture

- Daily Earnings: Farmers earn an average of just Rs 27 per day from agricultural activities, a meager income that makes it impossible to sustain a decent standard of living.

- Average Household Income: Agricultural households have an average monthly income of Rs 10,218, far below the basic threshold for a decent life.

Escalating Debt Burden

- Institutional Debt: In 2022-23, Punjab's institutional debt was Rs 73,673 crore, and Haryana's was Rs 76,630 crore.

- Non-Institutional Debt: This burden is further exacerbated by non-institutional debt, contributing 21.3% of total debt in Punjab and 32% in Haryana.

Farmer Suicides

- High Suicide Rates: Over 400,000 farmers and agricultural workers have committed suicide since 1995, primarily due to escalating debt and financial despair.

- Survey Findings: In Punjab, a survey found 16,606 suicides among farmers and farm workers between 2000 and 2015.

Stagnation in Agricultural Growth

- Growth Rates: Between 2014-15 to 2022-23, Punjab's agricultural growth was a mere 2% per year, and Haryana’s was 3.38%, far below the national average.

Disproportionate Employment

- Workforce Participation: 46% of India’s workforce is employed in agriculture, but it contributes only 15% to national income. Many farmers face disguised unemployment and underemployment.

Impact of Climate Change

- Environmental Degradation: Climate change, water depletion, erratic rainfall, and soil degradation are further destabilizing the agricultural sector and threatening food security.

Challenges Faced by the Agricultural Sector

1. Limited Access to Credit and Finance

- Small Farmers: 86% of Indian farmers are small and marginal, struggling to access institutional credit, which limits their ability to invest in modern agricultural inputs.

2. Fragmented Landholdings

- Small Landholdings: The average landholding is 1.08 hectares, insufficient for large-scale, efficient farming, limiting the adoption of modern agricultural techniques.

3. Outdated Farming Practices

- Traditional Methods: Many farmers continue using traditional, inefficient farming practices due to limited access to modern technology.

4. Water Scarcity and Irrigation Issues

- Dependence on Monsoons: 60% of cropped area is rainfed, and only 52% of gross sown area is irrigated, exacerbating vulnerability to droughts and erratic rainfall.

5. Soil Degradation and Erosion

- Degraded Land: 30% of India's agricultural land is affected by soil degradation, leading to lower productivity and reduced resilience to pests.

6. Inadequate Agricultural Infrastructure

- Post-Harvest Losses: Insufficient storage, cold chain, and rural infrastructure result in 15-20% post-harvest losses, further reducing farmers' income.

Government Schemes for Farmers' Welfare

- PM Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana: Direct income support for farmers.

- PM Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY): Crop insurance scheme.

- PM Krishi Sinchai Yojana (PMKSY): Irrigation schemes to enhance water availability.

- e-NAM: National electronic market for better price realization.

- Agriculture Infrastructure Fund: Financial support for infrastructure development.

- Promotion of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs): Empowering farmers through collective marketing and production.

Recommendations for Addressing the Crisis

1. Loan Waivers and Debt Relief

- Debt Alleviation: Immediate measures to reduce the crushing debt burden through loan waivers, a key factor behind farmer suicides.

2. Legal Recognition of Minimum Support Price (MSP)

- MSP Protection: Granting legal backing to MSP to ensure farmers receive a fair price for their produce, reducing price volatility and income insecurity.

3. Promotion of Sustainable Farming

- Organic Farming: Encouraging organic farming and crop diversification to improve soil health and reduce dependency on a few staple crops.

- Climate-Resilient Agriculture: Adopting water-efficient practices, drought-resistant crops, and sustainable farming techniques.

4. Agricultural Marketing Reforms

- Market Efficiency: Improving the agricultural marketing system by establishing farmer-friendly markets and reducing intermediaries to ensure better price realization.

5. Rural Employment Generation

- Diversification: Creating non-agricultural employment opportunities in rural areas through skill development and promoting agro-based industries.

6. Climate Adaptation Measures

- Water Management: Enhancing water management systems and promoting rainwater harvesting.

- Resilience to Climate Change: Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure and farming technologies.

Implications of the Findings

Economic Impact

- Agricultural Decline: Continued neglect of the agricultural sector poses a risk to India's economy, potentially leading to long-term economic instability and increased rural-urban migration.

Food Security

- Threat to National Food Security: Declining agricultural productivity, exacerbated by climate change and inadequate reforms, threatens the country’s ability to meet food demands.

Social Stability

- Farmer Suicides and Unrest: The ongoing crisis, marked by widespread suicides and growing despair, risks social instability and unrest, particularly in rural regions.

Conclusion: Urgent Need for Reform

The committee’s report underscores the critical need for comprehensive reforms in India’s agricultural sector to alleviate the crisis. Immediate action is required to address the debt burden, improve incomes, and ensure sustainable agricultural practices. Legal reforms like MSP recognition and debt relief, along with investments in infrastructure and climate resilience, are key to securing a stable future for Indian agriculture.

National Mission on Natural Farming (NMNF)

- 29 Nov 2024

In News:

The Union Cabinet recently approved the launch of the National Mission on Natural Farming (NMNF), marking a significant shift in the government's approach to agriculture. This initiative, a standalone Centrally Sponsored Scheme under the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers' Welfare, aims to promote natural farming across India, focusing on reducing dependence on chemical fertilizers and promoting environmentally sustainable practices.

What is Natural Farming?

Natural farming, as defined by the Ministry of Agriculture, is a chemical-free agricultural method that relies on inputs derived from livestock and plant resources. The goal is to encourage farmers to adopt practices that rejuvenate soil health, improve water use efficiency, and enhance biodiversity, while reducing the harmful effects of fertilizers and pesticides on human health and the environment. The NMNF will initially target regions with high fertilizer consumption, focusing on areas where the need for sustainable farming practices is most urgent.

Evolution of Natural Farming Initiatives

The NMNF is not an entirely new concept but a scaled-up version of the Bhartiya Prakritik Krishi Paddhti (BPKP) introduced during the NDA government's second term (2019-24). The BPKP was part of the larger Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojna (PKVY) umbrella scheme, and natural farming was also promoted along the Ganga River under the NamamiGange initiative in 2022-23. With the renewed focus on natural farming following the 2024 elections, the government aims to extend the lessons learned from BPKP into a comprehensive mission mode, setting a clear direction for sustainable agriculture.

In Budget speech for 2024-25, it was announced a plan to initiate one crore farmers into natural farming over the next two years. The mission will be implemented through scientific institutions and willing gram panchayats, with the establishment of 10,000 bio-input resource centers (BRCs) to ensure easy access to the necessary inputs for natural farming.

Key Objectives

The NMNF aims to bring about a paradigm shift in agricultural practices by:

- Expanding Coverage: The mission plans to bring an additional 7.5 lakh hectares of land under natural farming within the next two years. This will be achieved through the establishment of 15,000 clusters in gram panchayats, benefiting 1 crore farmers.

- Training and Awareness: The mission will establish around 2,000 model demonstration farms at Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs), Agricultural Universities (AUs), and farmers' fields. These farms will serve as hubs for training farmers in natural farming techniques and input preparation, such as Jeevamrit and Beejamrit, using locally available resources.

- Incentivizing Local Inputs: The creation of 10,000 bio-input resource centers will provide farmers with easy access to bio-fertilizers and other natural farming inputs. The mission emphasizes the use of locally sourced inputs to reduce costs and improve the sustainability of farming practices.

- Farmer Empowerment: 30,000 Krishi Sakhis (community resource persons) will be deployed to assist in mobilizing and guiding farmers. These trained individuals will play a key role in generating awareness and providing on-ground support to the farmers practicing natural farming.

- Certifications and Branding: A major aspect of the mission is to establish scientific standards for natural farming produce, along with a national certification system. This will help in creating a market for organically grown produce and encourage more farmers to adopt sustainable practices.

Targeting High Fertilizer Consumption Areas

The Ministry of Agriculture has identified 228 districts in 16 states, including Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Maharashtra, and West Bengal, where fertilizer consumption is above the national average. These districts will be prioritized for the NMNF rollout, as they have high fertilizer usage but low adoption of natural farming practices. By focusing on these areas, the mission seeks to reduce the over-dependence on chemical fertilizers and foster a transition to more sustainable farming practices.

Benefits of Natural Farming

The NMNF aims to deliver multiple benefits to farmers and the environment:

- Cost Reduction: Natural farming practices can significantly reduce input costs by decreasing the need for costly chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

- Soil Health and Fertility: By rejuvenating the soil through organic inputs, natural farming improves soil structure, fertility, and microbial activity, leading to long-term agricultural sustainability.

- Climate Resilience: Natural farming enhances resilience to climate-induced challenges such as drought, floods, and waterlogging.

- Healthier Produce: Reduced use of chemicals results in safer, healthier food, benefitting both farmers and consumers.

- Environmental Conservation: The promotion of biodiversity, water conservation, and carbon sequestration in soil leads to a healthier environment for future generations.

Conclusion

The launch of the National Mission on Natural Farming represents a critical step toward transforming India's agricultural practices into a more sustainable and environmentally friendly model. By targeting regions with high fertilizer usage, providing farmers with the tools and knowledge for natural farming, and creating a system for certification and branding, the government hopes to make natural farming a mainstream practice. As India continues to grapple with the challenges of climate change, soil degradation, and health risks from chemical inputs, the NMNF provides a promising framework for sustainable agriculture that benefits farmers, consumers, and the environment alike.

India’s Agricultural Sector

- 23 Nov 2024

In News:

India’s agricultural sector, which employs 42.3% of the population, is crucial to the nation’s economy. However, it faces a range of challenges that need to be addressed to ensure long-term stability, food security, and sustainable growth.

Current Performance of India’s Agricultural Sector

- Key Agricultural Metrics and Growth

- Foodgrain Production: India produced 330.5 million metric tonnes (MT) of foodgrains in 2022-23, maintaining its position as the world’s second-largest producer.

- Horticulture Production: A record high of 351.92 million tonnes in horticultural production was achieved, marking a 1.37% increase from the previous year.

- Market Outlook

- India’s agricultural market is projected to reach USD 24 billion by 2025.

- The food and grocery retail sector is ranked as the sixth-largest globally, with 70% of its sales generated from retail.

- Investment and Export Trends

- FDI in Agriculture: From April 2000 to March 2024, the agricultural services sector attracted USD 3.08 billion in foreign direct investment, while the food processing industry garnered USD 12.58 billion.

- Agricultural Exports: India’s agricultural and processed food exports reached USD 4.34 billion in 2024-25, including products like marine products, rice, and spices.

Key Challenges Confronting India’s Agriculture

- Climate Change and Environmental Impact:Extreme weather events, such as heatwaves and erratic rainfall, continue to impact agricultural productivity. In 2023, India experienced its second-warmest year on record, contributing to crop damage and rising food prices.

- Water Stress and Irrigation Inefficiency: Agriculture consumes the majority of India’s water resources, but irrigation efficiency is still low. The country relies heavily on flood irrigation, which leads to significant water wastage. Only 11% of agricultural land is under micro-irrigation, far below global standards.

- Land Fragmentation and Declining Farm Sizes: The average size of agricultural farms has decreased from 1.08 hectares in 2016-17 to 0.74 hectares in 2021-22, hindering the adoption of modern farming practices and mechanization.

- Market Access and Price Realization: Farmers continue to face challenges in accessing fair market prices due to the dominance of intermediaries and inadequate market infrastructure. Despite reforms like e-NAM, price gaps between farm-gate and retail prices persist, leaving farmers with a smaller share of the final price.

- Technology Adoption and Digital Divide: Although agritech is growing in India, only 30% of farmers use digital tools in agriculture, and rural digital literacy is just 25%, which limits the widespread adoption of modern farming solutions.

Addressing Structural Issues in Indian Agriculture

- Soil Health and Sustainability:The excessive use of chemical fertilizers and mono-cropping practices has led to soil degradation. Approximately 30% of agricultural land in India is experiencing degradation, impacting productivity and sustainability. Stubble burning further exacerbates this issue, worsening air quality and soil health.

- Crop Diversification Challenges:Many farmers are locked into the wheat-rice cycle due to Minimum Support Price (MSP) guarantees, limiting the cultivation of other crops like pulses and oilseeds. Although India is the largest producer of pulses, the domestic production is insufficient to meet the growing demand.

- Feminisation of Agriculture:Women make up 63% of agricultural workers but own only 11-13% of the operational land, limiting their access to resources and decision-making power. This gender disparity hampers their economic security and limits their participation in agricultural development.

Conclusion

India’s agricultural sector holds immense potential but is facing significant structural challenges that must be addressed to ensure its long-term growth and sustainability. Urgent reforms are needed to address issues like climate vulnerability, inefficient irrigation, land fragmentation, and limited market access. Additionally, fostering technology adoption, improving infrastructure, and addressing gender disparities will be crucial for improving the sector's performance and securing India’s food security needs.

National Agriculture Code (NAC)

- 07 Oct 2024

Introduction

The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) is in the process of developing the National Agriculture Code (NAC), which aims to establish standardized practices across the agricultural sector. This initiative mirrors existing frameworks such as the National Building Code and the National Electrical Code.

Purpose of the National Agriculture Code

The NAC seeks to standardize agricultural practices throughout the entire agricultural cycle, ensuring consistency and quality in farming operations. It will serve as a comprehensive guide for farmers, agricultural institutions, and policymakers.

Structure of the NAC

The NAC will be divided into two main parts:

- General Principles: Applicable to all crops, providing a foundational framework.

- Crop-Specific Standards: Tailored standards for key crops such as paddy, wheat, oilseeds, and pulses.

Coverage of the NAC

The code will encompass a wide range of agricultural processes, including:

- Agricultural Cycle: From crop selection to post-harvest operations.

- Post-Harvest Operations: Including standards for storage, processing, and traceability.

- Emerging Practices: Guidelines for natural and organic farming, as well as the integration of Internet-of-Things (IoT) technologies.

- Input Management: Recommendations for the use of fertilizers, pesticides, and weedicides.

Objectives of the National Agriculture Code

The BIS outlines several key objectives for the NAC:

- Standardization: Create a national code that reflects the diverse agro-climatic zones and socio-economic conditions across India.

- Quality Culture: Act as a reference for policymakers and regulators to enhance agricultural quality.

- Guidance for Farmers: Provide a practical guide to assist farmers in making informed decisions.

- Integration of Standards: Combine existing Indian standards with agricultural practices.

- Modernization: Emphasize aspects such as SMART farming, sustainability, and documentation.

- Capacity Building: Support training programs conducted by agricultural extension services.

Implementation Timeline

The BIS has established working panels comprising university professors and research organizations to draft the NAC, with a target completion date set for October 2025. Following this, training programs for farmers will be organized, facilitated by universities with financial assistance from the BIS.

Standardized Agriculture Demonstration Farms (SADF)

In conjunction with the NAC, the BIS is launching Standardized Agriculture Demonstration Farms (SADFs) at select agricultural institutions. These farms will serve as experimental sites to test and implement agricultural practices aligned with Indian standards. Partnerships with prominent agricultural institutes are being formalized through Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs), with two agreements already signed, including one with Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture and Technology.

Significance of the NAC

- Uniform Standards: Promotes best practices in diverse agricultural environments.

- Stakeholder Guidance: Provides a structured framework for informed decision-making.

- Support for Modern Techniques: Encourages the adoption of innovative practices and technologies.

- Farmer Empowerment: Facilitates training and capacity building for enhanced productivity.

Challenges and Limitations

- Implementation Barriers: Standardizing practices across varied climates and soil conditions may prove challenging.

- Adoption Resistance: Smaller farmers might struggle with resource availability or awareness of new practices.

- Dynamic Agricultural Needs: The need for frequent updates to the NAC to keep pace with evolving agricultural trends.

- Infrastructure Constraints: Rural areas may lack the necessary infrastructure to effectively implement NAC guidelines.

Conclusion

The National Agriculture Code represents a pivotal move towards modernizing and standardizing agricultural practices in India. While it aims to enhance productivity and sustainability, its success hinges on effective implementation, farmer engagement, and ongoing updates to meet the changing landscape of agriculture.

Drone Technology in Agriculture

- 02 Sep 2024

In News:

Farmers in Bhagthala Khurd, Kapurthala, and Amritsar are increasingly using drones to apply pesticides to their maize and moong crops. Drones, also known as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), are advanced flying machines that can be operated either autonomously or via remote control.

Drone Technology in Agriculture

While the use of drones in Indian agriculture is still emerging, it shows great potential. In Punjab, 93 out of the 100 drones provided to farmers by the Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative (IFFCO) under the Centre’s ‘NAMO Drone Didi’ scheme are already in operation. Each drone, costing Rs 16 lakh, is equipped with a 12-litre water tank.

Benefits

- Health Protection: Drones minimize farmers' direct exposure to harmful pesticides, reducing the risk of health issues like cancer and kidney problems.

- Efficiency: Drones can spray an acre in just 5-7 minutes, significantly faster than the several hours required for manual application. They ensure a uniform application, which can enhance crop yields.

- Data Collection: Drone data helps pinpoint areas requiring attention, leading to better crop management and increased profits.

- Nano Fertilisers: Drones effectively handle nano fertilisers, ensuring even distribution of these small quantities that are difficult to spread manually.

- Pest Control: Drones enable timely application of pesticides during infestations of pests such as pink bollworms, locusts, and whiteflies.

- Environmental Benefits: Drones improve nutrient absorption from nano fertilisers by up to 90%, reducing runoff and pollution. Leaf-based application is also less polluting than soil-based methods.

- Water Conservation: Drones reduce water usage by up to 90% compared to traditional methods.

- Cost Reduction: They decrease the need for manual labor and reduce pesticide and chemical use, lowering overall costs.

- Additional Uses: Drones are also used to drop seed balls (a mix of soil and cow dung with seeds) for potential reforestation projects.

Challenges

- Job Loss: The use of drones may reduce demand for manual labor, affecting job opportunities for laborers.

- Knowledge and Training: Farmers may lack the necessary skills and training to operate drones effectively.

- Cost: The high cost of drones can be a significant barrier for many farmers.

- Regulatory Barriers: Regulatory challenges may complicate the adoption of drones in agriculture.

Initiatives

- Digital India Campaign: Aims to enhance digital infrastructure and provide training.

- Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR): Promotes precision agriculture technologies, including drones.

- Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme: Offers Rs. 120 crore (US$ 14.39 million) to incentivize domestic drone manufacturing and reduce import reliance.

- Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanization (SMAM): Provides financial aid to farmers purchasing drones, making technology more accessible.

- NAMO Drone Didi Scheme: Launched to empower women Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and provide access to modern agricultural technology.

- Support and Training: Efforts are underway to offer training and support to farmers to overcome adoption barriers.

Conclusion and Way Forward

Drone technology holds the promise of transforming agriculture by boosting efficiency, yields, and cost-effectiveness. In Punjab, where traditional manual methods have prevailed, drones offer a new approach to pesticide and fertiliser application. It is essential for farmers and policymakers to work together to address challenges and ensure that the benefits of drones are fully realized while mitigating any potential drawbacks.

The role of district agro-met offices in supporting farmers

- 10 Sep 2024

In News:

- Last week, PTI reported that the India Meteorological Department (IMD) is planning to revive District Agro-Meteorology Units (DAMUs) under the Gramin Krishi Mausam Sewa (GKMS) scheme.

Background:

- The IMD established 199 DAMUs in 2018 in collaboration with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

- The aim was to use weather data to prepare and disseminate sub-district level agricultural advisories. In March, DAMUs were shut down following an order issued by the IMD.

Why are agro-met units important?

- Around 80% of farmers in India are small and marginal. They largely practise rain-fed agriculture in the backdrop of a decades-long farm crisis that is now overlaid with climate change-related weather variability.

- The DAMUs were located within Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs). Scientists and researchers trained in meteorology and agriculture were recruited as DAMU staff. They used weather data provided by the IMD like rainfall, temperature and wind speeds to prepare agricultural advisories related to sowing and harvesting, usage of fertilizers and pesticides, irrigation etc.

- These advisories were sent to millions of farmers across the country free-of-cost in local languages twice a week. They were shared via text messages, WhatsApp groups, newspapers and also through in-person communication from DAMU staff and KVK officers.

- Since these advisories provided weather information in advance, they helped farmers plan activities like irrigation. They also served as early warnings for extreme events like droughts and heavy rainfall. Many studies conducted over the years have stressed the benefits of agro-met advisories.

Why were DAMUs shut down?

- According to an Article-14 report, the NITI Aayog misrepresented the role of District Agricultural Management Units (DAMUs) and advocated for their privatization. The report claims that NITI Aayog inaccurately stated that agro-met data was automated, thereby diminishing the role of DAMU staff. In reality, DAMU staff were crucial in creating agricultural advisories based on IMD weather data, which were disseminated to farmers in local languages. NITI Aayog also proposed monetizing these services, contrasting with the current free provision of agro-met information to all farmers.

- A policy brief from the National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bangalore, released in August, highlights that localized and accessible advisories from District Agricultural Management Units (DAMUs) have significantly improved farmers' responses to climatic variations in the Kalyana-Karnataka region. This has led to increased yields and incomes. The brief recommends reconsidering the decision to discontinue DAMUs and suggests exploring ways to enhance their effectiveness and presence.

What about private players?

Currently, a few private companies offer weather advisories, but their services are often too costly for small and marginal farmers. Dr. M. N. Thimmegowda, a professor at the University of Agricultural Sciences noted that annual subscriptions can cost ?10,000 per crop, leading to expenses of ?20,000-40,000 for vegetable and cereal growers, and up to ?60,000-80,000 for specialized advisories. Additionally, there is concern that these companies may provide biased recommendations for fertilizers and pesticides, favoring certain brands.

Need for a Farmer-Friendly Agri-Export Policy

- 14 May 2024

Why is it in the News?

The current government policy, skewed towards consumers, unfavourably impacts farmers, necessitating a shift to enhance farmers' incomes.

Current State of India‘s Agricultural Exports: