Passive Euthanasia in India

- 30 Nov 2025

In News:

In a recent case, the Supreme Court directed the District Hospital, Noida, to constitute a Primary Medical Board to examine whether life-sustaining treatment can be withdrawn for a 32-year-old man in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) for over 12 years. The petition, filed by the patient’s father, sought passive euthanasia, not active intervention. The Court, while acknowledging the patient’s irreversible condition and total disability, reaffirmed that any decision must strictly follow the safeguards laid down in its earlier judgments, and sought a medical report within two weeks before taking a final call.

Understanding Euthanasia and Persistent Vegetative State

A Persistent Vegetative State (PVS) is a condition where higher brain functions such as awareness and cognition are irreversibly lost, while basic functions like breathing, circulation and reflexes continue.

Euthanasia refers to intentionally accelerating death to relieve suffering from an incurable condition and is broadly of two types:

- Active Euthanasia: Direct action to end life (illegal in India).

- Passive Euthanasia: Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, allowing natural death.

India permits only passive euthanasia, subject to strict legal and procedural safeguards.

Legal Position in India

Indian law does not recognise an unfettered “right to die” under Article 21, but the Supreme Court has interpreted the right to life to include the right to die with dignity in exceptional circumstances.

- Active euthanasia is prohibited and punishable under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, as culpable homicide or murder.

- Passive euthanasia is legally permissible under judicially evolved safeguards.

Key judicial milestones include:

- Aruna Shanbaug case (2011): Allowed withdrawal of life support for incompetent patients under court supervision.

- Common Cause case (2018): Recognised passive euthanasia and validated advance medical directives (living wills) for competent adults.

- 2023 modifications: Simplified procedures by reducing medical board size and experience requirements, and setting clear timelines to make the process workable.

Procedural Safeguards

The Supreme Court mandates a two-tier medical review:

- Primary Medical Board constituted by the hospital.

- Secondary Medical Board at the district level.

These boards assess the medical condition, irreversibility, and best interests of the patient. Judicial oversight ensures protection against misuse while respecting dignity.

Ethical Dimensions

The euthanasia debate reflects a tension between competing ethical principles:

- Arguments in favour emphasise autonomy, compassion, minimisation of suffering, and rational allocation of scarce medical resources.

- Arguments against stress the sanctity of life, the doctor’s duty of non-maleficence, risks of a slippery slope, and erosion of trust in medical ethics.

India’s approach attempts a middle path rejecting active killing while permitting dignified death in narrowly defined circumstances.

Global Perspective

Countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium permit both euthanasia and assisted suicide under strict laws, while others like Switzerland allow assisted suicide but prohibit active euthanasia. These variations show that euthanasia is shaped as much by societal values as by medical capability.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s direction to constitute a medical board reflects India’s cautious, dignity-centric approach to end-of-life decisions. By balancing compassion with safeguards, autonomy with ethics, and medical judgment with judicial oversight, India seeks to ensure that death, when inevitable, is humane rather than mechanical. As medical technology prolongs biological life, evolving jurisprudence on passive euthanasia will remain crucial to uphold constitutional morality, human dignity and ethical restraint.

Entrepreneur-in-Residence (EIR) Programme

- 29 Nov 2025

In News:

India’s innovation landscape is witnessing a gradual but significant shift from laboratory-bound research to market-oriented problem solving. The Entrepreneur-in-Residence (EIR) Programme, highlighted recently by the Union Minister of State for Science and Technology, has emerged as a critical instrument in this transition. Introduced under the National Initiative for Developing and Harnessing Innovations (NIDHI), the EIR Programme reflects the government’s effort to embed entrepreneurship within the country’s public research ecosystem and nurture a new generation of scientist-entrepreneurs.

The EIR Programme is designed to encourage graduate students and young researchers to pursue entrepreneurship as a viable career option. It provides both financial and non-financial support in the form of a structured fellowship, enabling innovators to work on high-risk, high-impact ideas within recognised incubation environments. Selected fellows receive a monthly financial support of up to ?30,000 for a maximum period of 12 months, allowing them to focus on ideation, validation and early-stage development without immediate financial pressures. Beyond funding, the programme offers access to Technology Business Incubators (TBIs), mentoring, technical guidance, business advisory services and industry linkages.

Implemented by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) in association with the NCL Venture Centre, Pune, the EIR Programme seeks to bridge the long-standing gap between academic research and commercial application. By embedding entrepreneurial pathways within research institutions, it addresses a structural weakness of India’s innovation system, strong scientific output but limited translation into scalable products and enterprises.

The programme’s growing relevance was underscored at the annual meeting of the Biotechnology Research and Innovation Council (BRIC), where it was described as a cornerstone of India’s biotechnology innovation ecosystem. BRIC, established as a unified umbrella for multiple biotechnology research institutes, represents a shift toward collaborative and translational research. Within this framework, the EIR Programme has helped cultivate researchers who combine academic rigour with market awareness, encouraging them not just to discover, but to deliver solutions with societal and economic impact.

A notable strength of the EIR Programme lies in its ability to attract private sector participation and venture capital interest. By de-risking the early stages of innovation through public funding and institutional support, it creates a pipeline of credible startups emerging directly from public R&D institutions. This has particular significance in sectors such as biotechnology, healthcare, agriculture, green energy and industrial biotechnology, where long gestation periods and high uncertainty often deter private investment at the ideation stage.

The programme also aligns with broader policy objecttives. From a Science and Technology perspective, it promotes translational research, patenting and commercialization, areas increasingly emphasised in national innovation strategies. From an economic standpoint, it supports startup creation, job generation and the development of knowledge-intensive enterprises, complementing initiatives aimed at strengthening MSMEs and deep-tech startups. Ethically and socially, it reinforces values of scientific temper, innovation for public good, collaboration and responsible risk-taking.

However, sustaining the programme’s impact will require scaling up support, expanding interdisciplinary participation, and ensuring stronger regional spread beyond major research hubs. Continuous evaluation of outcomes such as startup survival rates, technology adoption and societal impact will be crucial.

In conclusion, the Entrepreneur-in-Residence Programme represents a strategic shift in India’s approach to innovation, moving from isolated research excellence to integrated, market-linked problem solving. By empowering young researchers to become entrepreneurs within the public research system, it strengthens India’s journey toward a resilient, innovation-driven economy and a globally competitive biotechnology ecosystem.

Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Agricultural Transformation

- 28 Nov 2025

In News:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is emerging as a powerful enabler of transformation across agrifood systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where smallholder farmers produce nearly one-third of the world’s food. The World Bank–led report “Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Agricultural Transformation” highlights how AI, if deployed responsibly and inclusively, can enhance productivity, climate resilience, and equity while cautioning that technology alone is insufficient without enabling investments and governance.

AI and the Changing Agrifood Landscape

Recent trends show a decisive shift from isolated digital pilots to systems-level AI adoption across the entire agricultural value chain. Advances in Generative AI and multimodal models combining text, images, satellite data and sensor feeds are enabling natural-language advisories in local languages and predictive insights for farmers. Investments in AI for agriculture are rising rapidly, with the market projected to grow from about US$1.5 billion in 2023 to over US$10 billion by 2032. Importantly, LMIC-focused innovations such as lightweight “small AI” models on smartphones and offline devices are expanding reach in low-connectivity settings.

Opportunities Across the Value Chain

AI applications span crops, livestock, advisory services, markets and finance. In production, AI accelerates research on climate-resilient seeds and breeding, improves pest detection, precision irrigation and nutrient management cutting chemical use significantly while raising yields. In farm management, real-time soil and weather analytics help farmers make data-driven decisions. Market-facing tools enhance price forecasting, traceability and logistics, reducing post-harvest losses and improving transparency. AI also expands inclusive finance through alternative credit scoring and climate-indexed insurance, bringing formal financial services to previously unbanked smallholders. For governments, AI strengthens early-warning systems, yield and price forecasting, and targeted subsidies, improving food security planning.

Emerging Initiatives

Several initiatives demonstrate AI’s promise. International research centres use machine learning and computer vision to speed up phenotyping and genebank screening, multiplying throughput while reducing costs. Data coalitions and agricultural data exchanges in countries like Ethiopia and India are creating shared, sovereign data layers to train local models. Public–private platforms in Africa and India are piloting multilingual AI advisory services, reaching tens of thousands of farmers and showing gains in income, quality and input efficiency.

Key Challenges

Despite its potential, AI adoption faces serious constraints. Digital infrastructure gaps limited broadband, electricity and devices restrict real-time deployment in rural areas. Data scarcity and bias, with training datasets dominated by high-income regions, risk producing irrelevant or exclusionary recommendations. Low digital literacy and trust, especially among women and older farmers, can slow uptake. Weak regulatory frameworks on data ownership, privacy, transparency and liability create uncertainty, while there is a risk that AI may deepen inequalities by favouring large agribusinesses or locking users into proprietary platforms.

Way Forward

To harness AI responsibly, countries must adopt national AI strategies with a clear agricultural focus, aligned to food security, climate adaptation and nutrition goals. Investments in digital public infrastructure and rural connectivity are essential. Building open, interoperable and FAIR data ecosystems through agricultural data exchange nodes will enable context-specific models. Equally important are capacity-building and extension reforms, using local-language, multimodal interfaces. Finally, robust ethical and governance frameworks, developed through participatory processes and regulatory sandboxes, are vital to ensure accountability and inclusion.

Conclusion

AI can significantly boost agricultural productivity, resilience and incomes, but only if embedded within broader reforms in infrastructure, skills, data and governance. Used ethically and inclusively, AI can complement traditional agricultural transformation and support long-term food security and environmental sustainability.

Indian Constitution at 76: Enduring Relevance of a Transformative Charter

- 27 Nov 2025

In News:

As India marks the 76th anniversary of the adoption of the Constitution, it invites renewed reflection on the vision, depth and contemporary relevance of a document that sought to transform a deeply unequal society. Drafted in the aftermath of colonial rule, the Indian Constitution was not merely a legal framework to limit state power; it was a social revolution embedded in constitutional form. Even after seven decades, it continues to outpace many Western constitutional models in its scope, ambition and adaptability.

From its inception, the Indian Constitution was ahead of its time. It adopted universal adult franchise in 1950, at a moment when several established democracies such as the United States and Australia still denied voting rights to large sections of their populations. Unlike liberal constitutions that focused primarily on formal equality, India confronted entrenched social hierarchies, particularly caste, through explicit constitutional provisions. Articles 15(2), 17 and 23 addressed discrimination, untouchability and bonded labour, extending constitutional scrutiny beyond the state to private and social domains. Further, the institutionalisation of affirmative action for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes at the founding stage was a bold acknowledgment that political equality alone could not remedy historical injustice.

In contrast to many Western constitutional models, which largely evolved as instruments to restrain sovereign power, the Indian Constitution functioned as a transformative tool. It recognised that oppression in India often stemmed from society itself—through caste, patriarchy and community dominance—and therefore required group-differentiated protections. Minority cultural and educational rights under Articles 29 and 30, and the integration of Directive Principles of State Policy, reflected a commitment to substantive equality and socio-economic restructuring. While Western democracies incorporated anti-discrimination safeguards largely in the 1960s and 1970s, India embedded them in the original constitutional text through Articles 14 to 17.

The evolution of the Constitution since 1950 has further strengthened its relevance. Judicial interpretation expanded the scope of Article 21 from mere protection of life to a constellation of rights including privacy, education, environment and legal aid. The Basic Structure Doctrine ensured that core constitutional values such as democracy, secularism, federalism and judicial review remain immune from majoritarian alteration. Social justice provisions evolved through reservation reforms, constitutional amendments addressing promotion, economic disadvantage and ongoing debates on sub-categorisation. Federalism too has matured through institutional mechanisms like the GST Council and the emphasis on cooperative federalism after economic liberalisation.

Despite these strengths, the Constitution faces serious contemporary challenges. Caste discrimination, manual scavenging and spatial segregation persist despite constitutional prohibitions. The consolidation of executive power threatens the autonomy of constitutional institutions, while preventive detention and emergency-era provisions continue to confer expansive coercive authority on the state. New-age concerns—digital surveillance, algorithmic governance and inadequate data protection—pose fresh risks to privacy and civil liberties. Additionally, tensions between religious freedom and gender justice, and the rise of majoritarian narratives, test the plural ethos embedded in Articles 25 to 30.

The way forward lies not in constitutional revisionism but in constitutional renewal. Strengthening institutional autonomy through transparent appointments and independent funding, expanding constitutional literacy, updating privacy and data protection laws, and enacting comprehensive anti-discrimination frameworks are imperative. A participatory model of federalism and renewed commitment to minority and cultural rights will be crucial in preserving India’s constitutional balance.

In conclusion, India’s Constitution remains a living, transformative document. Its endurance lies in its capacity to combine liberal freedoms with social justice, and stability with adaptability. As India looks toward 2047, constitutional morality, pluralism and equality must continue to guide national progress.

India–Brazil–South Africa (IBSA) Dialogue Forum

- 26 Nov 2025

In News:

On the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Johannesburg, the leaders of India, Brazil and South Africa reaffirmed the relevance of the IBSA (India–Brazil–South Africa) Dialogue Forum at a time of global fragmentation, geopolitical churn and weakening multilateralism. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for unified action against terrorism, reform of global institutions, and cooperation in climate-resilient agriculture and digital innovation underscored IBSA’s potential as a values-based Global South platform.

What is the IBSA Forum?

IBSA was formalised in 2003 through the Brasilia Declaration as a trilateral grouping of three large democracies from Asia, Africa and South America. It has no permanent secretariat or headquarters, operating through periodic summits, ministerial meetings and working groups.

Three pillars of IBSA cooperation are:

- Political consultation on global and regional issues.

- Trilateral sectoral cooperation through working groups and people-to-people forums.

- Development cooperation via the IBSA Trust Fund, established in 2004 and operational since 2006.

The IBSA Fund has supported around 50 South–South development projects in health, education, women’s empowerment, agriculture and renewable energy across more than 40 developing countries, especially Least Developed Countries (LDCs).

Key Outcomes and Proposals at the 2025 IBSA Meeting

At Johannesburg, India proposed several initiatives to reinvigorate IBSA:

- Unified push against terrorism: Calling for “no double standards,” India proposed institutionalising an NSA-level dialogue for regular security and counter-terrorism coordination.

- UN Security Council Reform: Leaders reiterated that existing global institutions do not reflect contemporary realities. As none of the IBSA countries is a permanent UNSC member, coordinated advocacy for reform was emphasised.

- Climate-Resilient Agriculture Fund: Building on the success of the IBSA Fund, India proposed a dedicated fund to support climate adaptation in agriculture.

- Digital Innovation Alliance: Sharing India’s Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)-such as UPI, CoWIN, cybersecurity frameworks and women-led digital initiatives with other developing countries.

- Maritime and Defence Cooperation: IBSA’s practical security dimension is reflected in IBSAMAR, the trilateral naval exercise, whose 8th edition was held in 2024 off South Africa.

Strategic Importance of IBSA for India

- Voice of the Global South: IBSA allows India to project leadership without the structural dominance of China, unlike platforms such as BRICS or SCO.

- Advancing UNSC Reform: Collective advocacy by three regional powers strengthens India’s long-standing demand for a permanent UNSC seat.

- Soft Power and Development Diplomacy: The IBSA Fund exemplifies non-coercive, transparent South–South cooperation, enhancing India’s credibility as a development partner.

- Exporting Indian Solutions: DPI cooperation enables India to globalise its governance innovations in payments, health and digital inclusion.

Key Challenges

Despite its promise, IBSA faces several constraints:

- Agenda Overlap with BRICS: Many IBSA priorities UN reform, Global South development, climate action are also pursued within BRICS, which attracts greater political attention.

- Geopolitical Divergence: Variations in foreign policy outlooks, especially Brazil’s and South Africa’s relatively flexible stances towards China, limit strategic convergence.

- Low Economic Integration: Intra-IBSA trade remains modest due to weak logistics and similar economic profiles, creating competition rather than complementarity.

- Institutional Weakness: Absence of a permanent secretariat hampers continuity, monitoring and implementation.

Way Forward

To remain relevant, IBSA must:

- Focus on niche areas such as democratic governance, DPI, climate-resilient development and counter-terrorism.

- Establish a small permanent secretariat and an IBSA Business Council for continuity and economic engagement.

- Use IBSA as a coordinating caucus within BRICS to balance great-power dominance.

- Revitalise the IBSA Fund to showcase tangible outcomes of South–South cooperation.

Conclusion

In an era of geopolitical uncertainty and weakening multilateralism, IBSA offers a values-driven, democratic and inclusive alternative for Global South cooperation. If revitalised with focused agendas and stronger institutions, the forum can amplify India’s strategic influence while promoting equitable growth, global governance reform and human-centric development.

India’s Four Labour Codes

- 25 Nov 2025

In News:

India has operationalised the four Labour Codes, the Code on Wages (2019), Industrial Relations Code (2020), Code on Social Security (2020), and Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSH) Code (2020) replacing 29 central labour laws.

Enacted on the recommendations of the Second National Commission on Labour (2002), these reforms aim to modernise labour regulation, simplify compliance, extend social security, and align India’s workforce framework with the needs of a dynamic economy and Aatmanirbhar Bharat.

Key Provisions of the Four Labour Codes

1. Code on Wages, 2019

- Universal Coverage: Applies to all employees across sectors, wages, and gender (including transgender persons).

- National Floor Wage: Sets a statutory baseline; States cannot fix wages below it.

- Uniform Wage Definition: Wage includes basic pay, dearness allowance, and retaining allowance; minimum 50% of total remuneration for social security calculations.

- Working Hours & Overtime: Capped at 8 hours/day, 48 hours/week; overtime at twice the normal wage.

- Timely Payment & Documentation: Strict timelines for wage payment; mandatory wage slips (physical/electronic).

- Deductions: Not to exceed 50% of total pay.

2. Code on Social Security, 2020

- Expanded Coverage: Integrates nine laws and extends benefits to organised, unorganised, gig, and platform workers—defined for the first time.

- Social Security Fund: For unorganised, gig, and platform workers; funded by Centre/States, CSR, and aggregator contributions (1–2% of turnover; capped).

- Parity for Fixed-Term Employees: Eligible for gratuity after one year (earlier five years for permanents).

- Wider ESIC & EPF Reach: Nationwide ESIC; mandatory even for a single worker in hazardous occupations; EPF to establishments with 20+ workers irrespective of industry.

- Administrative Reforms: Inspector-cum-facilitators; web-based inspections; time-bound EPF inquiries.

- Worker-Centric Additions: Accidents during commute treated as employment-related; expanded family definition for female employees.

3. Industrial Relations Code, 2020

- Consolidation: Merges laws on trade unions, standing orders, and industrial disputes.

- Fixed-Term Employment (FTE): Permitted with equal benefits; intended for seasonal/short-tenure needs.

- Thresholds: Prior government approval for layoff/retrenchment/closure raised from 100 to 300 workers.

- Strikes & Disputes: Notice requirement extended to all establishments; expanded definition of strike (includes mass casual leave).

- Collective Bargaining: Sole negotiating union with 51% membership; otherwise, a negotiating council with proportional representation.

4. Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSH) Code, 2020

- Consolidation: Integrates 13 laws (Factories, Mines, Plantations, etc.).

- Simplified Compliance: Single registration, common licences, electronic filings; higher thresholds for factory licensing.

- Contract Labour: Threshold raised to 50 workers; conditional use in core activities permitted.

- Women’s Participation: Night work allowed with consent and safety safeguards.

- Migrant Workers: Expanded definition; portability of PDS and social security; annual travel allowance.

- Workplace Safety: Mandatory appointment letters; free annual health check-ups; safety committees for large establishments.

Rationale for Reform

- Fragmentation & Obsolescence: Multiple, overlapping laws unsuited to modern industry and new forms of work.

- High Compliance Costs: Burdensome licensing and reporting, especially for MSMEs.

- Coverage Gaps: Informal and gig workers largely excluded earlier.

- Global Competitiveness: Need for predictable, transparent labour regulation to attract investment.

- Formalisation & Employment: Simplified rules to encourage job creation and transition to formal work.

Key Concerns and Critiques

- MSME Compliance Load: Expanded ESIC/EPF and safety norms may raise costs and require digital capacity.

- Federal Coordination: Labour is on the Concurrent List; divergent State rules risk uneven protections.

- Industrial Relations: Higher thresholds and strike regulations may dilute worker bargaining power; 51% rule may marginalise smaller unions.

- Job Security: Potential overuse of FTE could increase precarity; litigation risk over disguised permanency.

- Awareness Gap: Informal and migrant workers may not fully access new entitlements during transition.

Constitutional Context

- Preamble Values: Justice, equality, dignity guide labour law interpretation.

- Fundamental Rights:

- Articles 14–18: Equality and non-discrimination.

- Articles 19–22: Freedom of association (trade unions).

- Articles 23–24: Prohibition of forced and child labour.

- Article 21: Right to dignified working conditions.

- Judicial Precedents: Bandhua Mukti Morcha, PUDR, Neerja Chaudhary expanded labour rights and rehabilitation.

Way Forward

- Uniform Implementation: Model rules or an intergovernmental labour council to harmonise State regulations.

- Safeguards on FTE: Clear limits, audits, and grievance redress to prevent misuse.

- Gig Worker Security: A dedicated national policy with enforceable aggregator contributions.

- MSME Support: Digital helpdesks, simplified filings, and transitional fiscal support.

- Capacity Building: Worker awareness drives and institutional strengthening for inspectors-facilitators.

Conclusion

The four Labour Codes mark a structural shift toward a simpler, inclusive, and future-ready labour ecosystem balancing worker welfare with business efficiency. Their success hinges on cooperative federalism, robust safeguards against misuse, and effective on-ground implementation to ensure that growth and dignity at work advance together.

DefenceAtmanirbharta

- 24 Nov 2025

In News:

India’s defence sector has undergone a structural transformation over the past decade, marked by record production, expanding exports, and deepening indigenisation. In FY 2024–25, India achieved its highest-ever defence production of ?1.54 lakh crore, while defence exports touched a record ?23,622 crore, reflecting the tangible outcomes of the Atmanirbhar Bharat vision in the strategic domain. This shift signifies India’s transition from one of the world’s largest defence importers to an emerging global manufacturing and export hub.

Rising Production and Export Trajectory

Indigenous defence production rose sharply from ?46,429 crore in FY 2014–15 to ?1,27,434 crore in FY 2023–24, registering a growth of about 174%. This expansion has been supported by sustained budgetary commitment, with the defence budget increasing from ?2.53 lakh crore (2013–14) to ?6.81 lakh crore (2025–26). In FY 2024–25 alone, the Ministry of Defence signed 193 contracts worth ?2.09 lakh crore, of which 177 contracts were awarded to domestic industry, reinforcing the “Buy Indian” approach.

Defence exports, once negligible at less than ?1,000 crore in 2014, have grown steadily, with India now exporting to 80–100 countries. Both Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs) and the private sector have contributed, with the latter’s share rising to 23%, supported by nearly 16,000 MSMEs supplying subsystems, components, and niche technologies.

Policy Reforms Driving Self-Reliance

This growth has been underpinned by far-reaching reforms. The Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020prioritised the Buy (Indian–IDDM) category, streamlined approvals, and embedded advanced technologies such as AI, cyber, and space systems into procurement. Complementing this, the Defence Procurement Manual (DPM) 2025 simplified revenue procurement worth nearly ?1 lakh crore annually, standardised procedures, enhanced digitalisation, and reduced compliance burdens for industry.

Other key enablers include Positive Indigenisation Lists restricting imports of thousands of items, liberalisedFDI norms (74% automatic, 100% via approval), the ?1 lakh crore Research, Development and Innovation (RDI) Scheme, and innovation platforms such as iDEX and the Technology Development Fund. The restructuring of the Ordnance Factory Board into seven DPSUs improved autonomy and efficiency, while Defence Industrial Corridors in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu attracted over ?9,000 crore in investments, creating manufacturing clusters.

Defence Exports as Strategic Outreach

Export facilitation has been simplified through digital authorisation portals, Open General Export Licences, and rationalised SOPs, resulting in faster clearances and a wider exporter base. Defence exports are increasingly viewed as instruments of diplomacy, fostering interoperability, long-term partnerships, and strategic trust through training, maintenance, and logistics support alongside equipment sales.

Persistent Challenges

Despite progress, challenges remain. India still depends on imports for critical technologies such as propulsion systems, advanced sensors, electronics, and special materials. Production scale is yet to fully match the Armed Forces’ growing requirements, and DPSUs face stiff competition in global markets. Policy–implementation gaps, bureaucratic delays, and dependence on foreign supply chains continue to constrain competitiveness.

Way Forward

Sustaining momentum requires deep-tech capability building, higher defence R&D spending, stronger private-sector participation, and accelerated procurement reforms. Leveraging export diplomacy, long-term procurement commitments, and ecosystem-based innovation can help India achieve its targets of ?3 lakh crore defence production and ?50,000 crore exports by 2029.

Conclusion

India’s defence sector has entered a decisive phase of Atmanirbharta, with record production, rising exports, and a broad-based industrial ecosystem. If structural reforms are consistently implemented and technological depth is strengthened, India is well-positioned to emerge as a globally competitive defence manufacturing hub by the end of this decade, enhancing both national security and economic growth.

India’s Fisheries and Aquaculture: Advancing the Blue Transformation

- 23 Nov 2025

In News:

World Fisheries Day 2025 highlighted India’s remarkable rise as a global fisheries and aquaculture powerhouse, while also underscoring the need for urgent policy and sustainability reforms. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) called for a renewed commitment to India’s Blue Transformationa shift from production-centric growth to value addition, ecosystem sustainability, and inclusive livelihoods.

Growth Trajectory and Global Standing

Over the past four decades, India’s aquatic food production has expanded dramaticallyfrom about 2.4 million tonnes in the 1980s to nearly 17.5 million tonnes in 2022–23. This growth has been driven primarily by inland aquaculture, which has become the backbone of India’s fisheries economy. According to FAO’sState of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA) 2024, India is now the world’s second-largest aquaculture producer, contributing over 10 million tonnes of aquatic animals annually, second only to China.

Inland fisheries have recorded particularly strong growth, rising by around 140% over the last decade, while total fish production nearly doubled. Marine products exportsled by high-value shrimpcontinue to strengthen India’s external trade footprint, supported by improvements in processing, cold chains, and value addition. The sector sustains nearly 30 million livelihoods, with coastal fishing villages accounting for over two-thirds of national output, underscoring the close link between fisheries growth and coastal ecosystem health.

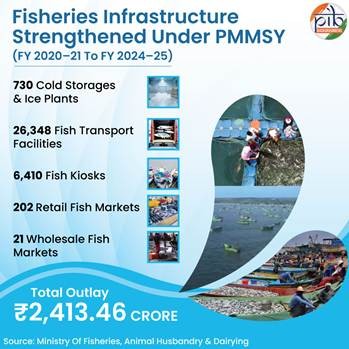

Policy Push and Institutional Support

India’s fisheries expansion has been backed by sustained policy and institutional reforms. The Pradhan Mantri MatsyaSampada Yojana (PMMSY), with an outlay exceeding ?20,000 crore, has strengthened infrastructure through cold storages, transport facilities, fish kiosks, and landing centres, while also promoting fisher welfare, digital inclusion, and safety at sea. Complementary initiatives such as climate-resilient coastal fishermen villages, vessel tracking systems, and the Marine Fisheries Census 2025 aim to improve resilience, targeting, and governance.

Regulatory and scientific institutionssuch as ICAR fisheries institutes, the Marine Products Export Development Authority, and the National Fisheries Development Boardhave promoted innovation, best practices, and environmental compliance. FAO-supported projects, including climate-resilient aquaculture models in Andhra Pradesh and ecosystem-based fisheries management initiatives in the Bay of Bengal, further reinforce sustainability-oriented reforms.

Emerging Opportunities

India’s blue economy potential is expanding through deeper engagement with global seafood markets, improved traceability systems, and new rules for the sustainable harnessing of the Exclusive Economic Zone. Digital platforms for traceability and certification can help Indian exports meet stringent international standards, improving price realisation and reducing rejection risks. Women-centric interventions under PMMSY and allied schemes also open avenues for inclusive growth through processing, retail, and value-added activities.

Persistent Challenges

Despite rapid progress, structural challenges remain. Overfishing and juvenile catch continue to stress nearshore stocks, while habitat degradationthrough pollution, sedimentation, and seagrass lossundermines nursery grounds. Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing erodes sustainability and equity. Post-harvest losses remain high, and small-scale fishers often face limited access to credit, insurance, and modern technology. Climate change further amplifies risks through extreme weather, warming waters, and disease outbreaks in aquaculture.

Way Forward

The FAO’s call for renewed commitment emphasisesscience-based stock management, expansion of deep-sea fisheries to reduce coastal pressure, robust traceability and certification, and biosecure, climate-resilient aquaculture systems. Investing in resilient harbours, early warning systems, and ecosystem-based approaches will be critical to safeguard livelihoods and biodiversity.

Conclusion

India’s fisheries and aquaculture sector stands at a pivotal moment. Having achieved scale and global prominence, the next phase of India’s Blue Transformation must prioritise sustainability, value addition, and inclusivity. With coordinated policy action, scientific management, and strong institutional support, India can convert its fisheries momentum into a resilient, competitive, and environmentally responsible blue economy that secures livelihoods, nutrition, and long-term ecological balance.

Blue NDC Challenge at COP30

- 22 Nov 2025

In News:

At COP30 in Belém, 17 countriesincluding France, Brazil, Belgium, Canada, and Singaporejoined the Blue NDC Challenge, signalling a global push to integrate ocean-based climate solutions into national climate plans under the Paris Agreement.

What is the Blue NDC Challenge?

- A global voluntary initiative encouraging countries to embed ocean-related mitigation and adaptation actions into their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

- Seeks to close the “ocean opportunity gap”, as oceansdespite covering ~70% of Earthreceive <1% of global climate finance and are underrepresented in mitigation plans.

Key Features

- Expanded Membership: Coalition now includes 17 countries, with recent entrants such as Belgium, Canada, Indonesia and Singapore.

- Ocean Taskforce: Supported by France and Brazil to assist governments in integrating ocean solutions into updated 2030 NDCs and translating commitments into policy and implementation.

- Blue Package: A coordinated action framework across five Ocean Breakthrough sectors:

- Marine conservation

- Ocean (aquatic) food systems

- Offshore renewable energy

- Shipping decarbonisation

- Coastal tourism

- Mitigation & Adaptation Focus:Recognises oceans’ potential to deliver up to ~35% of global emission reductions required for the 1.5°C target.

- Blue Carbon Pathways: Integration of mangroves, seagrasses and salt marshes into national mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Why Oceans Matter for Climate Action

- High Mitigation Potential: Offshore renewables, low-carbon shipping, and sustainable fisheries can significantly cut emissions.

- Adaptation & Resilience: Coastal ecosystems protect shorelines, support livelihoods, and enhance food security.

- Underfunded Sector: Ocean-related actions account for <1% of global climate finance, despite large co-benefits.

Global Context

- A growing majority of countries now include ocean priorities in their NDCs, but adaptation dominates, while mitigation commitments remain limited.

- Conservation and blue carbon are most common; shipping decarbonisation, offshore renewables, and low-carbon aquatic food systems are underrepresented.

Significance of the Initiative

- Mainstreams the Ocean–Climate Nexus in national climate policy.

- Mobilises Finance & Technical Support through coordinated action and partnerships.

- Links Climate Action with Development: Job creation, clean energy expansion, biodiversity protection, and coastal community resilience.

- Supports Synergy across global environmental frameworks (climate, biodiversity, sustainable development).

Supreme Court on Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021

- 21 Nov 2025

In News:

In a landmark judgment delivered in November 2025, the Supreme Court of India struck down key provisions of the Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021, holding them unconstitutional for violating the principles of judicial independence, separation of powers, and equality before law. The Court also directed the Union Government to establish a National Tribunal Commission (NTC) within four months, terming it an “essential structural safeguard” for the tribunal system.

Background: Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021

The Tribunal Reforms Act was enacted in August 2021, soon after the Supreme Court had struck down the Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021. The Act sought to:

- Abolish several specialised tribunals and transfer their functions to High Courts.

- Centralise appointments and service conditions of tribunal members.

- Fix short tenures (4 years), impose a minimum age of 50 years, and empower the executive to frame rules on salaries and allowances.

The stated objectives were efficiency, uniformity, and rationalisation. However, critics argued that it enhanced executive dominance over tribunals where the Union Government is often the largest litigant.

Supreme Court’s Key Findings

A Bench led by the Chief Justice held that the Act amounted to an impermissible “legislative override” of binding Supreme Court judgments, particularly the Madras Bar Association (MBA) IV & V cases. The Court noted that Parliament had merely “repackaged” provisions already struck down, without curing the underlying constitutional defects.

The Court struck down provisions that:

- Reintroduced a 4-year tenure, undermining security of office.

- Fixed a minimum age of 50 years, excluding younger advocates and experts.

- Allowed the executive to choose from a panel of names, diluting the role of independent selection committees.

- Tied service conditions of tribunal members to those of civil servants.

The Bench emphasised that norms on tenure, age limits, qualifications, and appointment procedures are not abstract judicial preferences but constitutional requirements flowing from Articles 323A and 323B, read with Article 14 and the basic structure doctrine.

National Tribunal Commission: Court’s Direction

The Court directed the Centre to establish a National Tribunal Commission within four months. The NTC is envisaged as an independent body responsible for:

- Appointments and evaluation of tribunal members.

- Administration, infrastructure, and staffing of tribunals.

- Ensuring uniform standards and insulating tribunals from day-to-day executive control.

Until a fresh, constitution-compliant law is enacted, the safeguards laid down in the MBA judgments will continue to govern tribunal functioning.

Significance of the Judgment

- Reaffirmation of Judicial Independence: The ruling reinforces that tribunals, though statutory, perform core judicial functions and must remain free from executive influence.

- Limits on Parliamentary Power: While Parliament can legislate on tribunals, it cannot nullify or bypass constitutional defects identified by the Supreme Court through re-enactment.

- Protection of Separation of Powers: By rejecting executive dominance in appointments and service conditions, the Court preserved the balance among organs of the State.

- Institutional Reform through NTC: The judgment revives the long-pending idea of a National Tribunal Commission as a systemic solution rather than ad hoc reforms.

Way Forward

The verdict underscores the need for a fresh tribunal law aligned with constitutional principles—ensuring reasonable tenure (at least five years), transparent and merit-based appointments, and institutional autonomy. Strengthening tribunals through the NTC, rather than weakening them or overburdening High Courts, is essential for delivering speedy, specialised, and impartial justice.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision is a decisive assertion of constitutional supremacy and a reminder that efficiency-driven reforms cannot come at the cost of judicial independence. By striking down the Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021, and mandating the creation of a National Tribunal Commission, the Court has laid down a principled roadmap for sustainable and constitutionally compliant tribunal reform in India.

ATC Automation Failure at Delhi IGI Airport

- 20 Nov 2025

In News:

In November 2025, air traffic operations at Indira Gandhi International Airport, India’s busiest aviation hub, were severely disrupted due to a prolonged technical failure in the Automatic Message Switching System (AMSS). The outage, which lasted for more than 24 hours, delayed over 800 flights and had cascading effects across the national aviation network. While flight safety was not compromised, the incident exposed critical vulnerabilities in India’s air traffic control (ATC) automation infrastructure and underscored the urgency of systemic modernisation.

Role of AMSS in Air Traffic Management

AMSS functions as the core communication backbone of ATC operations in major Indian metros such as Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. It automatically receives, stores and routes vital aeronautical messages via the Aeronautical Fixed Telecommunications Network (AFTN) and its modern successor, the Aeronautical Message Handling System (AMHS). These messages include flight plans, departure and arrival updates, NOTAMs, meteorological data and coordination messages between airlines and controllers. Crucially, AMSS feeds data into the Flight Data Processing System (FDPS), which enables ATC automation.

When AMSS failed at Delhi, controllers could see aircraft on radar but lacked access to flight plan data such as routes, altitudes and timings. As a result, more than 2,500 daily aircraft movementsincluding scheduled flights and overflightshad to be managed manually, significantly slowing operations and increasing workload.

Causes and Vulnerabilities

Preliminary assessments point to synchronisation failure between primary and standby servers, delayed system switchover and corrupted message queues. These issues were aggravated by structural weaknesses in the system: legacy server architecture supplied by a foreign vendor, outdated message-switching software, limited redundancy and poor integration with automation and network routers. A shortage of specialised local technical expertise further delayed resolution.

The incident corroborated warnings raised earlier by the Air Traffic Controllers’ Guild and echoed in the Parliamentary Standing Committee’s 380th Report (August 2025), which flagged performance degradation, system lag and outdated functionalities in ATC automation at major airports.

Broader Implications

India’s air traffic systems lag behind global benchmarks such as Federal Aviation Administration and Eurocontrol, which deploy AI-enabled conflict detection, predictive traffic flow analytics and seamless real-time data sharing. In India, the absence of such tools forces Air Traffic Controllers to compensate manually, increasing cognitive load and the risk of human error. With air traffic volumes growing rapidly, these technological gaps constrain airspace capacity and operational efficiency.

Compounding concerns were reports of possible GPS spoofing incidents around the same time, prompting an inquiry by national security authorities. Though no direct causal link was established, the coincidence highlighted the need for resilient systems capable of handling concurrent technological disruptions.

Government Response and Way Forward

The Ministry of Civil Aviation directed the Airports Authority of India to conduct a root-cause analysis, install additional backup servers and accelerate migration from AMSS to a modern, nationwide AMHS-based system with automatic failover. Plans also include deploying ADS-B ground stations, enhancing automation tools and shifting towards satellite-based navigation.

Conclusion

The Delhi IGI ATC glitch was not merely a technical failure but a systemic warning. It revealed the risks of operating critical national infrastructure on aging technology amid surging traffic volumes. For India to sustain safe, efficient and globally competitive aviation growth, urgent, comprehensive modernisation of air traffic managementcombining redundancy, advanced analytics and skilled manpoweris indispensable.

Belem Health Action Plan Launched at COP30

- 19 Nov 2025

In News:

The 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) held in Belém, Brazil, marked a major turning point in global climate governance by placing human health at the centre of climate adaptation discourse. The launch of the Belém Health Action Plan (BHAP) and the announcement of a $300 million commitment by over 35 global philanthropies under the Climate and Health Funders Coalition represent the first coordinated global effort to link climate adaptation finance with public health outcomes. This shift acknowledges that climate change is no longer an environmental issue alone but a multidimensional crisis with profound implications for human health, equity and development.

Climate-linked health risks have intensified sharply, as highlighted in the 2025 Lancet Countdown Report on Health and Climate Change. Heat-related deaths have increased by 23% since the 1990s, reaching 546,000 annually. Wildfire smoke contributed to 154,000 deaths in 2024, while dengue transmission potential has risen by 49% since the 1950s. According to Lancet findings, 3.3 billion people are at heightened health risk from rising temperatures, pollution, extreme rainfall, water scarcity, vector-borne diseases and extreme events. These impacts disproportionately affect vulnerable groups—children, pregnant women, elderly people, outdoor workers and communities with fragile health systems—worsening global health inequities.

In this context, the Belem Health Action Plan, endorsed by more than 80 countries and organisations, seeks to build climate-resilient, equitable and adaptive health systems. The BHAP outlines five key focus areas:

(1) strengthening surveillance and early-warning systems for heatwaves, floods, extreme weather and infectious diseases;

(2) accelerating research and innovation in climate-sensitive health risks and technologies;

(3) promoting health equity and justice by protecting vulnerable communities;

(4) building capacity in healthcare workforces for climate-related emergencies; and

(5) aligning health, climate, and development policies for coherent action.

A core emphasis of the plan is “shifting funding and power to frontline communities,” ensuring that adaptation resources directly reach the most affected.

The $300 million philanthropic commitment complements the BHAP by supporting integrated climate-health solutions. This inaugural funding tranche will prioritize extreme heat mitigation, expansion of early-warning systems, reduction of air pollution, and improved management of climate-sensitive diseases such as malaria, dengue and cholera. A major component involves integrating climate and health data platforms, enabling real-time forecasting and targeted responses. The initiative also stresses the urgency of action, with the past decade recorded as the hottest in human history, and projections indicating continued extreme temperatures.

However, COP30 also highlighted a persistent adaptation finance gap, especially for health-focused interventions. The UN Adaptation Gap Report (2025) estimates that developing countries will require $310–365 billion annually by 2035 to meet adaptation needs, while current global flows average just $40 billion per year. Health-related adaptation receives an even smaller share. India’s 2023 National Communication to the UNFCCC projects a need for $643 billion by 2030 for adaptation, though the country has significantly scaled up domestic spending to $146 billion (5.6% of GDP) in 2021–22.

The Belem outcome reflects a paradigm shift—viewing climate adaptation not merely as environmental protection but as safeguarding human lives, livelihoods and health systems. By institutionalising a climate-health framework, strengthening collaborations between governments, global agencies and philanthropies, and expanding financing avenues, COP30 has laid the foundation for a more people-centred climate agenda. The challenge now lies in rapidly operationalising BHAP’s strategies at national and local levels, ensuring robust funding, and building resilient health systems capable of withstanding an increasingly volatile climate future.

National Migration Survey 2026

- 18 Nov 2025

In News:

The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) has announced that a comprehensive National Migration Survey will be conducted between July 2026 and June 2027 under the National Sample Survey (NSS) framework. This marks the first dedicated migration-focused nationwide survey since the 64th NSS Round (2007–08) and aims to address the critical data gap that became particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when large-scale reverse migration exposed structural vulnerabilities in internal mobility systems.

Migration in India is a complex socio-economic phenomenon driven largely by employment, marriage, education, and search for better living conditions. As per the PLFS 2020–21, nearly 28.9% of India’s population were migrants. Female migration dominates in rural areas (48%), largely due to marriage, while male migration is predominantly employment-led (67%). Major flows continue to be rural-to-urban and inter-state, especially from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Odisha towards industrial centres in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Delhi, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Migration contributes significantly to India’s urbanisation, labour markets, and remittance-driven rural resilience, yet also presents challenges such as precarious employment, lack of social security portability, and inadequate housing in destination areas.

Objectives and Structure of the 2026 Survey

The survey will cover almost all states and union territories (excluding Andaman and Nicobar Islands due to logistical constraints). Its key objectives include generating reliable national and regional estimates of:

- Migration rates (rural-to-urban, inter-state, intra-state)

- Seasonal and short-term migration

- Socio-economic drivers (employment, education, marriage)

- Employment outcomes and earnings of migrants

- Return migration and post-migration welfare impacts

A significant conceptual revision introduced in this survey is the updated definition of short-term migration. A person staying away from the usual residence for 15 days to six months for work or job search will now be classified as a short-term migrant—compared to the earlier threshold of one to six months. This change aligns with emerging patterns of circular and temporary mobility linked to gig work, construction, and agricultural seasonality.

In contrast to earlier surveys that emphasised household migration, the new framework prioritisesindividual migration patterns, recognising that entire households rarely migrate together. The questionnaire also expands into new domains, including housing conditions, access to healthcare, local integration challenges, remittance behaviour, and intent for future relocation.

Relevance for Policy and Governance

MoSPI has emphasised that findings from the survey will inform evidence-based policymaking across multiple sectors. For urban development, migration data will support planning related to affordable housing, transportation, slum rehabilitation, and spatial infrastructure. In labour markets, such data can help identify sectoral skill shortages and improve workforce mobility. The survey will also guide the design of portable social protection frameworks, including ration cards, health insurance, pensions, and direct benefit transfers for migrant workers.

Furthermore, understanding remittance flows is crucial for rural development, as remittances bolster household consumption, education expenditure, and healthcare access. Migration data also supports regional planning by assessing demographic pressures in receiving states and labour shortages in sending areas.

Conclusion

The National Migration Survey 2026 represents a critical step in modernising India’s migration statistics architecture. By updating definitions, expanding coverage, and capturing short-term and circular migration, it will generate robust evidence to inform labour mobility policies, urbanisation strategies, and welfare systems. Importantly, it bridges a 19-year gap since the last dedicated migration survey, providing policymakers with timely data to design interventions that balance the opportunities and challenges posed by internal migration in a rapidly transforming economy.

India’s Carbon Emissions Slowdown: Insights from the Global Carbon Project 2025

- 17 Nov 2025

In News:

The Global Carbon Project’s (GCP) 2025 assessment presents a crucial shift in India’s carbon emissions trajectory, showing a rise of only 1.4% in 2025 compared to the 4% increase recorded in 2024. This moderation is significant for a country that remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, particularly coal, and is the third-largest emitter in the world after China and the United States. While India’s emissions continue to grow in absolute terms, the rate of growth has slowed considerably, indicating structural changes driven by renewable energy expansion, improved energy efficiency, favourable weather conditions, and long-term policy planning.

India’s fossil-fuel CO? emissions are projected to increase from 3.19 billion tonnes in 2024 to 3.22 billion tonnes in 2025, but its per-capita emissions remain at 2.2 tonnes, among the lowest within the G20 economies. Historically, India’s annual emission growth averaged 6.4% between 2005–2014, reducing to 3.6% during 2015–2024, reflecting improvements in carbon intensity and a shift toward cleaner energy systems. The slowdown in 2025 is partly attributed to a strong monsoon, which reduced cooling needs and irrigation demand, thereby lowering electricity consumption and limiting the rise in coal usage. Additionally, India’s rapid renewable energy expansion—now accounting for 50.07% of total installed power capacity (484.82 GW)—has played a decisive role in containing emissions growth. The country has already achieved its COP26 target of 50% non-fossil capacity five years ahead of schedule, with 242.8 GW in non-fossil sources, and continues progressing toward its 500-GW renewable capacity target for 2030.

Global trends, however, remain concerning. Fossil-fuel CO? emissions worldwide are expected to rise 1.1% in 2025, reaching 38.1 billion tonnes, with emissions from coal, oil and gas increasing by 0.8%, 1% and 1.3% respectively. China—responsible for the largest share of global emissions—shows moderation with growth at just 0.4%, driven by record-level renewable installations. Despite incremental progress in land-use emissions reduction, total global CO? emissions remain flat at around 42 billion tonnes, leaving the world off-track to meet the 1.5°C climate target. The GCP cautions that only 170 billion tonnes of CO?remain in the global carbon budget compatible with the 1.5°C threshold—equivalent to just four years of emissions at current rates—rendering the target increasingly unrealistic.

Within India, sectoral analysis shows the energy sector accounts for 75.66% of total greenhouse gas emissions, while land-based activities sequestered 522 million tonnes of CO? in 2020 (22% of national emissions). India’s 4th Biennial Update Report (BUR-4) to the UNFCCC recorded a 7.93% decline in 2020 emissions due to pandemic-related demand reduction. Coal remains dominant, but clean-energy additions helped reduce power-sector CO? emissions by 1% in early 2025.

India’s response is articulated through its Long-Term Low Emission Development Strategy (LT-LEDS)centred on seven pillars:

- Clean electricity

- Low-carbon transport

- Inclusive urban adaptation

- Decarbonised industry

- Atmospheric CO? removal

- Tree and vegetation enhancement, and

- A net-zero-aligned economic framework aimed at achieving Net Zero by 2070.

In conclusion, while India’s emission slowdown reflects encouraging structural transitions and successful renewable energy deployment, sustained progress will require deeper industrial decarbonisation, resilient energy systems, and accelerated policy action to navigate rising global climate risks and narrowing carbon budgets.

Draft Seeds Bill 2025: Reforming India’s Seed Regulatory Framework

- 16 Nov 2025

In News:

The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare has released the Draft Seeds Bill 2025 for public consultation, proposing a comprehensive overhaul of India’s seed governance architecture. The Bill seeks to replace the outdated Seeds Act, 1966 and the Seeds (Control) Order, 1983, reflecting the need to align India’s seed sector with contemporary agricultural technologies, global market trends, and quality assurance norms. Earlier attempts to introduce new seed legislation in 2004 and 2019 faced widespread farmer resistance and were ultimately withdrawn. The 2025 draft attempts a more balanced approach that strengthens quality standards while safeguarding farmers’ rights.

A central objective of the Bill is to ensure quality, affordability, and traceability of seeds. It mandates regulatory oversight over the sale, import, export, and distribution of seeds, requiring conformity to the Indian Minimum Seed Certification Standards, which define minimum limits for germination, genetic purity, physical purity, seed health, and trait expression. This shift aims to curb the rampant sale of substandard and spurious seeds that have often resulted in crop losses for farmers.

A defining feature of the Bill is the introduction of mandatory registration for all seed varieties, except farmers’ varieties and varieties produced exclusively for export. Existing notified varieties under the 1966 Act will be deemed registered, ensuring continuity while improving accountability. Registration of seed dealers and distributors with State authorities is also compulsory, bringing uniformity and transparency into the seed supply chain. The Bill also allows controlled liberalisation of seed imports, enabling entry of unregistered varieties for research and trials, with the aim of promoting innovation and access to global germplasm.

The draft introduces a graded penalty structure, classifying offences into trivial, minor, and major categories. Major offences include the sale of non-registered or spurious seeds and operating without proper registration. These attract stiff penalties of up to ?30 lakh and imprisonment of up to three years, signalling the government’s intent to curb malpractice. Minor offences are proposed to be decriminalised to encourage compliance and enhance ease of doing business for legitimate seed enterprises.

Institutionally, the Bill provides for Central and State Seed Committees to coordinate policy, regulate certification procedures, and oversee enforcement mechanisms. This is expected to strengthen federal-level harmonisation in an area where seeds fall under central regulation, but agriculture remains a State subject.

Stakeholder responses to the draft have been mixed. Seed industry associations have welcomed the Bill, highlighting that it will modernise the regulatory environment, support innovation, and bring clarity to seed registration norms. The Federation of Seed Industry of India (FSII) has endorsed its emphasis on research-driven seed development. However, farmer organisations continue to express apprehension, viewing the Bill as potentially “pro-corporate,” with fears of increased dependence on private and multinational companies. Concerns persist regarding compliance burdens for small producers and the potential dilution of farmers’ autonomy in seed selection and exchange.

To ensure the Bill’s effective implementation, several challenges need to be addressed—strengthening laboratory and certification infrastructure, harmonising central–state coordination, ensuring transparency in seed testing, and safeguarding farmers’ traditional rights to save, use, exchange, and sell their own varieties (except branded seeds). Additionally, enhancing investments in public sector seed research through ICAR and State Agricultural Universities remains crucial to balance private sector dominance.

In conclusion, the Draft Seeds Bill 2025 represents a significant step toward modernising India’s seed regulatory ecosystem. Its success will depend on inclusive stakeholder consultations, robust enforcement mechanisms, and a regulatory framework that balances farmer protection with innovation and industry growth.

Strengthening Regulatory Governance

- 15 Nov 2025

In News:

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has initiated a major reform process aimed at enhancing transparency, accountability, and ethical conduct within the organisation. In response to concerns over conflicts of interest and allegations involving former SEBI Chairperson Madhabi Puri Buch and offshore financial links—claims denied by the individuals involved—the regulator constituted a High-Level Committee (HLC) in March 2025. This six-member panel, led by former Chief Vigilance Commissioner Pratyush Sinha, has proposed a comprehensive set of ten recommendations intended to overhaul SEBI’s internal governance standards and align them with global best practices followed by regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA).

A key recommendation of the HLC is the establishment of a multi-tier disclosure framework. The Chairperson, Whole-Time Members (WTMs), and senior officials at the level of Chief General Manager (CGM) and above would be required to publicly disclose their assets and liabilities, covering movable and immovable property, investments, and outstanding liabilities. All other employees would file internal disclosures detailing their financial interests, professional relationships, and connections with relatives as defined under the Companies Act, 2013. This framework aims to strengthen public confidence in the regulator’s independence and integrity.

Another critical reform area involves mandatory conflict-of-interest declarations at the time of appointment. Applicants for top SEBI positions must disclose actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of both financial and non-financial nature. Such early disclosures allow the appointing authority to assess ethical suitability and mitigate risks before onboarding senior personnel.

The committee also recommended stringent investment and trading restrictions for SEBI leadership and employees. New investments should be limited to professionally managed pooled funds regulated by Indian financial regulators. For existing investments held at the time of appointment or joining, senior officials must choose among four options: liquidation, freezing, sale through a pre-approved trading plan, or sale with prior SEBI approval. Further, the HLC has advised that the Chairperson and WTMs be classified as “insiders” under the SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015, placing them under enhanced scrutiny and disclosure obligations.

To ensure consistency, the committee proposed a broader definition of ‘family’. The revised definition would include spouses, dependent children, individuals for whom officials are legal guardians, and persons related by blood or marriage who are substantially dependent on the employee. This harmonisation between the SEBI Code of Conduct (2008) and the SEBI Employees’ Service Regulations (2001) seeks to remove ambiguities in assessing indirect conflicts of interest.

The HLC also recommended a blanket ban on acceptance of gifts from entities that have or may have official dealings with SEBI. A structured recusal mechanism must be institutionalised, requiring officials to step aside from decision-making roles in matters where conflicts exist. An annual summary of recusals by top officials should be included in SEBI’s Annual Report to enhance transparency.

Finally, the committee proposed post-retirement restrictions, preventing former members and employees from representing parties before SEBI for two years after exit. It also advocated a secure, confidential, anonymous whistle-blower system open not just to employees but also to market intermediaries and the public, ensuring a broad-based mechanism to detect ethical breaches.

Once approved by the SEBI Board and the Ministry of Finance, these recommendations will be incorporated into SEBI’s revised Code of Conduct with prospective applicability. Collectively, these reforms aim to fortify regulatory governance, restore public trust, and uphold the autonomy and integrity of India’s capital markets ecosystem.

Rare Earths, China’s Leverage and Lessons for Global and Indian Strategy

- 14 Nov 2025

In News:

Rare earth elements (REEs) have emerged as a critical geopolitical and economic lever in the 21st century, underpinning technologies central to defence, clean energy, electronics and advanced manufacturing. Recent developments including China’s temporary easing of export controls have highlighted that any relief to global markets is likely to be short-lived. The episode reinforces a deeper structural reality: China’s dominance over rare earth mining, processing and magnet manufacturing gives it enduring strategic leverage.

China’s Rare Earth Dominance

Rare earths comprise 17 chemically similar elements used in high-performance magnets, phosphors, batteries, wind turbines, electric vehicles, missiles and fighter aircraft. While these elements are not geologically rare, economically viable and environmentally manageable deposits are scarce. Over the past three decades, China has systematically built control over the entire value chain from mining to refining to manufacturing.

China’s share in global rare earth mining rose from about 38% in 2020 to nearly 70% in 2023. Its grip is even stronger in processing and refining, where it supplies 85–95% of global demand. Beijing has reinforced this dominance through overseas investments in Africa and Latin America, stakes in processing facilities in Malaysia, and strategic influence in companies such as Australia’s Lynas. Rare earths were formally designated a “strategic mineral” by China in the 1990s, enabling the state to weaponise supply during diplomatic or trade disputes.

Japan’s 2010 Shock: A Strategic Lesson

The clearest early warning came in 2010, when China informally halted rare earth exports to Japan following a maritime dispute. At the time, Japan imported nearly 90% of its rare earths from China, leaving its automobile and electronics industries exposed. Prices surged almost tenfold within a year, revealing the costs of overdependence.

Japan responded with a multi-pronged strategy: stockpiling critical minerals, investing in overseas mines (notably in Australia and Vietnam), expanding recycling, and developing technologies that reduce rare earth intensity. By 2023, Japan had reduced its dependence on China to about 60%. However, the experience also revealed limits partial diversification still leaves room for coercion, while full independence demands sustained, high-cost investment. The fading urgency after crises subside underscores the danger of complacency.

Renewed Global Push: US and EU

China’s recent export restrictions including controls on seven rare earths such as dysprosium, terbium and yttrium have revived concerns in the US and Europe. The US is stockpiling magnets, investing in domestic mining and processing (including Pentagon-backed stakes in firms like MP Materials), and prioritisingdefence supply chains. The European Union has expanded its critical minerals list, pushed for domestic refining, and encouraged recycling and deep-sea mineral research. These efforts reflect a broader “de-risking” approach: reducing vulnerability without severing economic ties.

Implications for India

For India, the immediate impact of China’s controls is limited, but long-term risks are significant. India holds around 6.9 million tonnes of rare earth reserves, mainly in Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan, placing it among the top five globally. Yet production remains minimal about 2,700 tonnes of rare earth oxides in 2023, compared to China’s 2,24,000 tonnes.

Recent policy reforms aim to increase private participation and accelerate exploration. Output has begun to rise, touching nearly 2,900 tonnes in 2023-24 and projected to reach around 5,000 tonnes in coming years. However, slow development, environmental concerns, and limited processing capacity remain constraints. As demand surges from clean energy and defence sectors, India risks strategic vulnerability unless it builds end-to-end capabilities.

Way Forward

The global rare earth challenge underscores three lessons: diversification must be continuous, processing capacity matters as much as mining, and strategic stockpiles are essential. Japan’s experience shows that resilience is built over decades, not crises. For India, aligning mineral policy with industrial strategy, investing in processing and recycling, and forging trusted international partnerships will be critical to safeguarding economic and strategic autonomy in an era of resource geopolitics.

Puducherry’s Community-Led Green Transformation

- 13 Nov 2025

In News:

In an era of accelerating climate change and rapid urbanisation, Indian cities face the dual challenge of ecological degradation and declining public participation in environmental stewardship. Against this backdrop, Puducherry has emerged as an innovative model of community-driven greening, demonstrating how environmental governance can be both scientifically sound and socially embedded. Under the leadership of P. Arulrajan, an Indian Forest Service officer, Puducherry has launched a holistic programme aimed at doubling its green cover by 2030.

Vision and Objectives

Puducherry’s current forest and tree cover stands at about 12.57%, significantly below what is desirable for climate resilience and urban sustainability. The initiative sets an ambitious yet clear goal: to raise green cover to at least 24% by 2030. Unlike conventional afforestation drives that rely primarily on government machinery, Puducherry’s approach places citizens at the centre of ecological restoration, integrating administrative innovation, ecological science, and cultural values.

Key Innovations in the Programme

One of the most distinctive elements is the Spiritual Van Initiative, which links tree planting with traditional belief systems. Citizens are encouraged to plant three trees associated with their planet, rashi, and nakshatra, thereby aligning environmental action with personal and cultural identity. This strategy transforms tree planting from a bureaucratic activity into a value-driven, emotionally resonant practice, increasing long-term ownership and care.

Another pillar is the Amma Vanam Programme, a large-scale plantation drive that has facilitated the planting of over one lakh trees. The programme mobilises diverse social groups, including Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) workers, self-help groups, students, and fishing communities. This convergence not only accelerates plantation efforts but also links livelihood support with environmental outcomes, reinforcing the idea that ecology and economy are interdependent.

To nurture environmental consciousness among children, Puducherry has introduced seed-filled pencils, which can be planted after use. These low-cost tools enable children to green roadsides and unused spaces, embedding eco-literacy and stewardship at an early age. Such micro-interventions, while simple, have a multiplier effect by shaping attitudes rather than merely increasing tree counts.

Ecological and Administrative Dimensions

The programme adopts an integrated green governance model, combining scientific site selection, native species choice, and ecosystem-specific restoration. Special emphasis is placed on sand dune regeneration, urban greening, and coastal ecosystem recovery, which are critical for Puducherry’s vulnerability to cyclones, sea-level rise, and erosion. Rather than isolated plantations, the focus is on functional ecosystems that enhance biodiversity and climate resilience.

Administratively, the initiative demonstrates effective inter-departmental convergence and community partnerships, reducing costs and improving sustainability. Citizen participation also ensures better survival rates of plantations, a common weakness in top-down afforestation programmes.

Significance and Broader Lessons

Puducherry’s greening effort illustrates that environmental policy need not be technocratic or alienating. By grounding conservation in local culture, collective action, and scientific planning, it offers a replicable model for other States and urban regions. The initiative strengthens civic responsibility, promotes inclusive climate action, and aligns well with India’s broader commitments to sustainable development and climate adaptation.

Conclusion

Puducherry’s experience underscores a crucial lesson for contemporary environmental governance: lasting ecological transformation is as much a social process as a scientific one. By harmonising tradition, participation, and policy, Puducherry is not merely planting trees, it is cultivating a culture of sustainability, making its green transition both resilient and people-centric.

Redrawing India’s Welfare Architecture: Placing Universal Basic Income at the Centre

- 12 Nov 2025

In News:

India is entering a phase where rapid economic growth coexists with deepening inequality, labour precarity, and technological disruption. Automation, the expansion of the gig economy, climate-related displacement, and rising mental health stress are reshaping livelihoods faster than policy can adapt. In this context, Universal Basic Income (UBI)-once dismissed as utopian-has re-emerged as a serious policy option to modernise India’s welfare architecture.

What is Universal Basic Income?