Migration and Globalisation

- 31 Aug 2025

Context:

Migration has historically been central to human survival, cultural enrichment, and economic development. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, in a recent interaction with students in Kolkata (August 2025), underlined that migration is not merely a by-product of globalisation but an essential driver of it. He argued that without the movement of people, exchange of ideas, and diversity, “almost nothing would happen” in society. His observations highlight the need to place migration at the core of discussions on inclusive development and global integration.

Migration and Globalisation: A Two-Way Link

Migration represents both a cause and consequence of globalisation. The growing interconnectedness of economies, labour markets, and cultures compels people to move in search of livelihood, education, and security. Conversely, migration sustains the very processes of globalisation by ensuring labour mobility, knowledge transfer, and cultural exchange.

Remittances from international migrants significantly support local economies in poorer regions, while in ageing industrial societies, migrants fill labour shortages and keep welfare systems functional. Similarly, internal migration within developing countries responds to shifts in industrial location and the expansion of tourism, service, and construction sectors.

Economic and Social Contributions of Migrants

Migration plays a critical role in sustaining households and reshaping communities:

- Economic Support: Remittances are often the backbone of rural economies, enabling investments in agriculture, housing, and small enterprises.

- Skill Transfer: Return migrants bring exposure, technology, and non-farm opportunities, provided there is institutional support.

- Cultural Exchange: Migrants enrich host societies by introducing new languages, cuisines, music, and traditions, fostering cosmopolitan growth.

- Empowerment: For many youth and women, migration becomes a pathway to independence, autonomy, and expanded life choices.

Sen himself cited historical examples—such as Arabic translations of Brahmagupta’s mathematical works—that demonstrate how migration and cultural contact drive intellectual advancement.

Key Challenges

Despite its benefits, migration remains highly contested. Restrictive immigration policies in developed nations often strengthen illegal smuggling networks and leave migrants vulnerable to exploitation. Within India, internal migrants frequently face exclusion from basic urban services such as housing, education, and healthcare.

Undocumented and unskilled migrants are particularly prone to labour exploitation, earning low wages under insecure conditions. Women migrants confront additional gender disparities, ranging from wage inequality to social stigma, although they can emerge as strong agents of change where given resources and support.

Policy Imperatives

Migration must be recognised not as a threat but as an enabler of development. The policy framework should:

- Protect migrant rights and improve workplace safety.

- Facilitate the productive use of remittances through training, financial literacy, and infrastructure.

- Ensure equitable access to resources for women migrants.

- Address structural constraints such as rural distress, which force people into migration as a survival strategy.

India has already witnessed tensions, including attacks on migrant workers from West Bengal in other states, highlighting the urgency of a protective and inclusive approach.

Conclusion

Migration is inseparable from globalisation and has historically propelled human progress. It strengthens economies, sustains welfare systems, and enriches cultures. Yet, the absence of supportive policies leaves migrants vulnerable to exclusion and exploitation. As Amartya Sen emphasised, diversity is the foundation of Indian society and the movement of people is the essence of globalisation. Recognising migrants as partners in development rather than problems to be managed is essential for building an inclusive, equitable, and resilient global future.

UGC Draft Curriculum Highlights Ancient Wisdom in Higher Education

- 30 Aug 2025

Background

The University Grants Commission (UGC) has released a draft Learning Outcomes-based Curriculum Framework (LOCF) for undergraduate programmes in fields such as anthropology, chemistry, commerce, economics, geography, mathematics, political science, home science, and physical education.

A defining feature of this framework is the inclusion of Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), aiming to blend traditional philosophies and practices with contemporary pedagogy. The draft has been made public for feedback from stakeholders.

Integration of Indian Knowledge Systems

The framework seeks to position higher education within India’s cultural and intellectual heritage, reflecting the vision of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, which emphasiseddecolonisation of curricula and recognition of indigenous wisdom.

Every subject has been asked to incorporate aspects of Indian traditions, linking them to modern learning outcomes.

Subject-Wise Highlights

- Mathematics

- Modules on mandala geometry, yantras, rangoli, kolam as algorithmic art forms.

- Study of temple architecture through ?y?di ratios.

- Contributions of Indian mathematicians in arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and calculus, and their influence on global traditions.

- Commerce

- Incorporation of Bhartiya philosophy and Gurukul pedagogy, focusing on holistic learning.

- Study of Kautilya’sArthashastra for insights into trade and financial systems.

- Ideas like Ram Rajya, Shubh-labh (profit with responsibility), CSR, and ESG frameworks integrated into modern governance discussions.

- Economics

- Emphasis on dharmic perspectives on wealth and prosperity.

- Exploration of indigenous exchange systems, agrarian values, dana (charity), and state-led economic roles.

- Ethical trade and collective enterprise highlighted as core themes.

- Chemistry

- Introduction of traditional Indian fermented drinks (kanji, mahua, toddy) in modules on alcoholic beverages.

- Integration of parmanu (ancient atomic concept) with modern atomic theory.

- Anthropology

- Curriculum draws on Charaka, Sushruta, Buddha, and Mahavira, focusing on their insights into the relationship between culture and nature.

Criticism and Concerns

- While NEP 2020 promotes interdisciplinarity, the LOCF allocates a large portion of credits to single-major courses. For example, chemistry students must take 96 out of 172 credits in core courses, reducing scope for cross-disciplinary learning.

- Critics, including some opposition-led states, allege that the draft encourages “saffronisation” of education.

- The key challenge lies in ensuring that cultural heritage is respected while preserving academic rigour, scientific temper, and global competitiveness.

Significance

The draft framework represents a paradigm shift in Indian higher education, with potential to:

- Decolonise curricula by embedding indigenous systems.

- Offer culturally rooted yet globally relevant education.

- Encourage ethical, sustainable practices across professional fields.

- Highlight India’s contributions to mathematics, medicine, governance, and economics.

Way Forward

The draft is currently open for feedback and may be revised before implementation. If adopted, it could reshape the intellectual foundation of higher education, grounding it more deeply in India’s heritage while aligning with international standards.

The real challenge, however, will be to ensure that ancient wisdom complements — rather than replaces — critical thinking, scientific inquiry, and multidisciplinary exploration.

Haryana’s New Forest Definition and Its Implications for the Aravallis

- 29 Aug 2025

Introduction

The debate on what constitutes a “forest” in India has resurfaced with the Haryana government’s recent notification defining forests based on “dictionary meaning.” While the state claims its definition aligns with Supreme Court precedents, environmentalists warn that it narrows the scope of protection, particularly threatening the fragile Aravalli ecosystem. The issue reflects the larger legal and ecological contestation over forest governance in India, especially after the 2023 amendment to the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 (FCA).

Haryana’s Definition of Forests

As per the notification (August 18, 2025), a patch of land qualifies as forest if:

- It covers at least 5 hectares in isolation or 2 hectares if contiguous with government-notified forests.

- It has a canopy density of 40% or more.

The definition excludes linear or compact plantations (along roads, canals, railways), agro-forestry plantations, and orchards outside notified forests. Officials argue this provides clarity for surveys mandated by the Supreme Court, but critics fear it sets thresholds too high for naturally sparse ecosystems like the Aravallis.

Supreme Court Directives

In March 2025, the Supreme Court directed all States/UTs to define forests and begin mapping them, in line with the 2011 Lafarge Umiam Mining guidelines. These guidelines mandate:

- A GIS-based decision-support system.

- District-wise mapping of forest-like areas, community lands, eco-sensitive zones, wildlife corridors, and previously diverted forest lands.

- Accountability of Chief Secretaries for non-compliance.

This directive came during hearings on petitions challenging the 2023 FCA amendment (Ashok Kumar Sharma, IFS (Retd) &Ors. vs Union of India).

Godavarman Case and FCA Amendment

The FCA, 1980 originally restricted dereservation and diversion of forest land without Central approval. In the 1996 Godavarman case, the Supreme Court broadened “forest” to its dictionary meaning, bringing all statutorily recognised or naturally forested areas under FCA protection.

However, the 2023 amendment limited FCA applicability to:

- Notified forests, and

- Lands recorded as forests in government records.

The government argued that the Godavarman interpretation hindered developmental projects, even minor ones. Retired IFS officers and NGOs contested this, alleging dilution of forest safeguards. In February 2024, the Court ordered States to continue applying the Godavarman definition until the matter is resolved.

Implications for the Aravallis

The Aravalli range, spread across Haryana, Delhi, Rajasthan, and Gujarat, is ecologically critical for groundwater recharge, biodiversity, and as a green buffer against desertification. Its vegetation is naturally stunted, thorny, and scrub-like due to low rainfall (300–600 mm annually) and rocky terrain. Experts argue that imposing a 40% canopy cover threshold would exclude much of the Aravallis, leaving it open to urbanisation, illegal mining, and real estate encroachments.

Furthermore, the minimum area thresholds (2–5 hectares) are considered too high for a dry state like Haryana, where smaller forest patches play a vital ecological role. Analysts call the state’s approach violative of the Godavarman principle, which recognised even small and degraded forests under FCA protection.

Conclusion

Haryana’s restrictive definition exemplifies the ongoing tension between developmental priorities and ecological safeguards. While compliance with the Supreme Court’s directive is necessary, adopting narrow thresholds risks excluding ecologically fragile zones from legal protection. The debate underscores the need for a balanced, scientifically informed, and ecologically sensitive framework, recognising regional variations in vegetation and ensuring long-term sustainability of ecosystems like the Aravallis.

Criminalisation of Politics in India

- 28 Aug 2025

In News:

The criminalisation of politics—the entry of individuals facing serious criminal charges into legislative bodies—remains one of the gravest challenges to Indian democracy. Despite repeated judicial observations and public debates, the problem has only deepened over the past decade, threatening the integrity of representative institutions.

Scale of the Problem

Recent data highlights the alarming rise in lawmakers with serious criminal records. In the Lok Sabha, the share of MPs with such cases has increased from 14% in 2009 to 31% in 2024, more than doubling in just 15 years. Certain states reflect extreme cases: Telangana (71% of MPs), Bihar (48%), and Uttar Pradesh (34 MPs, the highest in absolute numbers).

At the state level, the trend is equally stark. In 2024, nearly 29% of MLAs (around 1,200) faced serious criminal charges. Andhra Pradesh (56%), Telangana (50%), and Uttar Pradesh (154 MLAs or 38%) illustrate how deeply entrenched the issue has become.

These figures cover offences punishable by five years or more, including non-bailable crimes such as murder, kidnapping, and corruption, thereby going beyond minor infractions.

Causes of Criminalisation

Several systemic factors perpetuate this trend:

- Electoral Financing – High campaign costs create incentives for parties to field “winnable” candidates, many of whom have criminal clout and access to large financial resources.

- Weak Enforcement of Laws – While conviction leads to disqualification under the Representation of the People Act (RPA), slow judicial processes allow accused legislators to contest multiple elections.

- Patronage Politics – Candidates with criminal backgrounds often command local influence, mobilise voters, and provide muscle power for parties, making them electorally attractive.

- Voter Rationality – In certain constituencies, voters see such candidates as problem-solvers who can deliver despite weak state capacity, reinforcing their acceptability.

Consequences for Democracy

The rising criminalisation of politics undermines the rule of law and corrodes democratic legitimacy. Legislators facing serious charges may prioritise personal or group interests over public welfare. Policy decisions risk being distorted by vested interests, while governance is compromised by declining ethical standards. Over time, this erodes citizen trust in institutions, weakens the credibility of Parliament and Assemblies, and fuels cynicism about democratic accountability.

Judicial and Institutional Responses

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasised the need to curb criminalisation. In Lily Thomas v. Union of India (2013), it ruled that convicted legislators would be immediately disqualified. In Public Interest Foundation v. Union of India (2018), it directed parties to publish criminal antecedents of candidates, citing the “urgent need for cleansing politics.”

The Election Commission of India (ECI) has also recommended barring candidates against whom charges have been framed for serious offences. However, political consensus on reforms remains elusive.

Way Forward

Addressing this structural malaise requires a multi-pronged strategy:

- Legal Reforms – Amend the RPA to disqualify candidates at the stage of framing of charges for heinous crimes.

- Judicial Fast-Tracking – Establish special courts for speedy trial of cases against politicians.

- Political Will – Parties must adopt internal reforms, refusing tickets to tainted candidates, with penalties for violations.

- Voter Awareness – Civil society campaigns and public disclosure of candidate records can empower voters to make informed choices.

- State Capacity – Strengthening law enforcement and reducing reliance on “muscle power” will make clean candidates more competitive.

Conclusion

The criminalisation of politics is not merely a legal or electoral issue but a crisis of democratic legitimacy. With nearly one-third of legislators facing serious charges, India risks normalising the presence of alleged criminals in the highest law-making bodies. Urgent institutional, legal, and political reforms are essential to reverse this trend and safeguard the constitutional promise of “purity of elections” and the rule of law.

Nari Shakti and India’s Economic Transformation

- 27 Aug 2025

In News:

Women’s participation in India’s workforce has witnessed a remarkable turnaround in recent years, emerging as a cornerstone of the country’s economic transformation and a critical driver for the vision of Viksit Bharat 2047.

Data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) shows that the female workforce participation rate (WPR) nearly doubled from 22% in 2017-18 to 40.3% in 2023-24, while the unemployment rate (UR) fell from 5.6% to 3.2% during the same period. This trend reflects not only improved economic opportunities but also the success of multiple policy interventions promoting gender-inclusive growth.

Rising Participation Across Sectors

The surge in women’s employment has been particularly pronounced in rural India, with a 96% rise in female employment, compared to 43% in urban areas. Importantly, self-employment among women grew from 51.9% to 67.4%, showcasing the increasing entrepreneurial orientation of India’s female workforce. Formal employment has also expanded, with 1.56 crore women joining the formal workforce in the last seven years as per EPFO payroll data. Additionally, over 16.6 crore women workers have registered on the e-Shram portal, providing them access to social security schemes.

Education, Employability, and Skills

Employability of women has improved significantly. Reports show that employability among female graduates rose from 42% in 2013 to 47.5% in 2024, while women with postgraduate education saw their WPR increase from 34.5% to 40% between 2017 and 2024. The India Skills Report 2025 projects that more than half of Indian graduates will be globally employable, marking a substantial improvement in skill readiness.

Policy Push for Women-Led Development

Government initiatives have been central to this transformation. The gender budget increased by 429% in the last decade, reaching ?4.49 lakh crore in FY 2025-26, supporting more than 70 central schemes and 400 state-level initiatives targeted at female entrepreneurship and welfare.

Flagship programmes like Startup India have created a thriving ecosystem where nearly half of DPIIT-registered startups have at least one-woman director. Schemes such as PM Mudra Yojana (with women receiving 68% of 35.38 crore loans worth ?14.72 lakh crore) and PM SVANidhi (where 44% of beneficiaries are women) have provided critical financial inclusion. Complementary initiatives like Namo Drone Didi, Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana–NRLM, and the Lakhpati Didi scheme are equipping women with resources to become economically self-reliant.

Women-Led MSMEs and Job Creation

The rise of women-led MSMEs further reflects this shift. Their number almost doubled from 1 crore in 2010-11 to 1.92 crore in 2023-24, generating 89 lakh additional jobs for women between FY21–FY23. The share of women-owned establishments grew from 17.4% to 26.2% in the same period. This expansion highlights the growing role of women as both job creators and drivers of inclusive growth.

Towards Viksit Bharat 2047

Women are no longer seen as mere beneficiaries of welfare schemes but as leaders of India’s growth story. From rural entrepreneurs to corporate directors, their contributions are reshaping the economy. Achieving the vision of 70% women workforce participation by 2047 is now integral to India’s developmental roadmap.

Conclusion

India is undergoing a paradigm shift from women’s development to women-led development. The surge in women’s employment, financial inclusion, and entrepreneurship reflects both a social transformation and an economic imperative. As Nari Shakti takes centre stage, empowering women through education, skills, and supportive policies will be crucial for India to achieve inclusive and sustainable growth on its path to Viksit Bharat.

Kerala: India’s First Fully Digitally Literate State

- 26 Aug 2025

In News:

Kerala has become the first fully digitally literate state in India, marking a historic milestone in bridging the digital divide. The achievement follows the successful completion of Phase I of the Digi Kerala project, a grassroots initiative aimed at equipping citizens with essential digital skills.

Origins of the Digital Literacy Movement

Kerala’s digital literacy journey began with the Akshaya Project in 2002, launched by President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, which aimed to make at least one member of every family digitally literate.

The recent drive was inspired by the Digi Pullampara initiative (2021) in Thiruvananthapuram, where local officials trained daily wage labourers and MGNREGS workers in basic smartphone-based services to prevent loss of wages due to long queues at banks. The success of Pullampara, which became the state’s first fully digitally literate panchayat, laid the foundation for statewide expansion.

Survey and Training Model

The programme followed a mass literacy campaign model reminiscent of Kerala’s 1980s literacy drive. Surveys covered 1.51 crore individuals across 83.45 lakh households, identifying 21.88 lakh digitally illiterate persons. Of these, 21.87 lakh (99.98%) successfully completed training and evaluation.

Training included 15 basic digital tasks such as making voice/video calls, using WhatsApp, accessing e-governance platforms, and conducting digital transactions. Volunteers—drawn from NSS units, Kudumbashree groups, SC/ST promoters, and libraries—delivered training at worksites, neighbourhood groups, and homes, ensuring inclusivity. Evaluations required participants to perform at least six out of the 15 tasks, with retraining provided where necessary.

Inclusivity and Grassroots Orientation

Unlike the National Digital Literacy Mission (NDLM) and Digital Saksharta Abhiyan (DISHA), which capped training at 60 years of age, Kerala’s programme included all age groups—even centenarians. Data shows 15,221 trainees above 90 years, and over 7.77 lakh between 60–75 years benefitted. Women (13 lakh), men (8 lakh), and 1,644 transgender persons also participated, showcasing inclusivity.

The programme also targeted marginalized communities and homemakers, ensuring that digital literacy did not remain confined to urban or privileged groups.

Integration with Kerala’s Digital Ecosystem

Kerala’s digital literacy drive is not a standalone initiative but part of a larger ecosystem:

- Kerala Fibre Optic Network (KFON): Provides universal internet access, including free connections to BPL families.

- K-SMART (Kerala Solutions for Managing Administrative Reformation and Transformation): Integrates all local self-government services onto a single digital platform.

- Digi Kerala 2.0: Expands the mission beyond basic literacy to include cyber fraud awareness, misinformation detection, and advanced e-governance training.

This smartphone-centric approach reflects ground realities, where mobile phones are the most accessible digital tool for citizens.

National Context

Digital literacy in India remains limited: only 38% households are digitally literate (61% in urban, 25% in rural areas). Past initiatives like NDLM and DISHA trained over 53 lakh people, while PMGDISHA (Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyan) has trained 6.39 crore individuals till March 2024. Kerala’s model stands out for its grassroots orientation, inclusivity, and integration with governance.

Significance

- Governance & Transparency: Enhances access to schemes like Ayushman Bharat, PM-Kisan, and Jan Dhan, while enabling online grievance redressal and RTI filing.

- Socio-Economic Empowerment: Equips women, elderly, and marginalized groups with livelihood-relevant skills.

- Disaster Resilience: Ensures continuity of education, services, and financial transactions during crises such as pandemics.

- Scalable Model: Provides a blueprint for other states under the Digital India mission, focusing not only on infrastructure but also on citizen capacity.

Conclusion

Kerala’s declaration as the first fully digitally literate state represents more than a symbolic achievement; it reflects a transformative model of participatory governance, inclusivity, and socio-economic empowerment. By bridging the last-mile digital divide, Kerala positions itself as a leader in India’s march towards a digitally empowered society.

India–China Relations

- 25 Aug 2025

In News:

The recent visit of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to New Delhi marked the first ministerial-level engagement from China since India and China agreed in October 2024 to complete disengagement at the border. Wang, meeting Prime Minister Narendra Modi, acknowledged that bilateral relations had experienced “ups and downs” and emphasised learning from past experiences. He urged that India and China view each other as partners rather than adversaries, signalling cautious attempts at resetting ties.

Historical Context

Bilateral optimism peaked in October 2019, during the second informal summit between PM Modi and President Xi Jinping at Mahabalipuram. However, eight months later, the Galwan Valley clash in eastern Ladakh resulted in 20 Indian and at least four Chinese casualties, triggering a rupture in relations. Both sides amassed 50,000–60,000 troops along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), leading to a prolonged standoff with frequent confrontations and infrastructure build-ups. Partial disengagement occurred in subsequent years, but the situation remained tense until mid-2024.

The 2024 disengagement agreement at remaining flashpoints in Depsang and Demchok, followed by a Modi–Xi meeting in Kazan, paved the way for a diplomatic thaw. Since then, exchanges at the levels of External Affairs, Defence, and National Security have contributed to restoring dialogue and confidence.

Twin-Track Strategy

India and China have revived the dual-track approach, pursuing border management and broader bilateral cooperation simultaneously. Key mechanisms under the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination (WMCC) include:

- An Expert Group to explore early harvest options in boundary delimitation

- A Working Group for effective border management to maintain peace and tranquillity

- Expansion of General-Level Mechanisms to include Eastern and Middle sectors

This strategy ensures that border issues do not obstruct the development of bilateral ties, while also recognising the need for a political perspective in settling boundary disputes.

Bilateral Cooperation

In the economic and connectivity domain, both sides agreed to:

- Resume direct flights and facilitate visas for tourists, businesses, and media

- Reopen border trade at Lipulekh Pass, Shipki La Pass, and Nathu La Pass

- Promote trade and investment flows through concrete measures

In the water resources sector, China committed to sharing hydrological information on trans-border rivers during emergencies on humanitarian grounds. The Kailash Mansarovar Yatra has resumed, reflecting thawing people-to-people exchanges.

Trust Deficit and Security Concerns

Despite progress, several issues continue to hinder trust:

- Repeated Chinese incursions (Depsang 2013, Chumar 2014, Doklam 2017, and ongoing standoffs)

- Continued deployment of over 50,000 troops in eastern Ladakh

- China–Pakistan military cooperation, including weapon and intelligence support

- Potential risks from China’s mega dam on the YarlungTsangpo (Brahmaputra) affecting downstream states

- Concerns regarding cross-border terrorism and China’s export restrictions on rare earths, fertilisers, and industrial equipment

Strategic Context

The recent thaw also comes amid shifting global dynamics, including strained India–US ties, US tariffs on Indian imports, and broader geopolitical competition. Both India and China aim to maintain stability, enhance economic cooperation, and pursue a multipolar Asia. However, sustainable rapprochement depends on Beijing addressing Indian concerns on security, water, and economic vulnerabilities, alongside constructive engagement on the border.

Migrant Disenfranchisement in India: A Democratic Challenge

- 24 Aug 2025

In News:

India, the world’s largest democracy, faces a silent yet critical challenge: the systematic disenfranchisement of internal migrants. Recent reports indicate that during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of Bihar’s electoral rolls, nearly 3.5 million voters—about 4.4% of the state’s electorate—were removed. Most affected are migrant workers who were absent during house-to-house verification and subsequently labelled as “permanently migrated,” effectively losing the right to vote both at their home and destination states. This development underscores a structural weakness in India’s electoral system and highlights the democratic deficit faced by mobile citizens.

Understanding Migrant Disenfranchisement

Migrant disenfranchisement occurs when workers are excluded from voting due to absence from their home constituencies and lack of registration in destination states. This results in a “political limbo,” particularly for circular and split-family migrants, who move seasonally for economic survival. Bihar alone has around 7 million annual out-migrants, many of whom live in rented accommodations, slums, or temporary worksites, often lacking the documentation required for voter registration.

Legal Framework and Safeguards

The Representation of the People Acts, 1950 & 1951, guarantees citizens the right to be enrolled in their ordinary residence constituency. ERONET facilitates continuous updating of electoral rolls, and the Election Commission of India (ECI) has proposed portability measures such as “One Nation, One Voter ID,” though these remain largely unimplemented. Proxy voting exists for overseas Indians but does not extend to internal migrants. Civil society initiatives, including surveys in Kerala, have highlighted gaps in voter registration and access for mobile populations.

Structural Causes of Disenfranchisement

- Sedentary Electoral Framework: Voter registration is tied to fixed residence and physical verification, disadvantaging migrants in transient living conditions.

- Circular and Split-Family Migration: Seasonal migration is often misread as permanent relocation, prompting administrative deletion from rolls.

- Administrative and Social Barriers: Migrants face bureaucratic hurdles, digital illiteracy, and social exclusion, while host states may discourage enrolment due to perceived political consequences.

- Regionalism and Sub-Nationalism: Migrants are frequently viewed as outsiders, and domicile norms for jobs can restrict political participation.

Consequences

Disenfranchisement deepens inequalities and disproportionately affects poor, seasonal, and vulnerable populations, including women near border areas. Bihar’s average voter turnout (53.2%) lags behind Gujarat (66.4%) and Karnataka (70.7%), reflecting the systemic exclusion of mobile citizens. The result is a two-tier democracy where the economically marginalized are politically voiceless.

Way Forward

- Portable Voter Identity: Develop Aadhaar-linked, mobile electoral IDs enabling voting across home and work constituencies, with privacy safeguards.

- Cross-State Coordination: EC should implement cross-verification before deletion and enable temporary voter registration for seasonal migrants.

- Civil Society Outreach: Panchayats and NGOs can facilitate re-enrolment campaigns, replicating Kerala’s successful survey models.

- Policy Harmonisation: Align electoral reforms with labour codes and welfare portability, recognising circular migration as an economic reality.

Conclusion

India’s democracy depends on the participation of all citizens, including migrants whose remittances underpin state economies. Without urgent reforms to ensure portable voter rights, inter-state coordination, and inclusive outreach, millions risk losing their political voice. Addressing migrant disenfranchisement is not merely an administrative task but a fundamental imperative for a representative and inclusive democracy.

Constitution (130th Amendment) Bill, 2025

- 23 Aug 2025

In News:

- The Constitution (One Hundred and Thirtieth Amendment) Bill, 2025, represents a significant step in strengthening constitutional morality and accountability of those holding high executive offices.

- It seeks to amend Articles 75, 164, and 239AA to provide for the automatic removal of the Prime Minister, Chief Ministers, and Ministers in the Union and state governments, if they remain under judicial custody for a prolonged period on charges of serious criminal offences.

- The Bill also extends similar provisions to Union Territories, including Delhi, Puducherry, and Jammu & Kashmir, through amendments in relevant legislations.

Key Provisions of the Bill

- Grounds for Removal:Applicable when a Minister is accused of an offence punishable with imprisonment of five years or more and has been in custody for 30 consecutive days.

- Procedure:

- At the Union level, the President must remove a Minister on the advice of the Prime Minister by the 31st day.

- At the state level, Governors act on the advice of Chief Ministers.

- In Delhi, the President acts on the Chief Minister’s advice.

- For the Prime Minister or Chief Minister, resignation is mandatory on the 31st day of custody; otherwise, their office will stand vacated automatically.

- Reappointment:The Bill does not bar reappointment after release from custody, ensuring due process for those acquitted.

Rationale and Objectives

- Constitutional Morality: Upholding values of integrity in governance and preventing the spectacle of governments being run from prisons.

- Public Trust: Protecting the legitimacy of the executive by ensuring that leaders under grave suspicion cannot continue in office.

- Good Governance: Preventing misuse of official machinery by incarcerated Ministers.

The Statement of Objects and Reasons highlights that the Bill aims to keep executive positions free from “any ray of suspicion,” thereby strengthening public confidence in democratic institutions.

Challenges and Concerns

- Opposition’s Objections: Concerns about misuse of investigative agencies and politically motivated arrests have been raised. Critics argue that automatic disqualification on custody, without conviction, may undermine the presumption of innocence.

- Judicial Safeguards: The reliance on timely judicial intervention (bail within 30 days) assumes speedy functioning of courts, which may not always be realistic.

- Federal Sensitivities: Extending the provision to Union Territories, particularly Delhi and Jammu & Kashmir, may invite political contestation.

Significance

The 130th Amendment Bill underscores India’s evolving constitutional morality by mandating that executive authority cannot coexist with criminal custody. By including the Prime Minister within its scope, the Bill strengthens democratic accountability, contrasting sharply with earlier attempts at immunity. If passed, it will create a robust ethical standard for public office, ensuring that governance is not conducted under the shadow of criminality, while allowing reappointment post-exoneration to balance fairness.

In essence, the Bill reflects an effort to reconcile democratic legitimacy, public morality, and constitutional governance, thereby reinforcing citizens’ faith in the integrity of the Indian executive.

Why India needs a national space law urgently

- 22 Aug 2025

In News:

India’s space programme has made remarkable strides in recent years, with missions such as Chandrayaan-3, the upcoming Gaganyaan human spaceflight, and plans for the Bharat Antariksh Station. Alongside, private participation in launch services, satellite communication, and space-based applications has grown significantly. However, despite being a signatory to key international treaties like the Outer Space Treaty (OST) 1967, India still lacks a comprehensive national space legislation. This gap creates uncertainty for private enterprises, investors, and regulators, making a space law an urgent necessity.

International Context and Treaty Obligations

The OST of 1967 provides foundational principles:

- Outer space as the common heritage of mankind with no claims of sovereignty.

- Activities limited to peaceful purposes and free scientific exploration.

- State responsibility for activities conducted by both government and non-government actors.

- Liability of states for damage caused by space objects launched from their territory.

While India is bound by these obligations, the treaty is not self-executing. National legislation is required to translate these commitments into enforceable domestic rules. Many countries such as the U.S., Luxembourg, Japan, and UAE have enacted laws clarifying ownership, licensing, and liability frameworks, thereby attracting global investments in their space sectors.

India’s Current Approach

India has followed an incremental strategy, relying on policies and guidelines rather than legislation:

- Indian Space Policy, 2023 → opens space activities to private players.

- IN-SPACe Norms and Guidelines, 2024 → provides authorization mechanisms.

- Catalogue of Indian Standards for Space Industry, 2023 → ensures safety and quality.

However, these are executive measures without statutory authority. The Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe) currently functions without legal backing, undermining its ability to act as a credible single-window regulator.

Key Challenges in the Absence of a Law

- Regulatory Fragmentation: Space activities involve multiple ministries (Defence, Telecom, Commerce, DoS), leading to duplication and delays. For instance, satellite communication projects require parallel clearances from DoT, Defence, and ISRO.

- Liability Concerns: Under OST, India is internationally liable for damages caused by private launches. Without domestic liability-sharing norms, startups face prohibitive insurance costs.

- FDI Uncertainty: India allows partial FDI in satellite manufacturing, but unclear automatic routes deter investors. Competitor nations offer liberal FDI frameworks, drawing startups away.

- Intellectual Property Issues: Ambiguity in IP ownership discourages innovation and risks talent migration to IP-friendly jurisdictions.

- Innovation Barriers: Overlapping clearances and unclear rules delay project timelines, stifling private-sector growth.

Way Forward

- Comprehensive Space Activities Law: Clearly define licensing, liability, insurance, IP rights, and dispute resolution in line with OST.

- Statutory Empowerment of IN-SPACe: Grant it legal authority as an independent single-window regulator with transparent, time-bound processes.

- Insurance Framework: Establish government-backed reinsurance pools to make liability coverage affordable for startups.

- Liberalised FDI Norms: Allow 100% FDI in satellite component manufacturing under the automatic route with safeguards for national security.

- IP and Innovation Ecosystem: Protect private patents, encourage industry–academia collaboration, and retain domestic talent.

Conclusion

India stands at a decisive moment in its space journey. The absence of a comprehensive space law risks slowing down private participation, deterring investment, and exposing the country to unmitigated liability under international law. Enacting robust legislation would not only provide clarity and predictability but also align India with global best practices, nurture its commercial space ecosystem, and position it as a trusted global leader in space governance. With India aspiring to host major international space events and expand its presence in global markets, the urgency for a national space law has never been greater.

AI-Powered Early Warning System for Elephant Conservation

- 21 Aug 2025

Introduction

Human-elephant conflict is a persistent challenge in India, particularly in regions where railway lines intersect traditional migratory routes of elephants. In response, the Tamil Nadu Forest Department, in collaboration with the railways, has pioneered an AI-enabled early warning system in the Walayar–Madukkarai forest range along the Kerala–Tamil Nadu border. This initiative, operational since February 2024, has emerged as a model for technology-driven wildlife conservation.

Background

The Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a critical biodiversity hotspot, serves as a migratory corridor for elephants moving between the Nilgiris, Sathyamangalam, and Kerala forests. However, expanding rail and road infrastructure, coupled with land-use changes and increasing human presence, has fragmented these habitats.

The Coimbatore Forest Division alone reported nearly 9,000 elephant straying incidents between 2021 and 2023. The Madukkarai range, traversed by two railway tracks through reserved forests, has been particularly vulnerable. Since 2008, 11 elephants, including calves, have died due to train collisions in this area, underscoring the urgency for preventive measures.

The AI-Powered Surveillance System

- Infrastructure: The system comprises 12 surveillance towers fitted with 24 high-resolution thermal cameras, strategically placed along a vulnerable 7-km stretch of railway track.

- Technology: Using artificial intelligence and machine learning, the cameras detect elephant presence up to 100 feet near tracks. The system is modeled on surveillance technology used by the Indian Army at border areas.

- Command Centre: Located near Walayar, it is staffed by trained forest personnel and local tribal youth. The system operates 24×7, sending real-time alerts to railway control rooms, loco pilots, and patrol teams.

- Integration with Railways: Alerts prompt loco pilots to slow down or halt trains, while forest staff guide elephants safely across or divert them through designated underpasses.

- Results: Since its commissioning, the system has facilitated over 6,500 safe elephant crossings and generated over 5,000 alerts, with zero elephant fatalities reported.

Broader Significance

- Wildlife Safety: The system ensures unhindered migratory movement of elephants, mitigating human-wildlife conflict.

- Community Involvement: Employment of tribal youth in monitoring enhances local participation in conservation.

- Judicial Oversight: The initiative aligns with the Madras High Court’s 2021 directive to minimize elephant deaths on railway tracks.

- Multi-Species Benefit: The cameras also detect human presence, reducing risks of accidents and aiding in conflict management.

Challenges and Way Forward

Elephants are highly adaptive and often circumvent traditional barriers such as trenches or solar fences, making AI-driven monitoring more reliable. However, scaling up faces challenges of financial allocation, technical expertise, and maintenance. The Tamil Nadu government has announced plans to expand the system to four more vulnerable areas including Dharmapuri and Hosur, indicating policy commitment.

To ensure long-term success:

- Similar AI-based systems should be introduced across critical elephant corridors in states like Assam, Odisha, and Karnataka.

- Railway infrastructure should integrate wildlife underpasses and overpasses with AI monitoring.

- A national-level database linking forest departments and railways could enhance coordination.

- Awareness campaigns and community engagement must complement technological solutions.

Conclusion

The AI-powered early warning system in Coimbatore division demonstrates how advanced technology, when integrated with local knowledge and institutional support, can resolve persistent conservation challenges. With elephants being a keystone species vital to ecosystem stability, such interventions are crucial to balance developmental imperatives with biodiversity conservation. Replicating and scaling up this initiative across India could significantly reduce human-elephant conflict and serve as a global model for AI-driven wildlife protection.

“Master of the Roster” Controversy: Balancing Judicial Independence & Accountability

- 20 Aug 2025

Context

A recent incident involving the Supreme Court’s censure of an Allahabad High Court judge has reignited debate about the apex court’s authority over High Courts’ internal administration—specifically, the Chief Justice’s exclusive “Master of the Roster” (MoR) power. The case, involving Justice Prashant Kumar, raised broader issues of judicial discipline, institutional autonomy, and constitutional hierarchy.

The Incident & Its Fallout

A Bench led by Justices Pardiwala and Mahadevan directed that Justice Prashant Kumar be removed from the criminal roster and paired with a senior judge after an “erroneous” judgment. This triggered objections from the Allahabad High Court, which argued it constituted a breach of its administrative autonomy. Following communications from the Chief Justice of India, the Supreme Court clarified that its ruling did not intend to infringe on the Chief Justice’s MoR powers.

Constitutional Principles at Stake

- Master of the Roster Principle:

- Entrails the exclusive right of a Chief Justice—High Court or Supreme Court—to constitute benches and allocate cases. Key precedents affirm this prerogative: State of Rajasthan v. Prakash Chand (1998), State of Rajasthan v. Devi Dayal (1959), and Mayavaram Financial Corporation (Madras HC, 1991).

- Supreme Court’s Binding Authority:

- Article 141 mandates that decisions of the Supreme Court are binding throughout India.

- Article 142 empowers the Court to issue orders necessary for “complete justice,” enabling it to take corrective measures.

- Judicial Independence vs. Oversight:

- High Courts enjoy constitutional autonomy (Art. 214), and the Supreme Court lacks superintendence over them. Yet, the integrated judiciary framework permits intervention when integrity or rule of law is at stake. In Tirupati Balaji Developers (2004), the SC described itself as the “elder brother,” not an administrative overlord.

Issues Raised

- Scope of SC Intervention: Can the Supreme Court issue administrative directives affecting a High Court Chief Justice’s roster authority?

- Judicial Discipline vs. Undermining Autonomy: How can errors be corrected without compromising institutional independence?

- Use of Article 142: Does preventive intervention under this provision set a precedent for future interventions?

- Separation within the Judiciary: Where is the line between hierarchical oversight and judicial autonomy?

In-House Mechanism vs. Public Correction

While serious misconduct among judges is typically addressed through confidential in-house procedures or through impeachment by Parliament, the Supreme Court’s public directive in open court was corrective rather than punitive. The approach—pairing the errant judge with a senior adjudicator—was meant to enhance judicial quality while signaling accountability.

Way Forward

- Define clear guidelines elucidating when the Supreme Court may legitimately intervene in High Courts’ administrative matters.

- Strengthen internal supervisory mechanisms to address judicial errors without resorting to public admonishment.

- Enhance capacity-building, mentorship, and training to minimize repeated lapses in judicial decisions.

Conclusion

The MoR principle is a foundational safeguard of judicial independence, but it does not immune the judiciary from scrutiny or intervention when errors threaten the rule of law. The Supreme Court’s constitutional powers under Article 142 enable exceptional corrective action—but such powers must be exercised judiciously to preserve institutional autonomy and public trust.

US–China Trade Truce and the Role of Agricultural Imports in Geoeconomics

- 19 Aug 2025

In News:

The United States and China, the world’s two largest economies, have extended their trade truce for another 90 days until November 10, 2025, averting a sharp escalation of tariffs. The pause keeps US duties on Chinese goods at 30% (against a threatened 145%) and Chinese tariffs on US shipments at 10% (down from an earlier 125%). This temporary reprieve reflects the complex mix of economics, politics, and strategic leverage shaping bilateral relations.

Tariffs and Negotiation Dynamics

Since his return to office, US President Donald Trump has pursued aggressive tariff measures to reduce America’s $300 billion trade deficit with China (2024), arguing that higher duties encourage domestic production and investment. Beijing retaliated with counter-tariffs and restrictions, sparking a tit-for-tat escalation that threatened global supply chains.

The extension of the truce provides space for negotiations over trade imbalances, unfair practices, national security concerns, and market access. It also underscores the challenges of balancing protectionism with the risks of inflation, uncertainty for businesses, and potential disruption to global economic stability.

China’s Leverage: Rare Earths and Agriculture

Beijing has strategically wielded two levers of influence. First, it controls the global supply chain of rare-earth elements and magnets, crucial for the US auto, aerospace, defence, and semiconductor industries. Second, it has employed its role as a major importer of agricultural commodities as a “trump card.”

US farm exports to China fell sharply from $13.1 billion (Jan–June 2024) to $6.4 billion (Jan–June 2025), continuing a downward trend from the 2022 peak of $40.7 billion. The steepest decline has been in soybean exports, dropping from $17.9 billion (2022) to just $2.5 billion (Jan–June 2025). China has redirected much of its soybean imports—74.7 million tonnes in 2024—to Brazil, Argentina, and Canada, significantly hurting American “corn belt” states and livestock producers reliant on feed crops.

Beyond soybeans, imports of US corn, sorghum, barley, cotton, beef, pork, poultry, and tree nuts such as almonds and pistachios have also contracted. This has created pressure on Trump from politically influential farm states, prompting him to publicly urge Beijing to expand soybean purchases.

Impact on the US and India

While American agricultural exports to China have fallen by 51.3% (Jan–June 2025 over 2024), those to India have surged 49.1% in the same period. India has emerged as the largest market for US tree nuts, importing over $1.1 billion in 2024, with a 42.8% year-on-year rise in early 2025. At the same time, the US has become India’s largest buyer of seafood, with frozen shrimp exports worth $1.9 billion in 2024–25.

This divergence highlights India’s growing importance in US agricultural trade, even as tariff disputes persist—Washington recently doubled duties on Indian imports to 50%, citing penalties linked to Russian oil purchases.

Broader Strategic Context

The US–China trade confrontation extends beyond tariffs and agriculture. Issues under negotiation include curbs on semiconductor exports, the role of Chinese platforms like TikTok, and energy security linked to Russian oil purchases. Beijing emphasizes “win-win cooperation,” while Washington continues to pursue coercive tools to address trade imbalances and safeguard national security.

Conclusion

The current trade truce reflects a fragile pause rather than resolution. China’s use of agriculture and rare earths as instruments of economic statecraft illustrates the growing intertwining of trade, technology, and geopolitics. For the US, balancing domestic political pressures from farmers and industries with long-term strategic objectives remains a challenge. For India, the shifting trade landscape offers both opportunities for greater market access and risks of tariff retaliation, underlining the complexity of navigating major power rivalries.

Documenting India’s Endangered Languages

- 18 Aug 2025

Context:

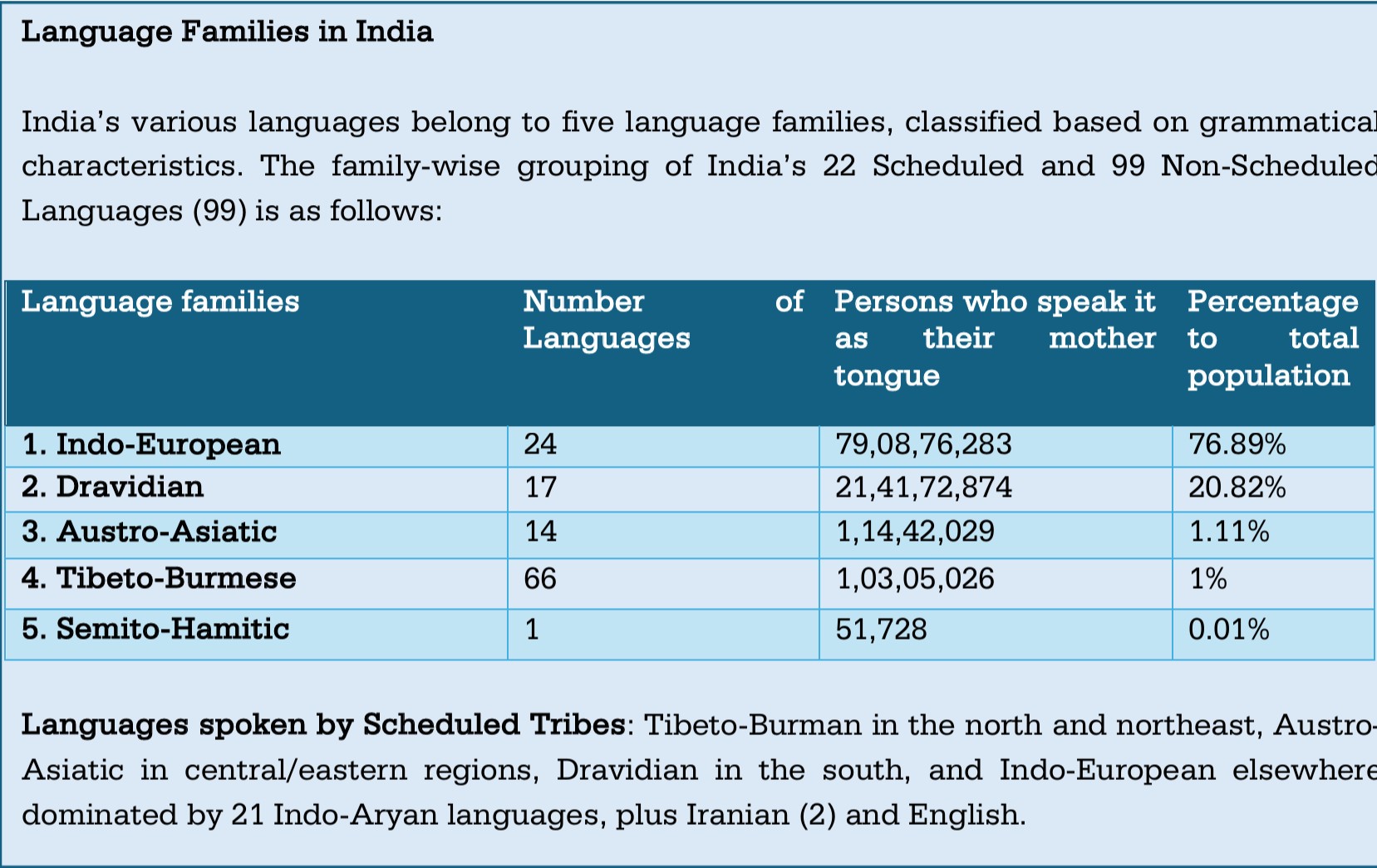

India is home to one of the world’s richest linguistic landscapes, with the 2011 Census recording over 2,800 mother tongues, of which 1,369 were classified as recognized languages. However, many languages remain vulnerable: those spoken by fewer than 10,000 people are categorized as endangered.

According to the Scheme for Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages (SPPEL) of the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL), 117 endangered languages have been identified, and efforts are underway to document nearly 500 lesser-known languages in the future.

The Case of the Toda Tribe

The Toda tribe of the Nilgiri Hills in Tamil Nadu exemplifies India’s efforts at language preservation. Toda is a proto-South Dravidian language without a native script, spoken by only a few thousand people today. Traditionally oral, it encapsulates the community’s myths, rituals, and ecological knowledge. Under SPPEL, Toda elders have collaborated with linguists to record stories, songs, and vocabulary, producing primers in the Tamil script for schoolchildren and uploading digital archives to Sanchika, CIIL’s online repository launched in 2025. This initiative not only preserves linguistic material but also strengthens cultural identity.

Government and Institutional Efforts

SPPEL employs a systematic process of recording, transcription, grammar construction, cultural documentation, and digital archiving. Advanced tools—such as high-end audio-video equipment and linguistic analysis software—are used to create bilingual dictionaries, pictorial glossaries, and ethno-linguistic profiles.

Complementary schemes also support linguistic diversity. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs, through the TRI-ECE initiative, has funded AI-based translation tools to convert Hindi/English text into tribal languages. The Ministry of Culture promotes folk and tribal arts through programs such as the National Mission for Cultural Mapping and the Rashtriya Sanskriti Mahotsavs, while the Sahitya Akademi organizes annual tribal writers’ meets. These interventions align with the National Education Policy 2020, which emphasizes multilingual education.

Global Perspective

The erosion of linguistic diversity is not unique to India. UNESCO estimates that nearly half of the world’s 7,000 languages are endangered, with the loss of each language erasing irreplaceable cultural heritage. Recognizing this, UNESCO has declared 2022–2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, urging global stakeholders to act. The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples (August 9) further highlights indigenous rights and cultural preservation.

Technology has emerged as both a challenge and a solution. While AI systems often appropriate indigenous knowledge without consent, initiatives such as New Zealand’s Te Hiku Media for M?ori and Polynesian reef conservation projects demonstrate AI’s potential for revitalization. In India, the integration of AI into language preservation efforts reflects this global trend.

Way Forward

Preserving endangered languages is critical for safeguarding traditional ecological knowledge, oral heritage, and cultural diversity. India’s multilingual character—where 22.9 crore people are bilingual and 8.6 crore are trilingual—creates opportunities for inclusive education models that protect minor languages while enabling wider communication. Community-driven documentation, AI-enabled tools, and government support can ensure continuity across generations.

As UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay has noted, “Language is what makes us human. When people’s freedom to use their language is not guaranteed, this limits their freedom of thought and expression.” For India, the preservation of endangered languages is not merely cultural—it is a matter of equity, identity, and sustainable development.

India’s Unique Genetic Legacy

- 17 Aug 2025

Context:

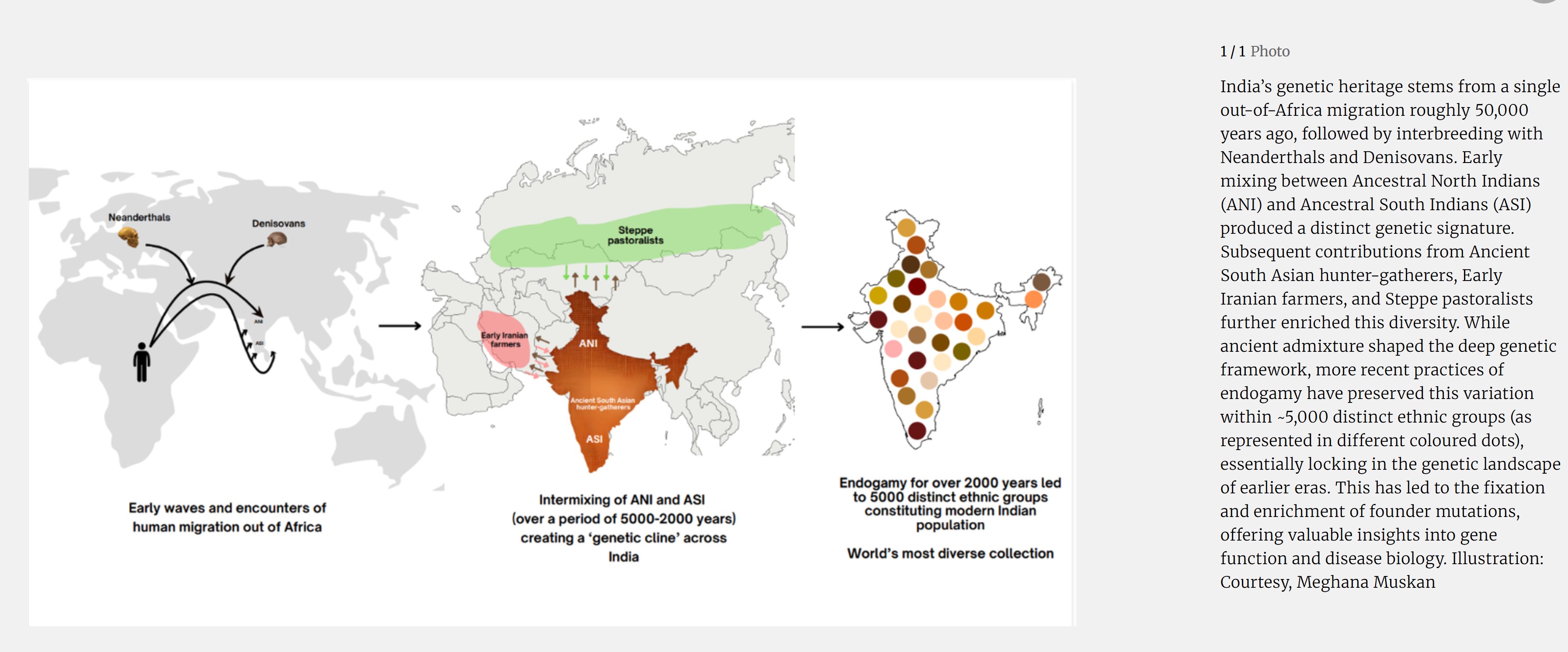

India, with a population of over 1.4 billion and nearly 5,000 distinct ethnic groups, represents one of the richest reservoirs of human genetic diversity in the world. This diversity, shaped by ancient migrations, interbreeding with archaic humans, and centuries of endogamy, makes India a living archive of evolutionary history as well as a frontier for personalised medicine.

Evolutionary Roots and Genetic Mixing

The genetic history of Indians can be traced to a single out-of-Africa migration around 50,000 years ago. These early settlers interbred with archaic humans such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, leaving modern populations with 1–2% of archaic DNA. Some of these variants continue to influence present-day biology—for example, Denisovan genes aiding Tibetan high-altitude adaptation and Neanderthal genes linked to immune responses and even COVID-19 severity.

Within India, genetic blending between Ancestral North Indians (ANI) and Ancestral South Indians (ASI) created a distinct genetic signature. Later contributions from ancient hunter-gatherers, early Iranian farmers, and Steppe pastoralists added further complexity. This intricate demographic history is preserved in the unique genomic architecture of Indian populations, which remains poorly represented in global studies such as the UK Biobank or 1000 Genomes Project.

Endogamy and Disease Patterns

A distinctive feature of Indian society has been endogamy, or marrying within one’s community. While this preserved ancient traits, it also intensified genetic relatedness and strengthened “founder effects.” As a result, many rare recessive diseases occur at unusually high frequencies within specific groups.

For instance, the Vysya community shows a hundred-fold higher prevalence of butyrylcholinesterase deficiency, while other groups carry unique mutations linked to progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia or congenital disorders. Large-scale genome sequencing of ~2,700 Indians revealed that each person, on average, has at least one fourth-degree relative, underscoring the depth of relatedness. More than 1.6 lakh previously unreported variants have been identified, many linked to neurological, metabolic, and cardiovascular conditions.

Scientific and Healthcare Potential

This diversity is not merely of anthropological interest but holds transformative implications for medicine. Each Indian community functions as a natural genetic laboratory, preserving rare variants that allow scientists to study gene functions without laboratory-induced mutations. This provides an unprecedented opportunity to advance precision medicine, drug discovery, and disease prevention strategies tailored to Indian populations.

The Genome India Project, which has already sequenced 10,000 genomes, is a milestone towards this goal. Scaling it to millions of individuals, coupled with the creation of a national biobank on the lines of the UK Biobank, could position India as a global hub for genome-driven healthcare and innovation.

Challenges and Way Forward

Despite these opportunities, India faces major gaps. Representation in international genomic databases remains minimal. The risks of genetic discrimination and privacy breaches call for a robust ethical and legal framework. Moreover, integrating genetic screening into public health policy requires awareness campaigns, trained professionals, and equitable access to avoid deepening existing inequalities.

Conclusion

India’s genetic mosaic is both a scientific treasure and a public health imperative. By scaling up sequencing, building inclusive biobanks, and embedding genomics into healthcare policy, India can simultaneously improve disease management, reduce the burden of rare disorders, and emerge as a leader in global genomics research. With foresight, investment, and ethical safeguards, India’s genetic legacy can be harnessed to transform healthcare and strengthen its knowledge economy.

Judicial Pendency in India

- 14 Aug 2025

In News:

The Indian judiciary today faces an unprecedented backlog of over 5 crore pending cases across all levels—Supreme Court, High Courts, and District Courts. This crisis not only weakens the justice delivery system but also erodes citizen trust in governance and constitutional values.

Magnitude of Pendency

As of mid-2025:

- District Courts account for nearly 90% of pendency, with 4.6 crore+ cases.

- High Courts face a backlog of 63.3 lakh+ cases.

- The Supreme Court has 86,700+ pending cases.

A notable disparity exists between criminal and civil case disposal. While 85.3% of criminal cases in High Courts are resolved within a year, only 38.7% of civil cases in district courts meet this timeline. Alarmingly, nearly 20% of civil cases remain unresolved for more than five years. The Chief Justice of India has flagged the issue of excessive caution in granting bail as one contributor to this delay.

Causes of Judicial Pendency

- Low Judge-Population Ratio: With only 15 judges per 10 lakh population, India lags behind the Law Commission’s recommendation of 50 judges per million. Though women constitute 38% of lower judiciary, their representation in High Courts remains at just 14%.

- Adjournment Culture: Excessive adjournments worsen pendency. A Delhi High Court study found 70% of delayed cases involved over three adjournments, leading to the infamous “tareek pe tareek” phenomenon.

- Underutilized ADR: Mediation, arbitration, and conciliation are not fully tapped despite their cost-effectiveness. Absence of comprehensive ADR performance data further hampers evaluation.

- Rising Litigation: Greater legal awareness, increasing PILs, and non-meritorious cases fuel the backlog. Notably, nearly half of pending cases involve government departments, where routine appeals prolong litigation.

- Structural Deficits: Shortage of courtrooms, staff, weak ICT systems, delays in evidence and witness availability, and lack of case management frameworks further strain judicial functioning.

Reform Initiatives

- National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms (2011): Enhancing access and efficiency.

- e-Courts Project: Paperless filing, virtual hearings, faster processing.

- Fast Track Special Courts: Speedy trials for specific offences.

- Tele-Law & Nyaya Bandhu: Expanding legal aid through technology and pro bono services.

- Appointments: Between 2014–2024, 62 Supreme Court and 976 High Court judges were appointed; district courts saw strength rise from 19,518 to 25,609.

Lok Adalats remain highly effective, having disposed of 27.5 crore cases between 2021–2025.

Strengthening the Judicial System

- Capacity Expansion: Raise judge strength to 50 per million, expedite appointments, enhance collegium transparency, and establish specialized courts.

- Infrastructure & Technology: Create a National Judicial Infrastructure Authority, expand e-Courts, use AI for case clustering and tracking, and adopt tools like FASTER for electronic transmission of orders.

- Procedural Reforms: Enforce strict limits on adjournments, adopt summary trials, pre-trial conferences, and time-bound hearings.

- Promote ADR: Effective implementation of the Mediation Act, 2023, expansion of arbitration centres, and scaling up of Lok Adalats can significantly reduce court burden.

- Legal Access: Strengthen Tele-Law, legal aid clinics, and NALSA’s outreach for marginalized groups.

Conclusion

India’s judiciary stands at a crossroads. The sheer volume of pending cases undermines the principle that “justice delayed is justice denied.” Addressing judicial vacancies, modernizing infrastructure, embracing technology, and institutionalizing ADR mechanisms are no longer policy options but constitutional imperatives. Strengthening the justice delivery system is vital not only for effective governance but also for sustaining the rule of law and democratic trust.

ESG Oversight and the Challenge of Greenwashing in India

- 13 Aug 2025

Introduction

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices are increasingly shaping corporate accountability and sustainable development worldwide. In India, where environmental degradation, social inequality, and governance failures remain pressing challenges, ESG assumes even greater significance. Recognising rising risks of greenwashing—the practice of making false or exaggerated sustainability claims—a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance has recently recommended the establishment of a dedicated ESG oversight body under the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA).

Understanding ESG

- Environmental: Evaluates a company’s impact on the climate, energy use, waste management, and biodiversity.

- Social: Measures inclusivity, labour standards, community engagement, and equitable growth.

- Governance: Focuses on transparency, ethical decision-making, compliance, and protection of shareholder interests.

In India, ESG is critical because of:

- Climate vulnerability: India experienced 322 extreme weather days in 2024 (CSE), making sustainability practices urgent.

- Social concerns: Persistent poverty and inequality require businesses to prioritise inclusivity.

- Governance needs: Strong corporate ethics help attract investment and build long-term trust.

Key Recommendations of the Standing Committee

- ESG Oversight Authority: A specialised body under MCA to verify sustainability claims, detect fraud, and design sector-specific ESG guidelines.

- Strengthening Legal Mandate: Amendments to the Companies Act, 2013 to embed ESG responsibilities into directors’ duties, making sustainability a core element of business strategy.

- Support for MSMEs: Providing frameworks and guidance to help small enterprises adopt ESG without excessive compliance burden.

- Deterrence Measures: Faster penalties for false claims to curb greenwashing.

- Strengthening Institutions: Empowering SFIO and NFRA to detect financial crimes linked with ESG misreporting.

- CSR Transparency: Better monitoring to ensure Corporate Social Responsibility efforts are genuine and impactful.

India’s ESG Initiatives

- SEBI’s BRSR Framework: Mandates top 1,000 listed companies to disclose ESG performance, aligned with international norms like GRI and SASB.

- CSR Mandate (Companies Act, 2013): Encourages companies to invest in social and environmental causes.

- Green Rating Project (CSE): Rates industries on environmental performance.

The Challenge of Greenwashing

Greenwashing undermines ESG credibility by misleading consumers and investors. It often involves vague labels (“eco-friendly,” “natural”), token CSR activities, or misuse of traditional systems like Ayurveda to project sustainability without genuine practices.

Factors driving greenwashing in India

- Eco-consumerism: Rising demand for sustainable goods, especially among youth.

- Weak enforcement: Non-mandatory standards like BIS Eco-Mark limit accountability.

- Fragmented regulations: ESG rules spread across multiple agencies, creating compliance gaps.

- Cultural exploitation: Misuse of heritage-based terms for marketing.

- CSR marketing: Highlighting symbolic actions while continuing harmful operations.

Regulatory Safeguards

- Consumer Protection Act, 2019: Central Consumer Protection Authority can penalise misleading environmental claims.

- ASCI Guidelines: Ensure environmental claims in advertising are evidence-based.

- Plastic Waste Management Rules: Aim to regulate reduction claims, though gaps remain.

Conclusion

The rise of ESG reflects India’s journey towards balancing economic growth with sustainability and ethics. However, greenwashing threatens this transition, diluting genuine efforts. The Parliamentary Committee’s recommendation for a centralised ESG oversight authority is timely, offering a pathway to ensure accountability, strengthen investor confidence, and align India’s corporate governance with global sustainability standards.

For India, integrating ESG into the corporate ethos is not merely regulatory compliance—it is a strategic imperative for long-term resilience, social equity, and climate security.

Commemoration of 80 Years Since Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- 11 Aug 2025

In News:

August 2025 marks 80 years since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima (6 August) and Nagasaki (9 August) in 1945, events that not only ended World War II but heralded the beginning of the nuclear age. These bombings remain the only wartime use of nuclear weapons, claiming over 150,000 to 246,000 lives, predominantly civilians, by the end of 1945.

From Stalemate to Nuclear Intervention

- Pearl Harbor (7 December 1941) instigated U.S. entry into WWII and initiated several brutal battles across the Pacific—the likes of Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa—underscoring the mounting cost of a ground invasion of Japan.

- Japan’s continued resistance despite devastating firebombing campaigns (notably Tokyo in March 1945) and the Potsdam Declaration (July 1945) demanding surrender set the stage for nuclear escalation.

- The Manhattan Project, secret since 1942, culminated in the Trinity test (16 July 1945), proving the atomic bomb's feasibility.

The Bombings Unfold

- Hiroshima (6 August 1945): ‘Little Boy’, a uranium-fission bomb dropped by the B-29 Enola Gay, caused roughly 80,000 immediate deaths; total fatalities reached ~140,000 by end of that year.

- Nagasaki (9 August 1945): ‘Fat Man’, a plutonium-fueled implosion device, dropped amid weather delays on Kokura, killed about 40,000 immediately—totaling ~70,000 by year-end.

Motives Behind the Bombing

- Avoiding invasion casualties: Operation Downfall, the planned invasion, projected massive Allied and Japanese losses.

- Psychological pressure: The bomb's unprecedented devastation aimed to force Japan's surrender.

- Geo-strategic signaling: The bombings demonstrated U.S. might—curbing Soviet advances—and launched the world into a new Cold War dynamic.

- Domestic justification: Following decades and billions invested into the Manhattan Project, prevailing sentiment demanded usage for war-ending impact.

The Aftermath and Long-Term Impact

- Japan surrendered on 14 August 1945, formalizing it on 2 September aboard USS Missouri.

- The nuclear age dawned, introducing doctrines like Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) and fueling a global arms race visible in treaties and strategic postures to this day.

- Institutions like the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) were later established as symbols for peace and reminders of nuclear risks.

Legacy: Memory and Contemporary Discourse

- Each year, Hiroshima and Nagasaki hold solemn ceremonies—featuring lanterns, peace pledges, and remembrance—to honour victims and renew calls for nuclear disarmament.

- Survivors (hibakusha) testimonials, such as shared during the 80th anniversary, continue to fuel global nuclear abolition movements.

- Contemporary debates persist: while some argue the bombings were a necessary evil to hasten peace, others denounce them as moral travesties — a discourse still evolving with new declassified archival evidence.

Conclusion

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were more than wartime events—they ushered in a nuclear epoch marked by existential security threats, ideological competition, and ethical dilemmas. As the world reflects on this 80th anniversary, it must balance historical comprehension with vigilant advocacy for disarmament, remembering that nuclear weapons’ destructive legacy persists, as relevant and grave as ever.

Medical Tourism in India

- 10 Aug 2025

In News:

India has emerged as one of the leading destinations for medical tourism, attracting foreign patients due to its cost-effective treatments, advanced healthcare infrastructure, and traditional wellness systems. The surge in foreign tourist arrivals (FTAs) for medical purposes highlights the sector’s growing role in India’s economy, diplomacy, and healthcare landscape.

Current Trends in Medical Tourism

- Between January–April 2025, India recorded 1,31,856 medical FTAs, accounting for 4.1% of total FTAs in this period.

- In 2024, medical FTAs stood at 6.44 lakh, a sharp increase from 1.82 lakh in 2020, indicating robust growth despite global pandemic disruptions.

- Top source countries (2024):

- Bangladesh – 4.82 lakh arrivals (largest contributor).

- Iraq – 32,008 arrivals.

- Somalia – 11,717 arrivals.

- Oman – 10,431 arrivals.

- Uzbekistan – 8,921 arrivals.

This surge reflects both India’s healthcare competitiveness and rising global demand for affordable, high-quality treatment.

Why India attracts Medical Tourists

- Affordability & Quality – Advanced medical procedures at a fraction of Western costs.

- Specialised Expertise – Strong presence in cardiology, orthopaedics, oncology, organ transplants, and IVF.

- Traditional Wellness – Ayurveda, Yoga, and naturopathy complement allopathic care, attracting wellness tourists.

- Regulatory Support – Extension of e-Medical visa and attendant visa facilities to 171 countries, easing travel for patients.

- Integrated Ecosystem – Hospitals, facilitators, hotels, airlines, and regulatory bodies work together under the ‘Heal in India’ initiative.

Government Initiatives

- National Efforts:

- ‘Heal in India’ campaign (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare) promoting India as a global healthcare hub.

- Encouraging public-private partnerships (PPP) to expand hospital capacity, improve service delivery, and enhance medical infrastructure.

- Branding and showcasing India’s medical expertise at international platforms.

- Visa Facilitation:E-medical visa/e-medical attendant visa for 171 countries to smoothen entry of international patients.

- State-level Initiatives (Case Study: Gujarat):

- Registration of wellness retreats on official tourism websites.

- Participation in global health & wellness exhibitions, seminars, and conferences.

- Familiarisation trips (FAM) for industry stakeholders to promote wellness centres.

- Training paramedical staff to improve quality of care for foreign patients.

- Use of social media and global outreach to project Gujarat’s health infrastructure and wellness potential.

Economic & Strategic Significance

- Foreign Exchange Earnings – Growing inflows from high-value medical travellers.

- Employment Generation – Creation of jobs in healthcare, tourism, and allied sectors.

- Soft Power & Health Diplomacy – India’s outreach in medical care strengthens its global image and fosters bilateral goodwill, especially with neighbouring and developing countries.

- Regional Leadership – With Bangladesh, Iraq, and African nations as major contributors, medical tourism strengthens India’s role as a regional healthcare hub.

Challenges

- Uneven distribution of healthcare infrastructure across states.

- Regulatory concerns regarding quality assurance in smaller hospitals and clinics.

- High dependence on a few source countries.

- Competition from emerging medical tourism destinations like Thailand, Singapore, and Turkey.

Way Forward

- Standardisation& Accreditation – Enforcing global quality standards across hospitals to build trust.

- Digital Integration – Expanding telemedicine, AI-based diagnostics, and digital health records for seamless cross-border care.

- Wellness Tourism Synergy – Combining allopathic treatments with Ayush-based wellness offerings.

- Infrastructure Development – Strengthening airports, medical hubs, and hospitality sectors near healthcare clusters.

- Diversification of Source Countries – Targeting Africa, Middle East, and Latin America for expansion.

Conclusion

India’s medical tourism sector is a sunrise industry, merging healthcare excellence with tourism potential. With over 1.3 lakh medical FTAs in early 2025 alone, the sector underscores India’s strength as a global healthcare destination. By addressing challenges and scaling up initiatives like ‘Heal in India’, India can transform medical tourism into a key pillar of economic growth, soft power, and international diplomacy.

National Handloom Day and the Legacy of the Swadeshi Movement

- 09 Aug 2025

In News:

Every year on 7th August, India celebrates National Handloom Day, commemorating the launch of the Swadeshi Movement (1905), which emerged as a response to the Partition of Bengal by Lord Curzon. The movement marked a turning point in India’s struggle for self-reliance by promoting indigenous industries, especially handlooms, as an instrument of economic resistance against colonial rule.

Historical Background: Swadeshi Movement

The Calcutta Townhall meeting of 1905 formally initiated the Swadeshi Movement. Its key methods included:

- Boycott of British goods like Manchester cloth and Liverpool salt, encouraging Indian-made products.

- National Education, leading to the founding of institutions such as Bengal National College and Bengal Technical Institute.

- Formation of Samitis, e.g., Swadesh Bandhab Samiti led by Ashwini Kumar Dutta.

- Use of festivals and cultural symbols, such as Raksha Bandhan by Rabindranath Tagore, to foster unity.

- Social reform agenda, linking Atma Shakti (self-strength) with campaigns against caste oppression, dowry, and alcoholism.

The movement evolved from a moderate phase led by Surendranath Banerjee to a radical phase under Lal-Bal-Pal, demanding Swaraj through boycott, passive resistance, and mass mobilization.

Impact

- Political: The 1906 INC session under DadabhaiNaoroji declared Swaraj as the ultimate goal. However, ideological differences caused the Surat split (1907).