UNESCO Global Education Report 2025

- 29 Oct 2025

In News:

The UNESCO Global Education Report 2025 offers a critical evaluation of global progress toward gender equality in education, exposing persistent disparities despite decades of international commitments. Although substantial improvements have been recorded since the 1995 Beijing Declaration, an alarming 133 million girls worldwide remain out of school, signalling unfinished global obligations.

Progress Achieved

- The report highlights significant gains in enrolment and access. Compared to 1995, 91 million more girls are in primary school and 136 million more are enrolled in secondary education.

- Tertiary education has witnessed the most dramatic progress, with women's enrolment tripling from 41 million to 139 million. These trends reflect global investments in universal education programmes, gender inclusion policies, and financial support mechanisms.

Regional Variations

Despite overall progress, regional disparities persist. Central and South Asia have achieved gender parity in secondary education, demonstrating effective policy interventions. Conversely, Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania continue to lag, constrained by poverty, rural isolation, armed conflicts, and socio-cultural restrictions. In countries such as Mali and Guinea, lower secondary completion rates for girls remain below 20%, indicating severe structural inequities. In contrast, Latin America and the Caribbean show higher dropout rates among boys, underscoring region-specific challenges.

Quality and Inclusivity Deficits

The report stresses that enrolment gains alone do not translate into gender equality. Only two-thirds of countries have compulsory sexuality education at the primary level, and gender biases persist in textbooks and curricula. These embedded stereotypes perpetuate discriminatory norms and restrict girls’ aspirations and subject choices. Safety concerns—including school-related gender-based violence—further hinder learning continuity, particularly for adolescent girls.

Leadership Inequality

Although women comprise a significant proportion of the global teaching workforce, their presence in leadership positions remains limited. Only 30% of higher education leadership roles are held by women, revealing systemic barriers such as limited institutional support, leadership pipelines, and entrenched patriarchal structures. This leadership gap undermines gender-sensitive decision-making within education systems.

Economic and Social Implications

UNESCO reinforces that girls’ education is not merely a human rights imperative but an economic and socio-developmental necessity. The World Bank (2024) estimates that closing the gender gap in education could boost global GDP by $15–30 trillion, reflecting the massive economic potential of women’s participation in the workforce. Educated girls contribute to improved health outcomes, reduced poverty, enhanced labour force participation, and greater intergenerational development.

Way Forward

The report calls for gender-transformative policies—including equitable curricula, strengthened pathways for women in leadership, expanded sexuality education, safer learning environments, and evidence-based monitoring. Achieving the vision of the Beijing Declaration requires political will, sustained investments, and community-level engagement to dismantle structural barriers.

Can Rural Education Transform Migration Patterns? Reimagining Opportunities Beyond Cities

- 28 Oct 2025

In News:

Migration has been a central feature of India’s socio-economic evolution, but the growing exodus of rural youth to urban centres signals deep developmental imbalances. While migration is natural in a dynamic economy, its scale—particularly among young people—highlights failures in generating dignified rural livelihoods, aligning education with market needs, and creating resilient local ecosystems.

Understanding the Scale and Nature of Youth Migration

- Magnitude: Nearly 29% of India’s population are migrants; 89% originate from rural areas.

- Age Profile: Over half of all migrants are aged 15–25, indicating the loss of India’s most productive demographic.

- Pandemic Exposure: The 2020 Covid-19 lockdown forced 40 million workers to return home, revealing the fragility of informal urban employment.

- Gender Dynamics: Men migrate mainly for work, while 86.8% of women migrate due to marriage, reflecting persistent social norms.

- Socio-economic Profile: Higher migration rates among SC, OBC, and low-income groups show distress-driven mobility.

Drivers of Youth Migration from Rural India

a. Rural Employment Deficit

- Limited non-farm jobs; 49% migrants work as daily wagers and 39% in temporary industrial roles.

- Low returns from agriculture due to fragmented landholdings and climate exposure.

b. Education–Employment Mismatch

- Rural education lacks industry-relevant skills.

- Graduate unemployment exceeds 15% (CMIE 2024), indicating inadequate employability.

c. Income and Infrastructure Gaps

- Rural incomes fail to meet basic needs.

- Weak connectivity, inadequate credit access, and poor logistics hinder local enterprise formation.

d. Urban Pull Factors

- Cities offer perceived opportunities, higher wages, and mobility.

- However, migrants face unsafe housing, exploitation, and precarious informal jobs—88% lack social security.

Impact of Migration on Rural and Urban Landscapes

a. Urban Challenges

- Overcrowding, pollution, rising pressure on housing and infrastructure.

- Growth of slums in megacities like Delhi and Mumbai.

b. Rural Depopulation

- Loss of youth weakens agricultural productivity and local governance.

- Declining rural social capital affects community cohesion.

c. Social and Psychological Effects

- Family separation leads to stress, anxiety, and economic insecurity among dependents.

- Women migrants rarely enter the workforce, deepening gender gaps.

Policy Interventions and Initiatives

- MGNREGA ensures wage support during lean seasons, reducing distress migration.

- DDU-GKY, PMKVY provide vocational training to improve employability.

- PM-Mudra, Start-Up India, SVEP encourage rural entrepreneurship.

- 10,000 FPO initiative strengthens farmer collectives and value chains.

- BharatNet, PMGSY, rural BPOs expand digital and physical connectivity.

Way Forward: Reimagining Rural Education and Ecosystems

a. Integrating Education with Local Economies

- Embed vocational, digital, and agri-tech skills into rural curricula.

- Link schools and colleges to local enterprises and industries.

b. Diversifying Rural Non-Farm Sectors

- Develop employment in handicrafts, food processing, logistics, renewable energy, and agri-tourism.

c. Building Digital Ecosystems

- Invest in 5G connectivity, e-commerce platforms, tele-work hubs, and digital service centres.

d. Encouraging Local Entrepreneurship

- Promote success stories like Raigad’s BalaramBandagale to inspire reverse migration and rural innovation.

e. Strengthening Social Protection

- Ensure universal portability of PDS, health insurance, and pensions for mobile workers.

Conclusion

India must shift from a model where migration is a compulsion to one where it becomes a choice. Strengthening rural education, diversifying local economies, and empowering youth with market-ready skills can address structural causes of migration. A balanced rural–urban development framework—anchored in employment-linked learning, digital connectivity, and entrepreneurship—will help revitalise rural India and support inclusive, sustainable growth.

Comprehensive Modular Survey: Education 2025

- 01 Sep 2025

In News:

The Comprehensive Modular Survey: Education (CMS:E), 2025, conducted under the 80th round of the National Sample Survey (NSS), provides valuable insights into household expenditure, enrolment trends, and private coaching patterns in school education.

Covering 52,085 households and 57,742 students, this survey, conducted through Computer-Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI), offers nationally representative data at a critical juncture when India’s education sector is undergoing reforms under NEP 2020 and rapid digital transformation.

Key Findings of CMS: Education 2025

1. Enrolment Patterns

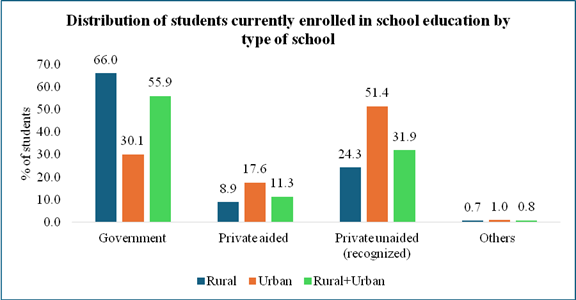

- Government schools dominate enrolment at 55.9%, with higher presence in rural areas (66%) compared to urban (30.1%).

- Private unaided schools account for 31.9% of enrolment, with stronger urban dominance.

2. Education Expenditure

- Average household spending per student:

- Government schools – ?2,863

- Non-government schools – ?25,002

- Overall, expenditure is significantly higher in urban areas (?23,470) than in rural areas (?8,382).

- Course fees constitute the largest expense (?7,111), followed by textbooks and stationery (?2,002).

3. Private Coaching

- Nearly 27% of students availed coaching, higher in urban areas (30.7%) than rural (25.5%).

- Expenditure gap: ?3,988 per student annually in urban areas vs ?1,793 in rural areas.

- At the higher secondary level, coaching costs rise to ?9,950 in urban areas compared to ?4,548 in rural areas.

4. Sources of Education Finance

- 95% of educational expenses were funded by household members.

- Only 1.2% students cited government scholarships as their primary funding source, highlighting weak institutional financial support.

Structural Developments in India’s Education Sector

- Digital and STEM Education: Initiatives like PM e-Vidya and Atal Tinkering Labs (8,000+ labs) promote digital and innovation-driven learning. India’s edtech sector attracted USD 3.94 billion (FY22), projected to grow further.

- Vocational and Skill Integration: NEP 2020 emphasizes skilling; the Union Budget 2025–26 allocated ?500 crore for AI Centres of Excellence in education.

- Rising Private Investment: With 100% FDI permitted, the Indian education market is projected to reach USD 125.8 billion by 2032.

- Higher Education Expansion: India now has 1,362 universities and 52,538 colleges, with Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) rising to 28.4% (FY25).

- Multilingual & Inclusive Education: Under NEP 2020, focus on regional languages and digital content aims to bridge disparities.

Challenges in Indian Education

- Infrastructure Gaps – Only 47% schools have drinking water; 53% have separate girls’ toilets (2023 data).

- Teacher Shortage – Over 4,500 secondary teachers lack proper training; sanctioned positions declined by 6% (2021–24).

- Low Public Spending – India spends 3–4% of GDP on education, below NEP’s target of 6%.

- Socio-Economic Disparities – Tribal and disadvantaged children face linguistic and access barriers.

- Learning Outcomes – 75% of Class 3 students cannot read Grade 2 text, highlighting rote learning dependence.

- Digital Divide – Only 18.47% of rural schools have internet, compared to 47.29% in urban areas.

- Gender Barriers – 33% of girls drop out due to domestic responsibilities (UNICEF).

Way Forward

- Enhanced Investment in infrastructure, teacher training, and digital access.

- Targeted scholarships and financial aid to reduce household burden.

- Curriculum reforms to shift from rote learning to competency-based assessments (e.g., PARAKH).

- Inclusive education policies for tribal, rural, and girl students.

- Public-Private Partnerships to leverage innovation, funding, and technology.

Conclusion

The CMS: Education 2025 survey underscores the centrality of government schools, the rising cost burden on families, and the growing role of private coaching in shaping education outcomes. While India is witnessing rapid expansion, digitalization, and global investment, challenges of equity, quality, and access persist. Addressing these gaps through sustained policy focus, enhanced funding, and inclusive reforms is essential for realizing the NEP 2020 vision and achieving SDG 4: Quality Education.

UGC Draft Curriculum Highlights Ancient Wisdom in Higher Education

- 30 Aug 2025

Background

The University Grants Commission (UGC) has released a draft Learning Outcomes-based Curriculum Framework (LOCF) for undergraduate programmes in fields such as anthropology, chemistry, commerce, economics, geography, mathematics, political science, home science, and physical education.

A defining feature of this framework is the inclusion of Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), aiming to blend traditional philosophies and practices with contemporary pedagogy. The draft has been made public for feedback from stakeholders.

Integration of Indian Knowledge Systems

The framework seeks to position higher education within India’s cultural and intellectual heritage, reflecting the vision of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, which emphasiseddecolonisation of curricula and recognition of indigenous wisdom.

Every subject has been asked to incorporate aspects of Indian traditions, linking them to modern learning outcomes.

Subject-Wise Highlights

- Mathematics

- Modules on mandala geometry, yantras, rangoli, kolam as algorithmic art forms.

- Study of temple architecture through ?y?di ratios.

- Contributions of Indian mathematicians in arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and calculus, and their influence on global traditions.

- Commerce

- Incorporation of Bhartiya philosophy and Gurukul pedagogy, focusing on holistic learning.

- Study of Kautilya’sArthashastra for insights into trade and financial systems.

- Ideas like Ram Rajya, Shubh-labh (profit with responsibility), CSR, and ESG frameworks integrated into modern governance discussions.

- Economics

- Emphasis on dharmic perspectives on wealth and prosperity.

- Exploration of indigenous exchange systems, agrarian values, dana (charity), and state-led economic roles.

- Ethical trade and collective enterprise highlighted as core themes.

- Chemistry

- Introduction of traditional Indian fermented drinks (kanji, mahua, toddy) in modules on alcoholic beverages.

- Integration of parmanu (ancient atomic concept) with modern atomic theory.

- Anthropology

- Curriculum draws on Charaka, Sushruta, Buddha, and Mahavira, focusing on their insights into the relationship between culture and nature.

Criticism and Concerns

- While NEP 2020 promotes interdisciplinarity, the LOCF allocates a large portion of credits to single-major courses. For example, chemistry students must take 96 out of 172 credits in core courses, reducing scope for cross-disciplinary learning.

- Critics, including some opposition-led states, allege that the draft encourages “saffronisation” of education.

- The key challenge lies in ensuring that cultural heritage is respected while preserving academic rigour, scientific temper, and global competitiveness.

Significance

The draft framework represents a paradigm shift in Indian higher education, with potential to:

- Decolonise curricula by embedding indigenous systems.

- Offer culturally rooted yet globally relevant education.

- Encourage ethical, sustainable practices across professional fields.

- Highlight India’s contributions to mathematics, medicine, governance, and economics.

Way Forward

The draft is currently open for feedback and may be revised before implementation. If adopted, it could reshape the intellectual foundation of higher education, grounding it more deeply in India’s heritage while aligning with international standards.

The real challenge, however, will be to ensure that ancient wisdom complements — rather than replaces — critical thinking, scientific inquiry, and multidisciplinary exploration.

Five Years of the National Education Policy 2020

- 05 Aug 2025

In News:

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, India’s third education policy since Independence, was envisioned as a transformative roadmap to make India a “global knowledge superpower.” Five years since its launch, the policy has driven important reforms in both school and higher education. However, progress has been uneven—while curriculum redesign, early childhood education, and digital learning have taken shape, federal tensions, institutional inertia, and funding constraints continue to slow its full realization.

Key Gains in School Education

The NEP replaced the 10+2 structure with a 5+3+3+4 model (foundational, preparatory, middle, secondary). The National Curriculum Framework (2023) set competency-based outcomes, and NCERT released new textbooks for classes 1–8, integrating subjects such as history and geography into a single volume.

Early childhood care and education (ECCE) has gained traction through the JaaduiPitara kits and a national ECCE curriculum. Delhi, Karnataka, and Kerala have enforced the minimum age of six for class 1. However, improving Anganwadi training and infrastructure remains critical.

Under NIPUN Bharat (2021), literacy and numeracy by class 3 became a national focus. Yet, survey data show proficiency levels at 64% (language) and 60% (math)—progressive but below NEP’s universal goals.

Higher Education Reforms

One of NEP’s boldest ideas, the Academic Bank of Credits (ABC) and National Credit Framework (NCrF), introduced flexibility with multiple entry-exit options: a certificate after one year, a diploma after two, and a four-year degree. While nearly 90% of HEIs report multidisciplinary curricula, only 36% have implemented multiple entry-exit, and just 64% maintain ABC records, indicating patchy adoption.

The Common University Entrance Test (CUET), introduced in 2022, streamlined admissions by replacing multiple entrance exams. Global outreach expanded, with IIT Madras (Zanzibar), IIT Delhi (Abu Dhabi), and IIM Ahmedabad (Dubai) opening campuses abroad, while foreign universities such as the University of Southampton entered India.

Digital education emerged as a strong adoption area: 96% of HEIs use SWAYAM/DIKSHA, and 94% invested in digital infrastructure. Yet, equitable access and integration of MOOCs into degree programs remain challenges.

Reforms in Progress

- Board exams: From 2026, CBSE will allow class 10 students to appear twice a year to reduce stress.

- Holistic assessment: PARAKH has developed competency-based report cards, though most boards are yet to implement them.

- Four-year undergraduate degrees: Adopted by some central universities and Kerala, but slowed by faculty shortages and weak infrastructure.

- Mother tongue instruction: Encouraged till class 5, with NCERT preparing multilingual textbooks.

Sticking Points and Bottlenecks

Some reforms remain stalled:

- Three-language formula has been rejected by Tamil Nadu as linguistic imposition.

- Teacher education reform lags, with the National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education still pending.

- Higher Education Commission of India (HECI), meant to replace UGC, remains in draft stage.

- Breakfast alongside midday meals, recommended by NEP, was rejected due to financial constraints.

Federalism poses a key hurdle. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal refused to adopt PM-SHRI schools, citing central overreach, leading to funding freezes under Samagra Shiksha. Karnataka oscillated—adopting and later scrapping the four-year UG model—while pursuing its own state education policy.

Conclusion

Five years on, NEP 2020 has delivered structural reforms in school curricula, foundational learning, higher education flexibility, and digital adoption. Yet, its transformative potential remains unrealized due to limited faculty capacity, uneven state cooperation, and financial bottlenecks. For NEP to succeed, the Union and states must collaborate, ensuring adequate funding, teacher training, and institutional autonomy. Without resolving these foundational issues, the NEP risks remaining a vision more on paper than in classrooms.

Foreign Universities in India: A New Era in Higher Education

- 30 Jun 2025

Context:

India is witnessing a transformative moment in its higher education sector with globally reputed foreign universities preparing to set up campuses within the country. Enabled by the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023, and inspired by the vision of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, this move could reshape the academic landscape. Locations such as GIFT City (Gujarat) and Navi Mumbai have been identified as early sites for these institutions. As of mid-2025, seven universities from the UK, five from Australia, and one each from the US, Canada, and Italy have initiated or secured regulatory approvals.

Drivers of Foreign University Interest in India

- Demographic and Economic Potential:India hosts over 40 million students in higher education, with a Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) below 30% (AISHE 2021–22), indicating untapped potential. A growing urban middle class, rising aspirations, and the need for globally competitive education have made India an attractive destination.

- Global Decline in Student Numbers:Countries in the Global North face declining domestic enrolments due to falling birth rates. In 2023, international students accounted for 22% in the UK, 24% in Australia, and 30% in Canada. Top U.S. universities reported up to 27% international enrolments, underscoring their reliance on overseas students for revenue.

- Policy Tightening in Host Nations:Visa caps and policy restrictions in Australia, the UK, and Canada have constrained student inflows. Consequently, foreign institutions are exploring in-country campuses in emerging markets like India to maintain their global reach and financial sustainability.

Opportunities and Advantages

- Academic Diversification: Indian students will gain access to internationally benchmarked curricula, faculty, and research ecosystems without the need to go abroad.

- Cost-Effective Alternative: For students unable to afford international education, foreign campuses in India provide a more affordable and accessible option.

- Quality Enhancement: The presence of foreign institutions could push Indian universities to raise academic standards through competition and collaboration.

- Regional Education Hub: India may also attract students from South Asia and Africa, enhancing its regional soft power.

Challenges Ahead

- Affordability: Tuition fees at foreign university campuses may still be beyond the reach of average Indian households, potentially limiting their impact to elite segments unless subsidized.

- Mixed Global Precedents: Similar ventures in China and Southeast Asia have seen varied success, with some facing regulatory and financial hurdles.

- Regulatory and Cultural Complexities: India’s bureaucratic processes, socio-cultural diversity, and policy uncertainties could pose operational challenges.

- Modest Initial Scale: In the short term, student intake and institutional presence are expected to be limited, with success depending on market response and adaptability.

Regulatory Framework and Future Outlook

The UGC’s FHEI Regulations, 2023, provide foreign institutions with autonomy in curriculum design, faculty recruitment, admissions, and repatriation of surplus funds. Only top 500 globally ranked universities, or those with exceptional expertise in niche domains, are eligible. These reforms reflect India’s commitment to making higher education globally competitive.

If effectively implemented, foreign campuses can act as catalysts for academic reform, foster global partnerships, and elevate India’s position as an education hub. However, ensuring affordability, equitable access, and academic integrity will be key to long-term success.

Nutrition and Education: UNESCO’s Call for Integrated Human Capital Development

- 02 Apr 2025

Context:

In March 2025, UNESCO released its global report titled “Education and Nutrition: Learn to Eat Well” at the ‘Nutrition for Growth’ summit in France. The report brings to light the critical intersection between child nutrition and educational outcomes, positioning school feeding programs not merely as welfare schemes but as foundational investments in human capital.

Global and Indian Context

As per the report, 418 million children across 161 countries benefit from school meal programs, yet over half of these initiatives lack adequate portions of fruits and vegetables. Alarmingly, nearly one-third of the programs include sugary beverages. This dietary imbalance is reflected in the rising tide of childhood obesity, which has doubled in over 100 countries in the past two decades.

In India, the PM-POSHAN (formerly Mid-Day Meal) scheme remains a vital intervention, feeding approximately 118 million children daily, making it one of the largest school meal programs globally. Despite this extensive reach, the report notes a persisting issue of "hidden hunger" — widespread micronutrient deficiencies stemming from poor dietary diversity.

Nutrition-Education Nexus

The report strongly advocates for recognizing nutrition as an enabler of learning. Well-balanced meals in schools contribute to better attention spans, memory retention, and academic performance. In countries like Brazil and Finland, where nutrition programs are closely aligned with educational frameworks, data shows improved enrolment, retention, and performance metrics.

School meals also serve as instruments of social equity, especially for children from low-income families and marginalized communities. They act as a safety net, improving attendance — particularly for girls — and reducing hunger-related learning barriers. When sourced locally, these programs can additionally boost rural economies and support sustainable agriculture, creating farm-to-table ecosystems.

Challenges Identified

The report flags several systemic challenges. A majority of school feeding programs are heavily dependent on staple grains, offering minimal variety. Many meals still include ultra-processed and low-nutrient foods, while nutrition education remains largely absent from school curricula — only 17 countries integrate it with national food standards.

Further, an urban-rural divide in infrastructure, such as cold storage and supply chains, leads to inconsistent delivery. Monitoring gaps also persist — just 8% of countries track school meals against WHO nutritional standards, making outcome assessment difficult.

Recommendations and Way Forward

UNESCO proposes a holistic approach for countries to bridge the education-nutrition divide:

- Curriculum Integration: Nutrition should be embedded into educational content across disciplines and levels.

- Science-Based Standards: National guidelines should align with WHO dietary recommendations.

- Local Procurement: Meal sourcing must prioritize seasonal and region-specific produce to enhance diversity.

- Teacher Training: Educators should be equipped to impart food literacy effectively.

- Robust Monitoring: Countries must develop national strategies on school nutrition with clear benchmarks, accountability, and evaluation mechanisms.

Conclusion

The report makes a compelling case that education and nutrition must be interlinked to foster meaningful development. Investing in nutritious school meals is not merely about feeding children — it is about shaping a healthier, more capable future generation. In the long run, a well-nourished child is better positioned to learn, thrive, and contribute to nation-building, making this a strategic priority for policymakers worldwide.

Revitalizing State Universities: NITI Aayog’s Vision for Quality Higher Education

- 11 May 2025

In News:

India’s higher education sector, the third largest in the world, is largely shaped by its state universities. In its recent report titled ‘Expanding Quality Higher Education through States and State Universities’, NITI Aayog critically analyses the systemic challenges in these institutions and offers a strategic roadmap to enhance their quality, inclusivity, and global competitiveness.

Role of State Universities in India’s Higher Education Ecosystem

State universities constitute nearly 80% of all higher education institutions in India and cater to the majority of enrolled students. They play a pivotal role in ensuring access to education across socio-economic and geographical divides, particularly in underserved regions. Their contribution is crucial to India’s goals of inclusive development, knowledge-driven growth, and human capital formation. Consequently, their performance directly influences India’s research output, innovation capacity, and global academic standing.

Challenges Highlighted in the Report

1. Inadequate Investment and Uneven Funding Patterns: The report underscores the lack of consistent public investment in higher education. While some states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu invest substantially, others like Karnataka, despite high college density and enrolment, spend comparatively less. This disparity leads to uneven development and limits potential in several regions.

2. Declining Financial Commitment from States: There is a noticeable decline in state-level financial support for higher education, compounded by limited capacity to implement recommended reforms. The report calls for greater central assistance to bridge fiscal gaps and ensure a uniform quality of education nationwide.

3. Quality Deficit and Research Gaps: State universities often lack robust infrastructure, qualified faculty, and research funding. As a result, India’s institutions fall short in global rankings, reflecting systemic weaknesses. There exists a pressing need to strengthen research ecosystems and align academic output with innovation.

4. Governance and Autonomy Issues: Excessive political interference and bureaucratic hurdles dilute institutional autonomy. The report flags the tension between central regulatory bodies and state institutions, urging reforms that empower universities with greater academic and administrative freedom.

Key Recommendations

- Strengthening Research and Innovation: The creation of Centres of Excellence, dedicated research universities, and collaboration with global institutions are essential. Funding mechanisms should prioritise research aligned with national goals.

- Pedagogical Reforms and Multidisciplinary Learning: Promotion of interdisciplinary education, digital tools, and experiential learning is advocated. Regular faculty training and industry collaboration are needed to ensure skill-oriented learning.

- Financial Reforms and Public-Private Partnerships: States should aim to increase GDP spending on higher education. The report recommends performance-linked funding and encourages PPP models for infrastructure and capacity building.

- Performance Monitoring: Over 120 performance indicators have been proposed to evaluate outcomes. A system of short-, medium-, and long-term targets will guide progress through regular institutional reviews.

- Governance Reforms: Autonomy is key to excellence. Decentralised decision-making, transparent accreditation, and robust ranking systems are essential for institutional accountability and quality assurance.

Implementation Challenges

The success of these reforms hinges on overcoming several hurdles. Financial constraints, political interference, and faculty shortages persist. Mobilising alternative funding sources like CSR, insulating academia from politics, and capacity building are crucial steps.

Conclusion

NITI Aayog’s blueprint provides a timely and necessary intervention to revitalise India’s state universities. These institutions, forming the bedrock of India’s higher education framework, must be empowered through coordinated action by both state and central governments. Only then can India realize its vision of inclusive, equitable, and globally competitive higher education.

India’s Human Development Index 2025

- 08 May 2025

In News:

India has made steady progress in the Human Development Index (HDI), improving its rank from 133rd in 2022 to 130th in 2023 among 193 countries. Its HDI value rose from 0.676 to 0.685, reflecting advancements in key areas such as health, education, and income. Despite these gains, significant challenges, particularly inequality, continue to limit India’s overall human development.

Understanding India’s HDI Progress

The HDI is a composite measure that captures a country’s average achievements in three core dimensions: health (life expectancy), education (years of schooling), and income (gross national income per capita). India currently belongs to the ‘medium human development’ category and is approaching the threshold for ‘high human development’ (an HDI value of 0.700).

Several factors have driven India’s recent improvement:

- Health: Life expectancy increased markedly from 58.6 years in 1990 to 72 years in 2023. This improvement is supported by flagship health schemes like Ayushman Bharat, the National Rural Health Mission, Janani Suraksha Yojana, and PoshanAbhiyaan, which have enhanced healthcare access and nutrition.

- Education: The expected years of schooling grew from 8.2 years in 1990 to 13 years in 2023, while mean years of schooling rose from 4.1 to 6.9 years. Policies such as the Right to Education Act and the National Education Policy 2020 have played critical roles in improving educational quality and accessibility.

- Income: India’s per capita Gross National Income surged from $2,167 in 1990 to $9,046 in 2023. Social welfare programs like MGNREGA and Jan Dhan Yojana have contributed to this growth by lifting approximately 135 million people out of multidimensional poverty between 2015-16 and 2019-21.

Persistent Challenges: Inequality and Gender Disparity

Inequality poses a major impediment to India’s HDI progress. It is estimated that disparities reduce India’s HDI by 30.7%, one of the highest losses in South Asia. The wealthiest 10% earn nearly 57% of the national income, while the poorest 50% share only 13%. Gender inequality further complicates the picture: India’s Gender Development Index (GDI) stands at 0.874, with female HDI (0.631) significantly lower than male HDI (0.722). Despite policy efforts, female labor force participation and political representation remain limited.

Regional and Global Context

Regionally, India lags behind neighbors like China (75th) and Sri Lanka (89th) but shares a similar HDI value with Bangladesh (130th), and surpasses Nepal (145th) and Pakistan (168th). Globally, the 2025 Human Development Report highlights a slowdown in HDI growth—the slowest since 1990—but emphasizes the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in fostering inclusive development. India holds 20% of global AI researchers, positioning it to harness AI’s potential in sectors such as healthcare, education, and productivity.

Strategic Innovations and National Initiatives

India’s pursuit of sustainable development complements its HDI goals through key initiatives:

- Scientists have developed a metal-free catalyst leveraging mechanical energy for sustainable hydrogen fuel production, supporting the National Green Hydrogen Mission to promote clean energy.

- The Indian Navy’s deployment of INS Sharda to the Maldives for its inaugural Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) exercise under the MAHASAGAR vision showcases India’s leadership in regional disaster preparedness and maritime security.

- Developments in regional defense, such as Iran’s unveiling of the solid-fuel GhassemBasir medium-range missile, highlight ongoing security challenges necessitating vigilance and capability enhancement.

Way Forward

To advance into the ‘high human development’ category, India must:

- Implement targeted policies to reduce income and gender inequalities.

- Invest in quality education and healthcare, especially for underserved populations.

- Promote inclusive economic growth benefiting marginalized groups.

- Leverage emerging technologies like AI responsibly to enhance public services without deepening disparities.

- Strengthen regional cooperation and disaster resilience to protect socio-economic gains.

Conclusion

India’s HDI improvement reflects meaningful progress in health, education, and income. Yet, to fully realize its human development potential, India must tackle persistent inequalities and strategically harness technological innovations alongside regional cooperation. With sustained, inclusive efforts, India can continue its upward trajectory toward equitable growth and global leadership.

Public Health Education in India

- 18 Mar 2025

In News:

India’s public health education sector stands at a critical juncture. Despite rapid academic expansion—with over 100 institutions now offering Master of Public Health (MPH) and related programs—the sector faces mounting challenges related to employment, quality, and funding. While international aid has declined, domestic investment remains limited, exacerbating systemic issues in workforce development.

Public Health: Constitutional and Strategic Significance

Article 47 of the Indian Constitution mandates the State to improve public health. A well-trained public health workforce is essential to achieve health equity, manage non-communicable diseases, address pandemics like COVID-19, and ensure effective delivery of health services at all levels.

Evolution and Growth of Public Health Education

Public health education in India has roots in colonial institutions, notably the All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, Kolkata (1932). Post-independence, community medicine was integrated into medical curricula. However, it was the launch of the National Rural Health Mission (2005) that marked a turning point, creating space for non-medical professionals in public health. Since then, MPH programs have proliferated—from just one institution in 2000 to over 100 today.

Government Initiatives

Key government efforts to strengthen public health education and training include:

- National Health Mission (NHM): Enhances public health systems and skill development.

- PM Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (PMSSY): Expands infrastructure and education through AIIMS-like institutions.

- Fellowship in Public Health Management (FPHM): Builds leadership capacities.

- National Programme for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NP-NCD) and Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP): Promote epidemiology and disease control training.

Persistent Challenges

- Employment Mismatch: A surge in MPH graduates has not been matched by job creation. Entry-level roles receive thousands of applications, and dedicated public health cadres in states remain underdeveloped.

- Lack of Regulation and Standardization: No central regulatory body ensures consistent curricula or quality standards. MPH programs are not under the purview of the NMC or UGC.

- Faculty Shortages and Weak Practical Training: Institutions often lack experienced faculty and real-world training integration, leaving graduates underprepared.

- Uneven Institutional Spread: States like Assam, Bihar, and Jharkhand have few or no public health colleges, deepening regional disparities.

- Funding Deficits: India's public health education receives minimal investment. For instance, the Data Protection Board was allocated just ?2 crore—reflecting systemic underfunding. International aid cuts, such as those from USAID, further strain the sector.

- Low Private Sector Absorption: Private hospitals prefer management professionals over MPH graduates. Development sector roles, heavily reliant on foreign grants, offer limited stability.

Way Forward

- Establish Public Health Cadres: States must create dedicated employment frameworks at all administrative levels.

- Regulate Education Quality: A Public Health Education Council under UGC/NMC should standardize curricula, faculty norms, and institutional benchmarks.

- Expand Institutional Capacity: Encourage public-private partnerships to open MPH colleges in underserved regions.

- Promote Experiential Learning: Mandate field training through internships in NHM, IDSP, and WHO-linked programs.

- Encourage Private Sector Hiring: Offer incentives for hiring MPH graduates in corporate and hospital settings.

- Increase Domestic Investment: Boost government funding for public health education and research, reducing reliance on foreign donors.

Conclusion

India’s public health education must transition from fragmented expansion to structured, quality-driven growth. Strengthening regulation, employment pathways, and training infrastructure is crucial for building a resilient health system and fulfilling the constitutional promise of health for all.

ASER 2024

- 30 Jan 2025

In News:

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024, released by the NGO Pratham, provides an insightful assessment of schooling and foundational learning levels across rural India.

Conducted in 17,997 villages across 605 districts, the survey reached over 6.49 lakh children aged 3–16 and tested more than 5 lakh for reading and arithmetic.

About ASER:

- Type: Household-based, citizen-led survey

- Initiated: 2005 (Annual till 2014; biennial since 2016)

- Scope:

- Tracks school enrollment (ages 3–16)

- Assesses basic reading and arithmetic skills (ages 5–16)

- Includes children in and out of school, across government, private, and informal institutions

- 2024: Introduced digital literacy assessment for ages 14–16

Key Findings of ASER 2024:

1. Enrollment Trends

- Pre-primary (Ages 3–5):

- Overall enrollment improved significantly.

- 3-year-old enrollment rose from 68.1% in 2018 to 77.4% in 2024.

- Anganwadis remain primary providers for 3–4-year-olds, while private preschools dominate among 5-year-olds.

- Elementary (Ages 6–14):

- Overall enrollment slightly declined from 98.4% (2022) to 98.1% (2024).

- Government school enrollment fell from 72.9% (2022) to 66.8% (2024).

- Private school enrollment, steadily rising since 2006, is regaining ground post-pandemic.

- Adolescents (Ages 15–16):

- Dropout rates fell from 13.1% in 2018 to 7.9% in 2024.

- However, female dropout (8.1%) remains higher than male.

2. Learning Outcomes

- Reading Skills:

- Std III: 23.4% in government schools could read Std II-level text (up from 16.3% in 2022).

- Std V: 44.8% could read Class II text, nearly matching 2018 levels (44.2%).

- Private schools yet to recover fully to pre-pandemic levels (59.3% in 2024 vs. 65.1% in 2018).

- Arithmetic Skills:

- Std III: 33.7% could perform basic subtraction (up from 25.9% in 2022, exceeding 28.2% in 2018).

- Std VIII: 45.8% could solve basic problems, showing consistent improvement.

Trend: Arithmetic recovery has outpaced reading, with government schools showing faster gains than private ones.

3. Digital Literacy (Ages 14–16)

- Access: Nearly 90% have access to smartphones.

- Ownership:

- 36.2% of boys own smartphones vs. 26.9% of girls.

- Usage:

- 82.2% use smartphones; only 57% for education, but 76% for social media.

- Safety Awareness:

- 62% know how to block/report users, and 55.2% can make profiles private.

4. School Infrastructure & Observations

- Attendance:

- Student attendance improved from 72.4% (2018) to 75.9% (2024).

- Teacher attendance rose from 85.1% to 87.5% in the same period.

- Facilities:

- Usable girls' toilets increased from 66.4% to 72%.

- Drinking water availability rose from 74.8% to 77.7%.

- Playground access remains stable (~66%).

- Learning Resources:

- Use of non-textbook reading materials (e.g., stories, folk tales) rose from 36.9% to 51.3%.

- Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN):

- 80%+ of schools implemented FLN activities.

- 75% had at least one FLN-trained teacher.

Significance of Elementary Education:

- Foundational for Learning: Builds core skills vital for academic progression.

- Social Development: Encourages interaction, empathy, teamwork, and communication.

- Emotional and Cognitive Growth: Stimulates curiosity, motivation, and self-confidence.

- Economic Multiplier: Strong early education contributes to long-term national productivity and innovation.

Persistent Challenges:

- Infrastructure Deficits:

- Over 1.5 lakh schools lack functional electricity.

- 67,000 schools lack toilets; only 33.2% have usable disabled-friendly toilets.

- Technology Divide: Only 43.5% of government schools have computers vs. 70.9% in private schools.

- Human Resource Gaps: Around 1 lakh schools function with only one teacher.

- Social Barriers:

- Caste, class, rural-urban, and gender divides restrict equal educational access.

- Language barriers affect non-Hindi/English speakers due to lack of regional textbooks.

Key Government Initiatives:

- National Education Policy (NEP) 2020

- PM SHRI Schools

- Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan

- Mid-Day Meal Scheme

- Beti Bachao Beti Padhao

- National Programme on Technology Enhanced Learning (NPTEL)

- PRAGYATA (Guidelines for digital education

Way Forward:

- Early Interventions: Focus on retention among disadvantaged groups.

- Inclusive Learning Models: Introduce flexible/part-time programs for working children.

- Supplementary Literacy: Target out-of-school and dropout children with bridge courses.

- Local Governance: Establish District School Boards for planning and accountability.

- Infrastructure Expansion: Ensure school access within 1 km in underserved regions.

- Parental Awareness: Launch community campaigns on education's long-term benefits.

Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) Report

- 10 Jan 2025

In News:

The Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) report for 2023-24 reveals a significant decline in school enrolment across India, highlighting critical challenges in the education sector. The total enrolment in grades 1-12 fell by over 1.55 crore students, from 26.36 crore (2018-2022 average) to 24.8 crore in 2023-24. This represents a 6% drop, with the biggest declines occurring in government schools.

Key Findings:

- Enrolment Decline:

- In 2023-24, enrolment decreased from 25.17 crore in 2022-23 to 24.8 crore.

- The drop was not only in government schools (5.59%) but also in private schools (3.67%).

- States like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra saw the largest decreases.

- The decline in enrolment is despite an increase in the number of schools, from 14.66 lakh in 2022 to 14.72 lakh in 2023.

- Methodology Change:

- A significant change in the data collection methodology occurred in 2022-23, including linking enrolment to Aadhaar numbers, aimed at reducing data duplication.

- While this has improved data accuracy, it has also led to the removal of inflated figures, explaining part of the enrolment drop.

- Despite these changes, there has been a notable decline of 37 lakh students from 2022-23 to 2023-24, which remains unexplained in the report.

- Gender and Age Trends:

- Boys’ enrolment declined by 6.04%, and girls’ by 5.76%, reflecting a uniform drop across gender groups.

- The dropout rates increase as students progress through school, with the highest dropout at the secondary level.

- Infrastructure and Facilities:

- While most schools have basic facilities like electricity and gender-specific toilets, advanced infrastructure like functional computers (57%) and internet access (53%) is lacking in nearly half of schools.

- This technological gap exacerbates regional disparities and affects educational quality, particularly in rural areas.

- State-Specific Impact:

- Jammu and Kashmir, Assam, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh saw the highest reductions in the number of schools.

- Many school closures or mergers have led to increased distances for students, causing further dropouts during re-admission processes.

Socio-Economic Barriers:

- Economic hardships, migration, and inadequate facilities contribute to the enrolment decline.

- Low-income families and backward regions struggle to prioritize education, further affecting enrolment and retention.

Government Initiatives:

- Initiatives like the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, and Right to Education Act (RTE) have made strides in primary education but face challenges in secondary education.

- Education spending has hovered around 4-4.6% of GDP, which is insufficient to meet the needs of the education system.

Moving Forward:

- Targeted Interventions: Focus on expanding vocational training, incentivizing school attendance, and improving digital infrastructure in schools.

- Address Regional Disparities: Conduct audits to address school shortages in densely populated areas and consolidate underutilized urban schools.

- Enhancing Teacher Quality: Invest in teacher training and encourage innovative teaching methods.

- Community Engagement: Promote local participation in school management to address specific educational needs.

Conclusion:

The UDISE+ 2023-24 report underscores the need for urgent reforms in India's education system, focusing on increasing enrolment, reducing dropout rates, and ensuring equitable access to quality education. By addressing these challenges with targeted policies, India can move closer to achieving its educational goals.

Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) 2023-24 Report

- 04 Jan 2025

In News:

The UDISE+ report for 2023-24, released by the Ministry of Education, presents key insights into India’s school education system. UDISE+ serves as a comprehensive database, tracking student enrolment, school infrastructure, and other educational parameters, enabling efficient policy implementation and gap identification.

Key Findings:

- Decline in School Enrolment: Enrolment figures in Indian schools have witnessed a significant decline for the first time in recent years. The total enrolment dropped from 26.36 crore (2018-22 average) to 25.17 crore in 2022-23 and further to 24.8 crore in 2023-24, marking a fall of 1.55 crore students or nearly 6%. This drop is attributed to the improved data collection methods which helped eliminate duplicate entries, especially students enrolled in both government and private schools.

- Gender and School Type-wise Trends: The enrolment drop was observed across both government and private schools. Government schools saw a decline of 5.59%, whereas private schools experienced a 3.67% reduction. Gender-wise, the enrolment of boys decreased by 6.04%, while girls’ enrolment dropped by 5.76%, compared to the 2018-22 average.

- State-wise Data: The enrolment drop was not uniform across states. Bihar recorded the largest decline, with a loss of 35.65 lakh students, followed by Uttar Pradesh (28.26 lakh) and Maharashtra (18.55 lakh). In contrast, states like Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Jammu & Kashmir, and Telangana saw an increase in enrolment during the same period.

- Level-wise Trends: The most significant declines were recorded at the primary (Classes 1-5), upper primary (Classes 6-8), and secondary (Classes 9-10) levels. However, enrolment in pre-primary and higher secondary (Classes 11-12) levels showed an increase in 2023-24 compared to the previous average.

- Impact of Data Refinement: The implementation of Aadhaar-linked student data collection has enhanced the accuracy of enrolment figures. The de-duplication process helped remove cases of students being enrolled in both government and private schools. This revision is expected to provide more accurate data for targeted educational schemes and improve the effectiveness of government programs like Samagra Shiksha and PM POSHAN.

Challenges in Education

Despite the improvements in data collection, several systemic issues persist:

- Access and Retention: High dropout rates, especially at the secondary level, remain a challenge for sustained student retention.

- Disparities among Marginalized Groups: Enrolment among SC, ST, OBC, and minority communities showed a notable decline, reflecting existing inequities in the education system.

- Infrastructure and Teacher Training: Uneven distribution of resources and insufficient teacher training continue to hamper educational outcomes, affecting quality and student engagement.

Way Forward

To address these challenges, the following steps are critical:

- Strengthening NEP 2020: The National Education Policy aims for universal Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) by 2030, with a focus on skill-based learning and inclusive education.

- Teacher Capacity Building: There is a need for targeted interventions to improve teacher quality and address gaps in the student-teacher ratio.

- Infrastructure Optimization: Schools should optimize their resources based on enrolment trends to improve access and address disparities.

- Data-Driven Monitoring: Continuous monitoring using student-specific data will help identify dropouts and allocate resources efficiently.

Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004

- 09 Nov 2024

In News:

The Supreme Court recently upheld the constitutional validity of the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004 (also called the Madarsa Act), while striking down certain provisions related to the granting of higher education degrees. The Court overturned the Allahabad High Court's previous decision, which had deemed the Act unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the principle of secularism.

What is the Madarsa Act?

The Madarsa Act provides a legal framework for regulating madrasas (Islamic educational institutions) in Uttar Pradesh. The Act:

- Establishes the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education, which oversees the curriculum and examinations for madrasas.

- Ensures that madrasas follow the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) curriculum for mainstream secular education alongside religious instruction.

- Empowers the state government to create rules for regulating madrasa education.

Allahabad High Court's Ruling

In March 2024, the Allahabad High Court declared the Madarsa Act unconstitutional, citing:

- Violation of secularism: The Court argued that the Act's emphasis on compulsory Islamic education, with modern subjects being optional, discriminated on religious grounds, violating the secular nature of the Constitution.

- Right to Education: The Court also claimed that the Act denied quality education under Article 21A, which guarantees free and compulsory education to children.

- Higher Education Degrees: The Act's provisions allowing the granting of Fazil and Kamil degrees were found to conflict with the University Grants Commission Act, 1956, which regulates higher education.

Supreme Court's Ruling

The Supreme Court overturned the Allahabad High Court's decision on several grounds:

- Basic Structure Doctrine: The Court clarified that the basic structure doctrine, which applies to constitutional amendments, does not apply to ordinary legislation like the Madarsa Act. Therefore, a law cannot be struck down simply for violating secularism unless explicitly prohibited by the Constitution.

- State's Authority to Regulate Education: The Court held that the state has the right to regulate education in minority institutions, as long as the regulation is reasonable and rational. It emphasized that the Madarsa Act does not deprive these institutions of their minority character.

- Right to Education for Minority Institutions: Referring to a 2014 decision, the Court ruled that the Right to Education Act (RTE) does not apply to minority institutions, as it would undermine their right to impart religious education and self-administer.

Striking Down Higher Education Provisions

While upholding most of the Act, the Supreme Court struck down the provisions related to higher education degrees (Fazil and Kamil). It ruled that:

- Section 9 of the Act, which allowed the Board to grant these degrees, is in conflict with the University Grants Commission Act, which only permits degrees to be awarded by universities recognized by the UGC.

Implications of the Ruling

- Regulation of Madrasa Education: The ruling affirms the state's authority to ensure quality education in madrasas, balancing religious instruction with secular subjects.

- Protection of Minority Rights: By upholding the Madarsa Act, the Court protected the rights of religious minorities to run educational institutions while ensuring they meet educational standards.

- Focus on Inclusivity: The judgment emphasizes the integration of madrasas within the broader educational framework, ensuring that madrasa students receive quality education.

In conclusion, the Supreme Court's decision supports the regulation of madrasa education while safeguarding the rights of minority institutions, except in areas related to the granting of higher education degrees, which remain under the jurisdiction of the UGC Act.

The UGC has issued revised guidelines on Mulya Pravah 2.0 – Inculcation of Human Values and Professional Ethics in Higher Education institutions (The Hindu)

- 09 Jan 2024

Why is it in the News?

The University Grants Commission (UGC) has been issuing regulations, guidelines and directives at breakneck speed that some of the important ones miss drawing the attention of the higher education community.

Context:

- The University Grants Commission (UGC) has introduced Mulya Pravah 2.0 to enhance the ethical landscape of higher education institutions.

- This evolved guideline, succeeding its 2019 predecessor, aims to instil human values and professional ethics, actively combating unethical practices that have permeated various institutions.

- The primary focus involves constructing value-based institutions that resonate with fundamental duties and constitutional values, urging a commitment to integrity and ethical conduct.

What is Mulya Pravah?

- Officially notified in 2019, Mulya Pravah aims to instil human values and professional ethics within higher education institutions.

- Its explicit objective is to cultivate value-based institutions by guiding individuals and institutions toward fostering profound respect for fundamental duties, constitutional values, and a strong connection with the country.

What is Mulya Pravah 2.0?

- Mulya Pravah 2.0, a revised guideline by the University Grants Commission (UGC), is designed to foster ethical practices and human values within higher education institutions.

- Its inception was prompted by revelations from a survey among human resource managers, uncovering unethical practices like favouritism, sexual harassment, and gender discrimination in various organisational processes.

- The primary objective of this guideline is to construct value-based institutions by nurturing a sense of respect for fundamental duties, and constitutional values, and fostering a connection to the nation.

Key Features of Mulya Pravah 2.0:

- Addressing Unethical Practices: Mulya Pravah 2.0 confronts the prevalent unethical practices identified in higher education institutions, as uncovered by a survey involving human resource managers.

- These malpractices encompass favouritism, sexual harassment, gender discrimination, inconsistent discipline, lack of confidentiality, and unscrupulous dealings with vendors for personal gain.

- While acknowledging that such issues may extend beyond higher education, this guideline serves as a commendable initiative toward fostering ethical conduct.

- Emphasis on Transparency: A pivotal aspect of Mulya Pravah 2.0 is its advocacy for absolute transparency in administration. Decision-making within higher education institutions is expected to be guided solely by institutional and public interest, free from biases.

- The guideline stresses the elimination of discriminatory privileges and underscores the importance of penalizing corruption.

- It urges the establishment of a conducive culture and work environment, aligning actions with the best interests of the institution.

- Guidelines Emphasize Upholding Values: Mulya Pravah 2.0 mandates that higher education institutions uphold values such as integrity, trusteeship, harmony, accountability, inclusiveness, commitment, respectfulness, belongingness, sustainability, constitutional values, and global citizenship.

- This intervention is timely, considering the diminishing prevalence of these values. Officers in universities are entrusted with ensuring strict adherence to these values both in letter and spirit.

- Guidelines Remind Institutions to Act in the Best Interest: Mulya Pravah 2.0 serves as a reminder for stakeholders to act in the best interest of their institution, fostering a conducive culture and work environment for teaching, learning, and research while developing the potential of the institution.

- It explicitly states that officers and staff must refrain from misappropriating financial and other resources.

- Additionally, it calls for a refusal to accept gifts, favours, services, or other items from any entity that may compromise the impartial performance of duties.

What are the Challenges in the Effective Implementation of Mulya Pravah 2.0?

- Sincerity and Commitment of Higher Education Regulators: The mere issuance of guidelines may prove insufficient if higher education regulators lack sincere commitment to enforce the provisions of Mulya Pravah 2.0.

- The UGC must demonstrate unwavering determination, setting a precedent by exhibiting zero tolerance for any form of corruption or ethical violations within the academic sphere.

- Institutional Resistance to Change: Established norms and practices within higher education institutions may resist the infusion of Mulya Pravah 2.0's principles, as institutional cultures can be deeply ingrained.

- Overcoming institutional inertia requires proactive efforts by university administrators, faculty, and other stakeholders to embrace and implement the ethical guidelines.

- Lack of Monitoring Mechanisms: Effective implementation requires robust monitoring mechanisms to track and evaluate adherence to the guidelines at various levels.

- The absence of a comprehensive monitoring framework may lead to laxity, allowing unethical practices to persist unchecked.

- Resistance from Internal Stakeholders: Faculty, staff, and student unions might resist the guidelines, perceiving them as an imposition on their autonomy or a threat to established practices.

- Overcoming resistance necessitates effective communication, collaboration, and building consensus among all internal stakeholders.

- Balancing Transparency and Confidentiality: The guideline's emphasis on maintaining confidentiality might clash with the broader societal demand for transparency in higher education institutions.

- Striking a delicate balance between the two is crucial to avoid potential conflicts and ensure the right to information is not compromised.

- Undefined Parameters and Ambiguities: Some aspects of Mulya Pravah 2.0, such as what constitutes a dignified manner for raising issues, lack clear definitions.

- Ambiguities in the guideline could lead to misinterpretations, allowing room for manipulation and misuse.

- Legal and Regulatory Compliance: Ensuring that institutions adhere to the legal and regulatory framework while implementing Mulya Pravah 2.0 is essential.

- Non-compliance or overlooking legal aspects may render the guideline ineffective or subject to legal challenges.

- Cultural and Regional Variations: Higher education institutions exhibit diverse cultural and regional variations, influencing the reception and interpretation of ethical guidelines.

- Tailoring the implementation strategy to accommodate these variations is vital for the guidelines to resonate across different contexts.

- Inadequate Training and Awareness Programs: The success of Mulya Pravah 2.0 depends on the understanding and active participation of all stakeholders.

- Insufficient training and awareness programs may result in a lack of clarity regarding the guidelines, reducing their impact.

What Steps Can Be Taken to Improve Governance in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)?

- Addressing the Issue of Confidentiality: The guideline should advocate for institutions to promptly publish agendas, proceedings, and minutes of meetings held by their decision-making bodies, sub-committees, and standing committees.

- Furthermore, institutions are encouraged to make their annual reports and audited accounts accessible to the public.

- This proactive disclosure can act as a deterrent against malpractices and contribute significantly to rebuilding public trust in institutional operations.

- Addressing Teachers’ Associations: Recognizing the significant impact teachers have on students' character, personality, and careers, Mulya Pravah 2.0 emphasizes that teachers should serve as role models.

- This involves exhibiting good conduct and maintaining high standards of dress, speech, and behavior for students to emulate.

- While the guideline underscores the expectation for teachers to adhere to university rules and policies, it does not explicitly address the role or function of teachers' associations, which warrants attention for a comprehensive approach.

- Clarity on the Definition of 'Dignified Manner' for Unions and Support: Mulya Pravah 2.0 anticipates the support of staff and student unions in development activities while urging them to raise concerns in a dignified manner.

- However, the guideline lacks a clear definition or explanation of what constitutes a 'dignified manner.'

- This absence leaves room for potential misuse, allowing the provision to be wielded in ways that may threaten, silence, or undermine the collective voices of stakeholders.

- A clear definition is crucial to avoid such misinterpretations and promote a healthy collaborative environment.

Conclusion

Mulya Pravah 2.0, introduced by the University Grants Commission, represents a commendable stride in instilling ethical values within higher education. Nonetheless, addressing its challenges necessitates inclusive discussions with all stakeholders. Effective implementation is imperative for realizing its potential to enhance the quality and sustainability of decisions within the educational sphere.

Parliament Panel Findings on the New Education Policy, 2020 (The Hindu)

- 27 Sep 2023

Why is it in the News?

The Education Committee of the Parliament has just presented a report about how the National Education Policy (NEP) from 2020 is being put into action in higher education.

Assessment in the report:

- The report checks how well the National Education Policy (NEP) from 2020 is being used in higher education and what progress has been made.

- In India, there are currently 1043 universities.

- Most of them, around 70%, are run by state laws, while about 18% are managed by the Central Government.

- When it comes to students, 94% of them study at state or private institutions, and only 6% are in central institutions.

- The report says that more students are going to college now compared to a few years ago. This is measured using something called Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER), which has gone up from 24.1% in 2016-17 to 27.3% in 2020-21. It's also improved for ST and SC students during this time.

- GER is like a way to see how many students in the right age group (18-23 years) are in higher education compared to the total population.

Report's Status of Implementation:

- Things are going well with the implementation of NEP 2020, thanks to different initiatives like PM Schools for Rising India (PM SHRI), e-VIDHYA, and NIPUN Bharat. The goal is to change higher education to be more inclusive, flexible, and meet global standards.

- Jammu and Kashmir is leading the way by being one of the first places in India to start using NEP 2020 in all Higher Education Institutions starting from 2022.

- NEP 2020 wants students to become more creative and innovative. It encourages connections between colleges and industries and works on joint programs.

- Indian universities will get more freedom to set up campuses in other countries and welcome top 100 universities from around the world to work in India.

- NEP 2020 also allows students more flexibility with something called "Multi Entry and Multiple Exit (MEME)" options, which gives them more choices in their education.

Issues Related to NEP:

- Accessibility: Some students in economically disadvantaged areas can't easily access higher education because of money problems, where they live, and because they might feel like they don't belong due to stereotypes.

- Multiple Entry And Multiple Exit (MEME)System: Even though the MEME system seemed flexible, the report suggests it might not work as well in India as it does in Western countries.

- Language Barrier: Most higher education institutions use English to teach, but not many teach in local languages. This can be a problem for students who are more comfortable in their local language.

- Lack of Funding: India needs to spend more on education. Right now, it's only about 2.9% of the country's total income (GDP), but experts say it should be 6%. This means there's not enough funding for education.

Way Forward

- By 2030, the goal is to have at least one multi-purpose higher education institution in every district in India. And by 2035, they want 50% of students to be in higher education, including vocational training.

- They want to focus more on research and innovation to help India file more patents and improve its global ranking.

- To get more money for education, Higher Education Financing Agency (HEFA) should look for funds from sources other than the government, like private companies, foundations, and international banks.

- They plan to make better use of technology in education. Creating a National Educational Technology Forum (NETF) will help expand digital resources and make India a top place for knowledge.

- They also want to make it easier for students who study different subjects to get credit for their work. This will help them move between schools and colleges more smoothly.

National Education Policy (NEP) 2020:

- The National Education Policy, created in July 2020, shows what India's new education system will look like.

- A group led by Shri K. Kasturirangan made this policy.

- NEP 2020 has five important ideas: making education affordable, easy to access, high-quality, fair for everyone, and making sure everyone is responsible for learning.

- It's like a big plan to change both basic and higher education in India by 2040.

- This is the third big education plan since India became independent. The earlier ones were made in 1968 and 1986.

- The new policy focuses on things like studying different subjects, using technology, writing well, solving problems, thinking logically, and getting experience in different jobs.