Lokpal of India

- 31 Oct 2025

In News:

The Lokpal of India, established under the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013, was envisaged as an independent anti-corruption ombudsman capable of investigating complaints against high public officials, including the Prime Minister, Union Ministers, MPs and government officials.

Conceived in the backdrop of the 2011 anti-corruption movement, the institution began functioning meaningfully only in 2019, when the first Lokpal was constituted—marking a long-awaited step in strengthening mechanisms for integrity and transparency in governance.

Mandate and Powers

- The Lokpal is empowered to conduct inquiries and investigations under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988.

- Its jurisdiction extends to all public servants—Groups A to D—besides heads of government-funded institutions.

- It possesses quasi-judicial powers, including summoning witnesses, demanding documents, ordering asset freezes, and recommending prosecution.

- Crucially, it maintains supervisory authority over the CBI in cases referred by it, reinforcing independent and credible investigations.

- The Lokpal’s composition includes a Chairperson and up to eight members—half of them judicial. As of 2025, Justice A.M. Khanwilkar (retd.) serves as Chairperson, supported by a seven-member team. Members are appointed by the President upon the recommendation of a selection committee comprising the Prime Minister, Speaker of Lok Sabha, Leader of Opposition, Chief Justice of India, and an eminent jurist.

Performance Crisis and Data Trends

Despite its powerful mandate, the Lokpal’s performance has raised serious concerns. Since inception, it has received 6,955 complaints, yet only 289 preliminary inquiries have been ordered. Out of these, a mere seven cases have progressed to the prosecution stage—an alarming indicator of institutional underutilisation.

The declining public engagement is sharper still. Annual complaints peaked at 2,469 in 2022–23 but plummeted to 233 in 2025, suggesting fading public confidence. Nearly 90% of all complaints were received in its first four years (2019–2023), while the past three years recorded only 691 complaints combined.

Civil society groups have criticised the procedural rigidity of the Lokpal. Activists point out that many complaints are dismissed on technical grounds such as format errors, while substantive allegations remain unaddressed. Further, the Lokpal’s failure to upload annual reports since 2021–22 has generated questions about its transparency and accountability.

Institutional Weaknesses and Controversies

A major lacuna has been the delayed operationalisation of the prosecution wing, notified only in June 2025—twelve years after the enactment of the Lokpal Act—severely constraining its ability to pursue legal action. The credibility of the institution also came under public scrutiny when it issued a tender to procure seven BMW 330Li luxury cars for its Chairperson and members. Critics argue that an anti-corruption body must demonstrate fiscal restraint and ethical prudence in its own functioning.

Way Forward

Strengthening the Lokpal requires structural, procedural, and ethical reforms. A real-time digital dashboard should be created to enable public tracking of cases and reduce opacity. Complaint formats must be simplified to ensure accessibility for ordinary citizens. Institutional autonomy must be reinforced with adequate staffing for inquiry and prosecution wings. Annual reports should be mandatorily published and tabled in Parliament. Above all, Lokpal must cultivate public trust by adopting austerity and demonstrating moral credibility.

Conclusion

The Lokpal was created to be the custodian of public integrity—an independent safeguard against high-level corruption. However, its diminishing complaint inflow, administrative inertia, and controversies signal a crisis of legitimacy. Revitalising the institution through stronger transparency, greater accountability, and ethical restraint is essential if it is to fulfil its constitutional promise of clean and accountable governance.

Blockchain and the National Blockchain Framework (NBF)

- 30 Oct 2025

In News:

Blockchain technology, once associated primarily with cryptocurrencies, has emerged as a transformative tool for establishing digital trust, enhancing transparency, and reducing systemic inefficiencies in governance. India, aiming to modernise its public service delivery architecture, has adopted a strategic approach through the National Blockchain Framework (NBF), launched in September 2024 with a budget of ?64.76 crore.

Understanding Blockchain Technology and Its Governance Utility

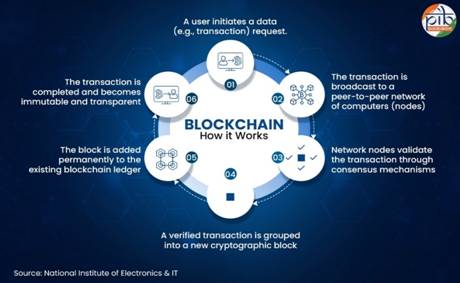

- Blockchain is a distributed, immutable and cryptographically secure ledger of transactions maintained across multiple nodes. Its inherent strengths—tamper resistance, decentralisation, and transparency—make it an ideal backbone for public data systems.

- India’s governance needs are best served by permissioned private blockchains, where authorised entities validate transactions while ensuring confidentiality. Other blockchain variants—public, consortium, and hybrid models—offer differing levels of access and decentralisation but are less suited for sensitive government datasets.

Core Architecture of the National Blockchain Framework

1. Vishvasya Blockchain Stack

At the heart of the NBF is the Vishvasya Blockchain Stack, an indigenous and modular platform offering:

- Blockchain-as-a-Service (BaaS) to enable rapid deployment of blockchain applications without the need for independent infrastructure.

- Distributed infrastructure across NIC data centres in Bhubaneswar, Pune, and Hyderabad for resilience and fault tolerance.

- Permissioned blockchain layer, ensuring participation only by verified entities.

- Open APIs and integration services that simplify connectivity with existing e-governance platforms.

2. NBFLite – Sandbox for Innovation

- NBFLite provides startups, researchers, and academic institutions with a controlled environment to prototype blockchain solutions using pre-configured smart contract templates for supply chains, certificates, and governance use cases.

3. Praamaanik – Mobile App Verification

- Praamaanik uses blockchain to verify the authenticity of mobile applications, protecting users from counterfeit apps and fraudulent customer support platforms.

4. National Blockchain Portal

- This serves as the unified gateway for guidelines, standards, and adoption roadmaps, promoting interoperability across sectors.

Blockchain-Enabled Chains Transforming Public Service Delivery

- Certificate and Document Chain: Government agencies use blockchain for secure issuance, storage, and verification of documents such as academic records, ration cards, driving licences, and birth/death certificates.Over 34 crore documents have been verified using this system.

- Logistics Chain: Used for tracking goods across supply stakeholders.Example: Karnataka’s Aushada system tracks medicines from manufacturers to hospitals, ensuring authenticity, preventing spurious drugs, and improving traceability.

- Property Chain: Immutable records of property transactions help reduce land disputes, establish ownership clarity, and expedite land transfers.

- Judiciary Chain and ICJS: Blockchain supports electronic delivery of summons, bail orders, and judicial notices.The Inter-operable Criminal Justice System (ICJS) integrates evidence, case files, and judicial documents across agencies for seamless coordination.

Sectoral Adoption by National Regulators

- TRAI employs Distributed Ledger Technology to monitor SMS transmission, reducing spam and enhancing regulatory compliance for over 1.13 lakh entities.

- RBI uses blockchain for its Digital Rupee (e?) pilot, demonstrating secure, traceable digital payments.

- NSDL has adopted blockchain for Debenture Covenant Monitoring, enabling time-stamped, tamper-proof monitoring of asset cover and compliance.

Capacity Building and Skill Development

MeitY has trained 21,000+ officials on blockchain applications. Academic initiatives—PG Diploma in FinTech & Blockchain, C-DAC’s BLEND programme, and FutureSkills PRIME—are developing specialised talent for India's blockchain workforce.

Way Forward

India is testing blockchain-based solutions for land records, GST chain, blood bank management, and PDS transparency. The NBF represents a strategic shift from fragmented digital systems to a unified trust-based digital governance model, positioning India as a global leader in blockchain-enabled public services.

UNESCO Global Education Report 2025

- 29 Oct 2025

In News:

The UNESCO Global Education Report 2025 offers a critical evaluation of global progress toward gender equality in education, exposing persistent disparities despite decades of international commitments. Although substantial improvements have been recorded since the 1995 Beijing Declaration, an alarming 133 million girls worldwide remain out of school, signalling unfinished global obligations.

Progress Achieved

- The report highlights significant gains in enrolment and access. Compared to 1995, 91 million more girls are in primary school and 136 million more are enrolled in secondary education.

- Tertiary education has witnessed the most dramatic progress, with women's enrolment tripling from 41 million to 139 million. These trends reflect global investments in universal education programmes, gender inclusion policies, and financial support mechanisms.

Regional Variations

Despite overall progress, regional disparities persist. Central and South Asia have achieved gender parity in secondary education, demonstrating effective policy interventions. Conversely, Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania continue to lag, constrained by poverty, rural isolation, armed conflicts, and socio-cultural restrictions. In countries such as Mali and Guinea, lower secondary completion rates for girls remain below 20%, indicating severe structural inequities. In contrast, Latin America and the Caribbean show higher dropout rates among boys, underscoring region-specific challenges.

Quality and Inclusivity Deficits

The report stresses that enrolment gains alone do not translate into gender equality. Only two-thirds of countries have compulsory sexuality education at the primary level, and gender biases persist in textbooks and curricula. These embedded stereotypes perpetuate discriminatory norms and restrict girls’ aspirations and subject choices. Safety concerns—including school-related gender-based violence—further hinder learning continuity, particularly for adolescent girls.

Leadership Inequality

Although women comprise a significant proportion of the global teaching workforce, their presence in leadership positions remains limited. Only 30% of higher education leadership roles are held by women, revealing systemic barriers such as limited institutional support, leadership pipelines, and entrenched patriarchal structures. This leadership gap undermines gender-sensitive decision-making within education systems.

Economic and Social Implications

UNESCO reinforces that girls’ education is not merely a human rights imperative but an economic and socio-developmental necessity. The World Bank (2024) estimates that closing the gender gap in education could boost global GDP by $15–30 trillion, reflecting the massive economic potential of women’s participation in the workforce. Educated girls contribute to improved health outcomes, reduced poverty, enhanced labour force participation, and greater intergenerational development.

Way Forward

The report calls for gender-transformative policies—including equitable curricula, strengthened pathways for women in leadership, expanded sexuality education, safer learning environments, and evidence-based monitoring. Achieving the vision of the Beijing Declaration requires political will, sustained investments, and community-level engagement to dismantle structural barriers.

Can Rural Education Transform Migration Patterns? Reimagining Opportunities Beyond Cities

- 28 Oct 2025

In News:

Migration has been a central feature of India’s socio-economic evolution, but the growing exodus of rural youth to urban centres signals deep developmental imbalances. While migration is natural in a dynamic economy, its scale—particularly among young people—highlights failures in generating dignified rural livelihoods, aligning education with market needs, and creating resilient local ecosystems.

Understanding the Scale and Nature of Youth Migration

- Magnitude: Nearly 29% of India’s population are migrants; 89% originate from rural areas.

- Age Profile: Over half of all migrants are aged 15–25, indicating the loss of India’s most productive demographic.

- Pandemic Exposure: The 2020 Covid-19 lockdown forced 40 million workers to return home, revealing the fragility of informal urban employment.

- Gender Dynamics: Men migrate mainly for work, while 86.8% of women migrate due to marriage, reflecting persistent social norms.

- Socio-economic Profile: Higher migration rates among SC, OBC, and low-income groups show distress-driven mobility.

Drivers of Youth Migration from Rural India

a. Rural Employment Deficit

- Limited non-farm jobs; 49% migrants work as daily wagers and 39% in temporary industrial roles.

- Low returns from agriculture due to fragmented landholdings and climate exposure.

b. Education–Employment Mismatch

- Rural education lacks industry-relevant skills.

- Graduate unemployment exceeds 15% (CMIE 2024), indicating inadequate employability.

c. Income and Infrastructure Gaps

- Rural incomes fail to meet basic needs.

- Weak connectivity, inadequate credit access, and poor logistics hinder local enterprise formation.

d. Urban Pull Factors

- Cities offer perceived opportunities, higher wages, and mobility.

- However, migrants face unsafe housing, exploitation, and precarious informal jobs—88% lack social security.

Impact of Migration on Rural and Urban Landscapes

a. Urban Challenges

- Overcrowding, pollution, rising pressure on housing and infrastructure.

- Growth of slums in megacities like Delhi and Mumbai.

b. Rural Depopulation

- Loss of youth weakens agricultural productivity and local governance.

- Declining rural social capital affects community cohesion.

c. Social and Psychological Effects

- Family separation leads to stress, anxiety, and economic insecurity among dependents.

- Women migrants rarely enter the workforce, deepening gender gaps.

Policy Interventions and Initiatives

- MGNREGA ensures wage support during lean seasons, reducing distress migration.

- DDU-GKY, PMKVY provide vocational training to improve employability.

- PM-Mudra, Start-Up India, SVEP encourage rural entrepreneurship.

- 10,000 FPO initiative strengthens farmer collectives and value chains.

- BharatNet, PMGSY, rural BPOs expand digital and physical connectivity.

Way Forward: Reimagining Rural Education and Ecosystems

a. Integrating Education with Local Economies

- Embed vocational, digital, and agri-tech skills into rural curricula.

- Link schools and colleges to local enterprises and industries.

b. Diversifying Rural Non-Farm Sectors

- Develop employment in handicrafts, food processing, logistics, renewable energy, and agri-tourism.

c. Building Digital Ecosystems

- Invest in 5G connectivity, e-commerce platforms, tele-work hubs, and digital service centres.

d. Encouraging Local Entrepreneurship

- Promote success stories like Raigad’s BalaramBandagale to inspire reverse migration and rural innovation.

e. Strengthening Social Protection

- Ensure universal portability of PDS, health insurance, and pensions for mobile workers.

Conclusion

India must shift from a model where migration is a compulsion to one where it becomes a choice. Strengthening rural education, diversifying local economies, and empowering youth with market-ready skills can address structural causes of migration. A balanced rural–urban development framework—anchored in employment-linked learning, digital connectivity, and entrepreneurship—will help revitalise rural India and support inclusive, sustainable growth.

India’s Renewable Energy Transition: From Expansion to System Strength

- 27 Oct 2025

In News:

India’s renewable energy journey has evolved from an era of rapid capacity expansion to one focused on creating a stable, resilient, and system-integrated clean energy ecosystem. With a target of 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030, the country is moving from quantity to quality—shifting from mere capacity addition to building institutional, technical, and infrastructural strength capable of sustaining long-term decarbonisation.

Progress and Current Landscape

Over the past decade, India’s renewable energy capacity (excluding large hydro) has grown from around 35 GW in 2014 to over 197 GW in 2025, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing clean energy markets. The country continues to add 15–25 GW annually, driven by solar, wind, and hybrid installations. However, this phase of “rapid expansion” has revealed structural challenges — inadequate grid capacity, financing gaps, and the need for skilled manpower — necessitating a pivot toward “capacity absorption” and system integration.

From Speed to System Strength

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has emphasized that India’s renewable growth story is entering a new phase centered on system reliability, grid integration, and financial discipline. The focus now lies in synchronising renewable generation with transmission infrastructure, market mechanisms, and energy storage.

India’s grid is being reimagined through a ?2.4 lakh crore Transmission Plan for 500 GW, connecting renewable-rich states like Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Ladakh with industrial and urban demand centers. The Green Energy Corridors and planned High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission lines are expected to unlock over 200 GW of new capacity. The CERC’s 2025 General Network Access (GNA) regulations, introducing dynamic “solar-hour” and “non-solar-hour” access, will further optimise grid use and reduce congestion.

Building Institutional and Human Capacity

Capacity building in renewable energy involves strengthening human, institutional, and technical systems to manage grid variability, storage integration, and emerging technologies like offshore wind and green hydrogen. Institutions such as the National Institute of Solar Energy (NISE) and State Nodal Agencies (SNAs) are training engineers and regulators, while international collaborations with IRENA and GIZ are enhancing India’s technical knowledge base.

At the policy level, reforms such as Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes for solar modules, domestic content requirements, and duties on imported cells are deepening India’s manufacturing ecosystem, reducing import dependence, and enhancing competitiveness.

Innovation and Market Mechanisms

India’s renewable transition is increasingly driven by hybrid projects, Round-the-Clock (RTC) renewable energy, battery energy storage systems (BESS), and Virtual Power Purchase Agreements (VPPAs). These innovations ensure dispatchable power, attract private capital, and strengthen market-based renewable trading. Additionally, the National Green Hydrogen Mission is linking renewables to industrial decarbonisation, while distributed solar and agrovoltaic projects under PM Suryaghar and PM KUSUM are expanding rural participation in the clean energy transition.

Challenges and the Way Forward

India faces challenges including skill shortages, limited training infrastructure, financing constraints, and coordination gaps among multiple agencies. Rapid technological evolution demands continuous upskilling and institutional flexibility. Financial reforms, transmission readiness, and greater private sector participation will be key to sustaining the current momentum.

Conclusion

India’s renewable energy story is maturing—from a race for capacity to a strategy for endurance. Policy focus has shifted from expansion to integration, ensuring that the next growth phase is more stable, dispatchable, and sustainable. By aligning infrastructure, innovation, and institutions, India is laying the foundation for a resilient 500 GW clean energy system by 2030, driving its march toward Viksit Bharat and global climate leadership.

16th BRICS Summit 2025

- 26 Oct 2025

In News:

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi attended the 16th BRICS Summit, hosted by Russia in Kazan, under the theme “Strengthening Multilateralism for Just Global Development and Security.”

- The summit brought together leaders from Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, alongside newly inducted members such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, reflecting the bloc’s expanding global footprint.

Background and Evolution of BRICS

- The BRICS grouping originated as BRIC in 2006 following the St. Petersburg meeting between Russia, India, and China, and was later formalized at the Yekaterinburg Summit (2009).

- South Africa joined in 2011, transforming BRIC into BRICS.The most recent expansion in 2024 added five new members, representing a major step toward inclusivity and a stronger collective voice for the Global South.

Initially comprising 42% of the world’s population, 30% of global land area, 23% of GDP, and 18% of global trade, the expanded BRICS seeks to reshape global economic governance and reduce dependence on Western-led institutions.

Objectives and Role

The alliance aims to:

- Promote reform of multilateral institutions such as the UN, IMF, and World Bank to reflect contemporary global realities.

- Foster economic cooperation, technology sharing, and sustainable development.

- Strengthen South-South cooperation and enhance the collective influence of emerging economies in global decision-making.

- Advocate a multipolar world order grounded in equity and mutual respect.

Key Outcomes and Agenda of the 16th Summit

The Kazan summit focused on:

- Financial Independence from Western Systems: Members discussed reducing reliance on the US dollar and the SWIFT network, particularly after sanctions on Russia post-Ukraine conflict.

Countries are increasingly exploring local currency settlements, currency swaps, and building alternative payment systems. - Economic and Development Cooperation: Review of the functioning of the New Development Bank (NDB), which has financed projects worth billions in renewable energy, infrastructure, and social sectors.

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), with a reserve pool of $100 billion, continues to serve as a financial safety net. - Multilateral Reform and Climate Action: Discussions focused on reforming global institutions, promoting resilient supply chains, and strengthening collective action against climate change.

- Technology and Innovation: Members emphasized cooperation in science, innovation, and digital connectivity, enhancing research partnerships through the BRICS Science, Technology, and Innovation Framework.

India’s Priorities

Prime Minister Modi highlighted India’s role as a bridge between the Global South and developed economies. India’s agenda included:

- Strengthening reformed multilateralism and inclusive growth models.

- Deepening economic and technological collaboration within the bloc.

- Promoting people-to-people exchanges and cultural cooperation to enhance mutual understanding.

The visit also reinforced the Special and Privileged Strategic Partnership between India and Russia, marking PM Modi’s second visit to Russia in 2025.

Kazan: Symbolism and Significance

- The summit venue, Kazan, often referred to as Russia’s “third capital”, represents the country’s multi-ethnic and multi-religious identity.

- Located at the confluence of the Volga and Kazanka rivers, Kazan is the capital of Tatarstan and a thriving centre of petrochemicals, IT, and defence industries.

- Its diverse cultural fabric—home to both Orthodox cathedrals and Islamic mosques—embodies Russia’s pluralism and outreach to the Islamic world.

Challenges Ahead

Despite its achievements, BRICS faces internal and external challenges:

- Economic asymmetry among members, with China’s dominance occasionally causing unease.

- Geopolitical frictions, particularly between India and China, complicate consensus-building.

- Slow institutional reforms due to entrenched global power structures.

- Divergent foreign policy orientations toward the West among members.

Conclusion

The 16th BRICS Summit in Kazan reaffirmed the bloc’s commitment to a multipolar, equitable, and inclusive global order.

By advancing financial autonomy, technological cooperation, and institutional reform, BRICS continues to evolve as a platform for the Global South to assert its collective voice.

For India, it remains a vital forum to shape global governance, enhance strategic partnerships, and strengthen its vision of “VasudhaivaKutumbakam”—the world as one family.

Labelling AI-Generated Content in India: Towards Responsible Digital Governance

- 25 Oct 2025

In News:

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) has proposed amendments to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, mandating the labelling and disclosure of AI-generated content on social media platforms. The move comes amid growing public concern over deepfakes and synthetic media, which have begun to challenge democratic discourse, individual privacy, and digital trust.

The Rise of AI-Generated Content and Deepfake Concerns

India is experiencing a rapid surge in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for content creation across entertainment, advertising, and online communication. However, this technological boom has also led to the proliferation of deepfakes — hyper-realistic videos, images, and audio clips generated by AI that mimic real individuals or events.

The issue gained national prominence in 2023, when a manipulated video of a popular actor went viral, prompting outrage and prompting Prime Minister Narendra Modi to call deepfakes a new “crisis.” These incidents have exposed how synthetic content can be weaponised for political propaganda, misinformation, financial fraud, and reputational harm.

Key Provisions of the Draft Rules

The proposed amendments introduce a comprehensive framework to enhance transparency and accountability in digital content creation:

- Mandatory Self-Declaration:Users uploading content on platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, or X (formerly Twitter) must declare whether their material is AI-generated or synthetic.

- Dual Labelling Mechanism:

- Embedded Label: AI-generated visuals and audio must carry a visible watermark or label covering at least 10% of the surface area or duration.

- Platform-Level Label: A visible disclaimer will appear wherever such content is displayed online.

- Platform Accountability:If users fail to disclose synthetic content, platforms must proactively detect and label it using AI-based detection tools. Non-compliance could lead to loss of safe harbour protection under Section 79 of the IT Act, making intermediaries legally liable for misinformation.

- Metadata Requirement:AI-generated material must include a permanent, traceable metadata identifier embedded at the time of creation to ensure accountability.

- Scope of Application:The rule extends beyond social media to AI content generation tools like OpenAI’s Sora and Google’s Gemini, requiring built-in watermarking mechanisms.

Rationale and Policy Objectives

The policy aims to ensure that users in a democracy can distinguish between authentic and synthetic content. By mandating labelling and traceability, the government seeks to curb misinformation, protect democratic integrity, and uphold public trust in the digital ecosystem.

The ministry’s note emphasizes that AI-generated misinformation poses risks to national security, elections, and social stability, making proactive governance essential. Previously, such misuse was addressed under general impersonation and fraud provisions of the IT Act, 2000, but the evolving sophistication of generative AI tools now demands specific regulatory safeguards.

Global Context

India’s initiative aligns with global best practices.

- China (2025): Introduced mandatory AI labelling for deepfakes, voice synthesis, and chatbots with visible and hidden watermarks.

- European Union: Under its AI Act, mandates user notification when interacting with AI systems.

- United States: Developing federal standards for content authenticity and AI watermarking.

By adopting a binding legal framework, India positions itself among the early regulators of generative AI, setting a precedent for responsible innovation.

Implementation Challenges and the Way Forward

While the proposal has been broadly welcomed, challenges persist. Detecting AI-generated content across diverse languages and formats requires sophisticated detection infrastructure. Excessive compliance burdens may also affect startups and smaller creators in India’s expanding $12 billion AI ecosystem.

The government has invited public and industry feedback until November 6, 2025, signaling openness to iterative policy design. Successful implementation will depend on multi-stakeholder cooperation, technological innovation, and digital literacy among users.

Conclusion

The proposed amendments mark a decisive shift in India’s digital governance—from reactive moderation to preventive transparency. By mandating AI content labelling, India aims to balance technological innovation with ethical responsibility, ensuring that the age of artificial intelligence strengthens rather than undermines truth, democracy, and public trust.

Scheme to Attract ‘Star Faculty’ Amid Global Academic Shifts

- 24 Oct 2025

In News:

India is formulating an ambitious new scheme to attract Indian-origin “star faculty” and researchers working in global universities to return and contribute to its domestic research and innovation ecosystem. The initiative, under discussion between the Principal Scientific Adviser’s Office, the Department of Higher Education, and the Departments of Science and Technology (DST) and Biotechnology (DBT), reflects the government’s push to position India competitively in the global race for scientific and academic excellence.

Background: India’s Research Landscape

- India has a strong tradition in science and higher education through premier institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs), and national laboratories under the DST and DBT. However, the country faces persistent challenges in retaining and attracting top global talent.

- India’s R&D expenditure remains around 0.7% of GDP, much lower than that of the U.S. (2.8%) and China (2.4%). Coupled with bureaucratic hurdles, modest salaries, and limited research autonomy, these factors have led to a steady outflow of skilled scientists and academics, often referred to as “brain drain.”

- Existing programmes such as the Visiting Advanced Joint Research (VAJRA) Faculty Scheme, Ramanujan Fellowship, and Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship have attempted to link overseas Indian scholars with domestic institutions. However, participation has remained limited, prompting the need for a more comprehensive and long-term mechanism.

Key Features of the Proposed Scheme

The Star Faculty Scheme seeks to attract established Indian-origin researchers with strong academic and scientific credentials to work full-time or for extended periods in Indian institutions.

1. Targeted Recruitment:The initiative will focus on 12–14 strategic areas in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) deemed vital for national capacity-building.

2. Financial and Institutional Incentives:Returning scholars are likely to receive substantial one-time set-up grants to establish laboratories and research teams. Institutions like the IITs have expressed support for providing operational flexibility and research autonomy.

3. Red-Carpet Ecosystem:The scheme aims to minimize bureaucratic delays by offering streamlined processes for housing, administrative support, and project funding. Experts emphasize that beyond salaries, a “red-carpet” experience—ease of living and working—is critical to attracting global talent.

4. Collaborative Networks:It will promote inter-institutional linkages between Indian and foreign universities, ensuring long-term collaboration rather than short-term exchanges.

5. Light-Touch Oversight and IP Clarity:A balanced governance framework will ensure academic freedom, transparent intellectual property ownership, and minimal reporting burdens, aligning with global research practices.

Global Context

The initiative comes amid significant shifts in global academia. In the United States, policies like the “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education” under the Trump administration have tightened regulations on international students, race-based admissions, and university autonomy. Critics view these as constraints on academic freedom, prompting uncertainty among foreign faculty—including those of Indian origin.

Simultaneously, Europe is moving to enshrine academic freedom in law, while China and Taiwan continue to expand well-funded recruitment drives to attract overseas researchers. India’s new scheme aims to leverage this shifting academic landscape to bring back its global talent pool.

Structural Challenges

Experts highlight that India’s ability to compete globally will depend on addressing systemic issues:

- Non-competitive pay: A full professor in India earns roughly USD 38,000 annually, compared with USD 130,000–200,000 in the U.S. and USD 100,000 in China.

- Infrastructure gaps: Many universities still lack advanced laboratories and research autonomy.

- Bureaucratic hurdles: Lengthy approval processes discourage international collaboration.

The new programme aims to overcome these through multi-year appointments, flexible tenure, and transparent evaluation mechanisms.

Way Forward

If executed effectively, the Star Faculty Scheme could reverse the brain drain, strengthen India’s knowledge economy, and foster innovation-led growth. It can bridge the gap between academia and industry, promote technology transfer, and develop globally connected research ecosystems.

By offering world-class conditions, trust-based governance, and institutional flexibility, India has the opportunity to reimagine its academic landscape, positioning itself as a global hub for scientific talent and innovation in the 21st century.

Status of Elephants in India: New Census Establishes a Scientific Baseline for Conservation

- 23 Oct 2025

In News:

The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has released its report titled “Status of Elephants in India”, marking a new chapter in the country’s elephant conservation efforts. The study estimates 22,446 elephants across four major landscapes — the first time a DNA-based census method has been used. Although the figure appears lower than the 2017 estimate of 29,964 elephants, experts clarify that this does not represent a population decline but a fresh scientific baseline for future monitoring.

Evolution of Elephant Population Estimation in India

India’s elephant counts have evolved significantly since the first census in 1929 in the then United Province (now Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand). Early surveys relied on direct visual counts and averaging of sightings. With the launch of Project Elephant in 1992, the estimation process became more structured, with five-yearly assessments using methods such as total count, dung count, and transect sampling.

However, since different States adopted varied techniques, results were often inconsistent and incomparable. To overcome this, synchronised elephant censuses were conducted in 2005, 2010, and 2017 using uniform methods like total count and line transect dung count, but observer bias and overcounting remained major issues.

Recognising these limitations, India adopted a new scientific framework under the Synchronous All-India Elephant Estimation (SAIEE) 2021–25, shifting from visual to genetic sampling for more accurate and comparable results.

SAIEE 2021–25: A Scientific Overhaul

The SAIEE 2021–25 represents the most comprehensive and methodologically advanced elephant census in India. The country was divided into 100 sq. km cells, further split into 4 sq. km grids, each uniquely coded to ensure spatial accuracy. Enumerators covered over 6.6 lakh km, surveying nearly 1.9 lakh transects, and collected 21,056 dung samples for DNA extraction.

The census was carried out in three phases:

- Field data collection on animal signs, dung, vegetation, and human disturbances.

- Habitat and human impact assessment, including forest cover and patch size.

- Spatial abundance modelling using habitat and human interface data.

This shift to DNA-based identification eliminates duplication errors, allowing scientists to create a uniform national baseline for long-term monitoring and conservation.

Findings: The Landscape of Elephants

The report identifies four major elephant-bearing regions in India:

- Western Ghats (Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu) – The strongest habitat, hosting 11,934 elephants (53%), with Karnataka alone having 6,013.

- North Eastern Hills and Brahmaputra Flood Plains – About 22% of the national population, led by Assam with 4,159 elephants.

- Shivalik Hills and Gangetic Plains – Around 9%, mostly in Uttarakhand.

- Central India and Eastern Ghats – About 8%, with Odisha as a key habitat.

This highlights the Western Ghats as India’s most critical elephant stronghold, while the Northeast remains vital for transboundary populations.

Emerging Challenges: Fragmentation and Conflict

The report warns that habitat fragmentation due to commercial plantations, mining, linear infrastructure, and encroachments is severely impacting elephant movement. This has triggered increasing human-elephant conflict, as herds venture into new areas in search of food and connectivity.

In Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala — which together host the majority of India’s elephants — conflicts have led to hundreds of human and elephant fatalities. Similar patterns are emerging in Andhra Pradesh and parts of central India, where elephants have recolonised regions after nearly two centuries.

Conservation Outlook

Experts emphasise that habitat connectivity and coexistence must be central to future conservation strategies. The new DNA-based baseline offers a reliable foundation for policy interventions, habitat restoration, and conflict mitigation.

Community participation, awareness programmes, and integration of Elephant Corridors under Project Elephant are essential to ensure long-term survival of Elephas maximus in India.

Conclusion

India’s transition to a DNA-based elephant census marks a scientific milestone in wildlife monitoring. While the numbers suggest a smaller population than before, the shift represents a more precise and globally aligned approach to conservation. With over half of Asia’s elephants residing in India, the findings of the WII’s study underscore an urgent need to balance development with ecological sensitivity, ensuring that India’s national heritage animal continues to thrive in its natural habitats.

Government’s Strategy to Boost Defence Exports and Domestic Manufacturing

- 22 Oct 2025

In News:

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh recently announced the government’s target to expand India’s defence manufacturing ecosystem to a valuation of ?3 lakh crore and enhance defence exports to ?50,000 crore by 2029.This marks a significant step in India’s vision of transforming from the world’s largest arms importer to a global defence manufacturing and export hub.

About the Initiative

The plan represents a strategic roadmap to strengthen India’s indigenous defence production base while increasing global competitiveness. It aligns with the objectives of Atmanirbhar Bharat and Make in India initiatives in the defence sector.

Key Features and Focus Areas

1. Private Sector Integration

- Encouraging partnerships between private defence manufacturers, Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), and Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs).

- Collaboration with foreign Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to facilitate joint ventures, co-development, and technology transfer.

- Promoting participation in the Defence Industrial Corridors in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu to attract domestic and foreign investment.

2. Indigenisation of Defence Platforms

- Expanding indigenous production of major systems such as:

- LCA Tejas fighter aircraft

- Akash surface-to-air missiles

- Pinaka multi-barrel rocket launchers

- Advanced Light Helicopters (ALH) and Arjun tanks.

- Focus on import substitution through locally developed components, sensors, and sub-systems.

3. Policy and Regulatory Reforms

- Simplification of defence procurement procedures (DPP) and Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) to ensure faster clearances.

- Streamlined export licensing and authorisation through a single-window system.

- Incentivisation under Make-I, Make-II, and iDEX (Innovations for Defence Excellence) programmes.

- Enhanced funding for start-ups and MSMEs in defence innovation under the Technology Development Fund (TDF).

4. Skill Development and Research

- Establishment of specialised defence education and skilling institutes, such as Symbiosis Skills and Professional University, to build a trained workforce.

- Promotion of R&D collaboration between academia, industry, and DRDO to accelerate innovation in next-generation technologies like AI, robotics, and autonomous systems.

5. Operational Validation

- Indigenous systems have been successfully deployed in real operations—such as Operation Sindoor, which demonstrated the combat readiness and reliability of domestically produced defence equipment.

- Strengthening of quality assurance and field validation processes to enhance global trust in Indian defence products.

Strategic Significance

- Economic Growth:The initiative will boost industrial output, exports, and employment, contributing to India’s defence industrial self-reliance and GDP growth.

- Global Competitiveness:Positions India as a net defence exporter, catering to friendly nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- National Security:Reduces dependence on foreign arms imports and enhances strategic autonomy in critical technologies.

- Technological Innovation:Encourages indigenous innovation and the development of dual-use technologies benefiting both defence and civilian sectors.

- Geopolitical Leverage:Expanding defence exports strengthens India’s diplomatic ties through defence diplomacy and builds strategic partnerships with friendly nations.

Challenges Ahead

- Need for faster project implementation and clearer export procedures.

- Addressing R&D funding gaps and improving private sector participation.

- Ensuring competitive pricing and quality to meet global standards.

- Streamlining coordination among MoD, DRDO, DPSUs, and private players.

Way Forward

- Promote joint ventures with global defence majors to enhance technology absorption.

- Strengthen testing and certification infrastructure to meet international benchmarks.

- Expand defence offset policies to attract advanced technologies.

- Encourage defence start-ups and innovation clusters for rapid prototyping and scalable production.

Conclusion

India’s ambitious target to achieve ?3 lakh crore in defence production and ?50,000 crore in exports by 2029 reflects a paradigm shift toward self-reliance, innovation, and global competitiveness in defence manufacturing.

With sustained policy reforms, technological investment, and industry-academia synergy, India is well-positioned to emerge as a reliable global supplier of advanced defence systems and a pillar of regional security.

Poverty Measurement in India: Revisiting the Rangarajan Line and the Rise of Multidimensional Poverty

- 21 Oct 2025

In News:

The debate on poverty measurement in India has gained renewed significance with the Reserve Bank of India’s Department of Economic and Policy Research (DEPR) updating state-wise poverty estimates using the 2022–23 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES). This marks the first major recalibration of the C. Rangarajan Committee’s poverty line, originally formulated in 2014, and reflects shifting paradigms in assessing deprivation in India.

Revisiting the Rangarajan Framework

The Rangarajan Committee was tasked with redefining poverty beyond the earlier Tendulkar methodology. It fixed the poverty line at ?972 per capita per month in rural India and ?1,407 in urban areas (2011–12 prices), categorising about 29.5% of the population as poor. Its poverty basket focused on minimum nutritional requirements along with basic spending on health, education, fuel, clothing, and rent. Unlike later approaches, it offered a strict consumption-based benchmark rooted in monetary expenditure.

Updated Poverty Trends: State-wise Insights

RBI economists reconstructed poverty lines for 20 major states based on HCES 2022–23 data using a new price index aligned with the original poverty line basket rather than Consumer Price Index weights. The findings highlight remarkable improvements, with major reductions observed in traditionally backward states:

- Odisha: Rural poverty fell from 47.8% (2011–12) to 8.6% (2022–23)

- Bihar: Urban poverty dropped from 50.8% to 9.1%

- Kerala: Rural poverty declined to 1.4%; Himachal Pradesh’s urban poverty fell to 2%

- Lowest poverty levels: Rural Himachal Pradesh (0.4%) and urban Tamil Nadu (1.9%)

- Highest poverty levels: Chhattisgarh (25.1% rural; 13.3% urban)

These transformations reflect improved rural infrastructure, livelihood programmes, PDS reforms, and social transfers. Yet persistent poverty in central Indian states underscores uneven development and structural gaps in employment quality, agrarian distress, and welfare delivery.

Methodological Continuity and Debate

Poverty estimates vary sharply across institutions, illustrating the sensitivity of measurement frameworks:

- SBI (2023–24): ~4–5% poverty

- World Bank (2022): 10.2% poverty in 2019

- IMF (2022): 0.8% in 2019 (including food transfers)

These disparities stem from differing inflation adjustments, survey datasets, and treatment of welfare subsidies. They also fuel a longstanding debate: can income-based poverty capture human deprivation comprehensively, especially in a transforming economy with evolving consumption patterns?

Shift to Multidimensional Poverty

Official focus has now decisively shifted to multidimensional poverty aligned with SDG frameworks. India’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) evaluates deprivation across twelve indicators spanning health, education, and living standards. According to NITI Aayog (2024), 24.82 crore people exited multidimensional poverty between 2013–14 and 2022–23, reducing MPI from 29.17% to 11.28%. This highlights the impact of welfare architecture—PDS expansion, Ujjwala, Saubhagya, Jal Jeevan Mission, Swachh Bharat, and financial inclusion.

Way Forward

- Regular poverty line updates reflecting new consumption patterns and regional price realities

- Integration of income and multidimensional metrics for balanced welfare planning

- Timely survey releases and transparent data to strengthen evidence-based policymaking

- Targeted interventions for lagging states like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and parts of UP

- Leveraging digital delivery systems to minimise leakages and enhance inclusivity

Conclusion

India’s poverty trajectory reflects a dual narrative—sharp improvements driven by welfare provisioning and growth, yet uneven progress across regions and methodological contestation. While the Rangarajan line continues to serve as a benchmark for monetary poverty, the dominance of multidimensional metrics signals a shift towards understanding deprivation as a matter of human capability, not merely income. Ensuring sustained and equitable poverty reduction will require methodological rigor, policy innovation, and heightened focus on lagging geographies to achieve inclusive development.

Google’s $15 Billion AI Data Centre in Andhra Pradesh

- 18 Oct 2025

In News:

Google’s announcement of a USD 15-billion investment to establish an Artificial Intelligence (AI) data centre in Visakhapatnam marks a transformational moment in India’s digital infrastructure landscape. The initiative, the largest single investment by Google in India, comes amid a geo-economic context of recalibrating India-US relations and the government’s emphasis on technological self-reliance and swadeshi digital systems. The project positions India as an emerging hub in global AI capability and computing power.

Why AI Data Centres Matter

AI-focused data centres differ fundamentally from conventional facilities. While traditional data centres are built around CPU-based servers to support cloud storage, websites, and enterprise applications, AI data centres rely on high-performance GPUs to handle data-heavy and compute-intensive workloads such as generative AI, advanced analytics, image/video processing, and deep-learning models. This makes them significantly more power-intensive and infrastructure-demanding, requiring robust energy supply and advanced cooling systems.

According to estimates cited by Google, the Visakhapatnam AI hub is expected to add at least USD 15 billion to the US GDP between 2026 and 2030 through increased AI adoption and cloud-driven activity, demonstrating the cross-border economic impact of such investments.

Partnerships and Green Infrastructure

The facility is being developed in partnership with AdaniConneX and Airtel, leveraging the same backbone used for Google’s global platforms like Search, YouTube, and Workspace. The project includes building a major subsea cable landing station, linking eastern India to Google’s expansive global cable network, enhancing international data routes and reducing latency.

A key dimension of the partnership lies in sustainable power and energy independence. AdaniConneX, a joint venture between Adani Enterprises and EdgeConneX, will provide 100% clean energy, supported by new transmission lines, renewable generation, and energy storage facilities in Andhra Pradesh. This aligns with India’s climate commitments and enhances grid resilience.

Economic Impact and Capacity Expansion

India’s data centre industry, currently valued at ~USD 10 billion with USD 1.2 billion in FY24 revenue, is projected to add 795 MW of capacity by 2027 — reaching 1.8 GW. Google’s project alone is expected to generate nearly 1.88 lakh direct and indirect jobs, strengthening regional development and high-skilled employment.

However, high capital costs and limited job intensity remain policy concerns. Approximately 40% of capex in data centres goes towards electrical systems, and 65% of operating costs are attributed to electricity, with ~?60–70 crore required per MW of capacity. This necessitates a careful assessment of incentives and long-term strategic benefits.

Energy Security and the Nuclear Option

The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that global data-centre electricity demand may double by 2026, raising questions around sustainability. While renewable energy remains the mainstay, its intermittency has prompted policy consideration of nuclear energy as a round-the-clock clean power source — a trend already visible in the United States and now emerging in India’s energy strategy.

Conclusion

Google’s AI hub in Visakhapatnam represents a strategic convergence of digital infrastructure, clean-energy innovation, and global technological cooperation. For India, it underscores the dual challenge of expanding digital capability while ensuring energy security and environmental sustainability. The success of this initiative will influence India’s journey toward becoming a global digital superpower underpinned by resilient, sovereign, and sustainable compute ecosystems.

India’s First DNA-Based Elephant Census: Population Declines, New Scientific Baseline Established

- 17 Oct 2025

In News:

- India has released the results of its first-ever DNA-based elephant population assessment under the Synchronous All-India Elephant Estimation (SAIEE) 2021–25.

- The report estimates 22,446 wild elephants, marking an 18% decline from the 2017 figure of 27,312. However, the government stresses that the numbers are not directly comparable due to a shift to a more advanced, genetic mark-recapture methodology, establishing a new population baseline.

Significance of Elephants in India

- India hosts over 60% of the global Asian elephant population, making it critical to the species’ global survival.

- Elephants are Keystone species, maintaining forest ecosystem health.

- They are deeply woven into Indian cultural, religious, and ecological heritage.

Distribution

Elephants in India inhabit four major landscapes:

|

Region |

Estimated Population (2025) |

|

Western Ghats |

11,934 (largest population) |

|

North Eastern Hills & Brahmaputra Floodplains |

6,559 |

|

Shivalik Hills & Gangetic Plains |

2,062 |

|

Central India & Eastern Ghats |

1,891 |

Top States (2025)

- Karnataka: 6,013

- Assam: 4,159

- Tamil Nadu: 3,136

- Kerala: 2,785

- Uttarakhand: 1,792

- Odisha: 912

These states collectively support over 80% of India’s elephant population.

How the DNA-Based Census Was Conducted

This was India’s most comprehensive elephant survey to date, combining:

- DNA fingerprinting of dung samples

- Satellite mapping

- Ground-based habitat surveys

Key Technical Inputs

- ~21,000+ dung samples collected across 20 states

- 4,065 individual elephants genetically identified

- Forests divided into 100 sq km grids, further sub-divided for finer sampling—adapted from India’s tiger census model

- Survey covered 6.7 lakh km of forest trails and 3.1 lakh dung plots

This non-invasive method is statistically robust compared to earlier sighting-based estimates.

Key Findings

- Estimated Population: 22,446 (range: 18,255 – 26,645)

- Western Ghats largest stronghold

- Population decline observed, though partly attributed to more accurate methodology

- Significant habitat fragmentation and corridor disruption noted

Major Threats

- Habitat loss & fragmentation from agriculture, mining, infrastructure and linear projects

- Human-elephant conflict leading to casualties on both sides

- Poaching and retaliatory killings

- Disruption of migration corridors by rail lines, highways, power fences

- Invasive species and land-use change (especially Western Ghats and Northeast)

Legal Protection & Conservation Measures

- Status: Endangered (IUCN)

- Legal Protection: Schedule I — Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972; Appendix I — CITES

- Key Initiatives

- Project Elephant (1992)

- 101 Elephant Corridors Programme

- Gaj Yatra Awareness Campaign

- Use of technology: satellite tracking, GIS, camera traps, M-STRiPES-like monitoring

The government is now working on Project Elephant 2.0 to strengthen habitat connectivity and conflict mitigation through community-based conservation.

Significance of the New Baseline

- Establishes a scientific foundation for long-term population monitoring

- Enables integration of genetic, ecological & spatial data

- Aligns with global best practices in wildlife conservation

- Crucial for revising policies on corridor protection, land-use planning, and conflict reduction

2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences: Understanding Innovation-Driven Growth

- 16 Oct 2025

In News:

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences has been awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt for their seminal contributions to explaining how innovation drives long-term economic growth. Their work collectively answers a fundamental question in development economics: why has sustained growth become the norm in the last two centuries, despite millennia of stagnation? While Mokyr approaches the issue through economic history, Aghion and Howitt construct a formal model illustrating the dynamics of innovation and competition in modern economies.

Mokyr’s Framework: Useful Knowledge and Openness to Change

Joel Mokyr argues that economic stagnation persisted through most of human history because innovation lacked a strong scientific foundation. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, technological progress was primarily prescriptive—people knew how to produce goods but not why processes worked as they did. This limited systematic improvement.

The transformation began during the Scientific Revolution (16th–17th centuries) when controlled experimentation, measurement, and reproducibility became central to knowledge creation. This generated “useful knowledge”—a synergy of propositional (scientific principles) and prescriptive (practical techniques) knowledge. Examples include improvements in the steam engine driven by insights into atmospheric pressure and advancements in steel production based on understanding carbon reduction in iron.

However, knowledge alone was not sufficient. Societal openness to change, a hallmark of Enlightenment thought, enabled technological disruption. Acceptance of new ideas, weakening of entrenched elites, and institutional reforms—from the British Parliament curbing aristocratic privileges to society’s rejection of Luddite resistance to machinery—allowed innovations to diffuse widely. According to Mokyr, skills-based human capital and a culture supportive of disruption are crucial pillars of sustained growth.

Aghion–Howitt’s Creative Destruction Model

Drawing on Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction, Aghion and Howitt develop a rigorous macroeconomic model explaining how innovation displaces old technologies and firms, generating productivity gains. Their model shows that firms invest in research and development (R&D) to secure temporary monopoly power through patents. This monopoly incentivizes innovation, yet it is continually threatened by newer technologies. Thus, growth emerges from a constant cycle of competition, firm turnover, and technological leaps.

Importantly, their general equilibrium framework links household savings, financial markets, production decisions, and innovation incentives, demonstrating that micro-level disruptions are essential for macro-level stability. Empirical trends—such as high annual firm entry and exit rates in developed economies—support their argument.

Policy Implications

The Nobel findings highlight key contemporary debates:

- R&D Subsidies: Innovation has positive spillovers beyond private profit. Public funding can correct under-investment, but excessive subsidies risk waste where gains are marginal.

- Social Safety Nets: Creative destruction benefits economies but harms displaced workers and firms. A balanced welfare ecosystem ensures societies remain open to technological change.

- Skilling and Human Capital: To convert ideas into output, governments must invest in education, vocational training, and research ecosystems.

Conclusion

The 2025 Nobel laureates collectively establish that economic growth is neither automatic nor guaranteed—it is the result of science-based knowledge creation, institutional openness, and dynamic competition. For emerging economies like India, fostering innovation-driven growth requires strong research systems, regulatory flexibility, investment in human capital, and social policies that cushion transition shocks. Their work underscores that sustainable progress lies in embracing change, not resisting it.

India’s Grain-Driven Ethanol Transition: Shifting Paradigms in Biofuel Policy

- 15 Oct 2025

In News:

India’s ethanol blending programme, originally launched to reduce oil imports and stabilise the sugar industry, is undergoing a transformative shift. What began as a sugarcane-centric initiative has evolved into a grain-based ethanol ecosystem, reflecting structural changes in agricultural markets, energy policy, and rural industrialisation. For the first time, grain-derived ethanol—predominantly from maize—has surpassed sugarcane-based production, marking a pivotal moment in India’s biofuel sector.

Evolution of Ethanol Blending

The Ethanol Blending Programme (EBP) was initially designed to create additional revenue streams for sugar mills and ensure timely payments to cane growers. Early production relied on C-heavy molasses, a by-product of sugar extraction. Policy reforms in 2018 incentivised diversion of B-heavy molasses and even direct cane juice toward ethanol, raising supplies from 38 crore litres in 2013-14 to nearly 189 crore litres by 2018-19, and increasing blending levels from 1.6% to nearly 5%. This stabilised the sugar economy and boosted rural incomes.

Rise of Grain-Based Ethanol

A crucial turning point came when the government permitted ethanol production from grains such as maize, rice, and damaged foodgrains, offering differential pricing to attract investment. Grain-based distilleries rapidly expanded across Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and other states, with over ?40,000 crore invested in facilities capable of using multiple feedstocks.

By 2023-24, of the 672.49 crore litres supplied to Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs), almost 60% came from grains, with maize accounting for the largest share. In 2024-25, grain-based ethanol procurement is expected to reach 620 crore litres, with maize alone contributing about 420 crore litres. Drought-induced sugarcane shortages and more attractive prices—?71.86 per litre for maize-based ethanol versus ?57.97–65.61 per litre for cane-based routes—accelerated the shift.

Capacity and Policy Dynamics

India today hosts 499 distilleries with an annual ethanol capacity of 1,822 crore litres. Against a 20% blending target, OMCs sought 1,050 crore litres for 2025-26, but received offers exceeding 1,776 crore litres—signalling emerging overcapacity. While this capacity enhances energy security and reduces crude imports (over $160 billion annually), it introduces new challenges in balancing supply, food security, and price stability.

Challenges: Food Security, Sustainability, and Market Balance

India now faces a classic food-versus-fuel dilemma. Producing ~420 crore litres of maize ethanol consumes over 11 million tonnes of maize, nearly 26% of national output. With maize being vital for poultry and livestock feed, diversion to fuel can raise feed costs and food inflation. Similarly, viability of rice-based ethanol hinges on surplus FCI stocks—an uncertain variable.

Environmental concerns are also emerging. While ethanol reduces carbon emissions, grain-based production increases pressure on water, land, and fertiliser use, particularly in maize-growing regions.

Way Forward

Policy refinements are underway to ensure a balanced biofuel strategy. A dual-feedstock approach—leveraging both cane and grains—along with scaling second-generation (2G) biofuels from agricultural waste, is expected to drive future growth. Adequate stock monitoring, sustainable cultivation practices, and technological innovation will be critical for achieving the 20% blending target by 2025-26 without compromising food security.

Conclusion

India’s ethanol revolution demonstrates strategic economic diversification, rural industrialisation, and commitment to energy transition. However, sustaining this momentum requires calibrated policies aligning energy security with agricultural sustainability, food availability, and environmental stewardship—critical considerations for a resilient and self-reliant biofuel future.

Gender-Affirming Care (GAC)

- 14 Oct 2025

In News:

India has witnessed significant legal milestones in recognising the rights of transgender and gender-diverse persons, most notably the NALSA v. Union of India (2014) judgement affirming gender self-identification and the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. However, the lived reality of transgender communities remains marked by deep social exclusion, stigma, and poor health outcomes. Among these, mental health remains the most neglected dimension, despite clear evidence linking social affirmation and access to gender-affirming care (GAC) with substantial improvements in wellbeing.

The Mental Health Crisis

Transgender individuals face disproportionate psychological distress arising from discrimination, violence, marginalisation, and denial of identity. Recent national-level studies indicate that 31% of transgender persons in India have attempted suicide, nearly half before age 20. Rates of depression, anxiety, and self-harm are significantly higher than in the general population. Research globally—including evidence from JAMA Network Open (2023)—confirms that timely access to gender-affirming interventions markedly reduces gender dysphoria, suicidal ideation, and depression, while improving life satisfaction and functioning.

What Gender-Affirming Care Encompasses

Gender-affirming care is a continuum of social, medical, and psychological support that enables individuals to live in alignment with their gender identity. It ranges from basic respect for chosen names and pronouns to counselling, hormone therapy, and surgical interventions when desired. International bodies, including the World Health Organization, recognise GAC as medically necessary, not elective, owing to its direct link to mental and physical health. Importantly, GAC is rooted in dignity and self-determination—core to Article 21’s right to life and dignity under the Constitution of India.

Barriers to Access

Despite recognition in law, access to GAC in India remains severely limited:

- Scarce trained providers and absence of standardised national treatment protocols

- Financial barriers: surgeries costing ?2–?8 lakh and hormone therapies ?50,000–?70,000 annually

- Under-implementation of Ayushman Bharat TG Plus, with limited empanelled hospitals

- Stigma in healthcare settings leading to refusal of treatment or discriminatory behaviour

- Rising cases of unsupervised hormone use, causing serious health complications including organ damage

Policy blind spots also hinder progress; the absence of transgender-specific data in major surveys like NFHS and NSSO leads to exclusion from mainstream health planning and welfare schemes.

Societal and Health Consequences

When GAC is inaccessible, the consequences are profound—heightened mental illness, economic precarity, and social alienation. Research from Indian institutions such as TISS has documented widespread discrimination in healthcare settings, with 65% of trans youth reporting some form of refusal or mistreatment. Such systemic barriers reinforce cycles of poverty, homelessness, and deteriorating health.

Policy Priorities and Way Forward

Ensuring equitable access to gender-affirming care requires a rights-based, public health-driven framework. Key priorities include:

- Integrating GAC into Ayushman Bharat with free or subsidised access in public hospitals

- Establishing national clinical guidelines and training medical personnel in gender-affirming practice

- Strengthening trans-led community institutions for outreach, mental health support, and navigation

- Mandating inclusive insurance coverage for hormone therapy and surgeries

- Building robust data systems to guide policy and budget allocations

- Launching public sensitisation campaigns to combat stigma

- Replicating successful state models such as Tamil Nadu’s gender clinics and Kerala’s Transgender Cell

Conclusion

Gender-affirming care is fundamental to the right to health, dignity, and equality. India’s progress in legal recognition must now translate into accessible, affordable, and stigma-free health services. Achieving genuine mental health equity and social justice demands urgent integration of gender-affirming care into primary healthcare systems. Empowering transgender persons to live authentically is not merely a medical intervention—it is a constitutional and moral imperative for an inclusive, humane, and equitable India.

Credit Reforms to Deepen Financial Markets

- 13 Oct 2025

In News:

India’s journey toward Viksit Bharat 2047 hinges on simultaneously nurturing human capital and modernising financial institutions. Two recent developments reflect this integrated approach: the Viksit Bharat Buildathon 2025 and the Reserve Bank of India’s initiatives to strengthen financial markets and internationalise the rupee. Together, they illustrate India's twin strategy of empowering youth as innovation leaders while deepening economic capacity and regional influence.

Fostering a Culture of Innovation: Viksit Bharat Buildathon 2025

- The Viksit Bharat Buildathon, launched by the Ministry of Education in collaboration with NITI Aayog’s Atal Innovation Mission, is India’s largest school-level hackathon, engaging 1 crore students across classes 6–12.

- Aligned with NEP 2020, it aims to build problem-solving aptitude and innovation competencies from grassroots levels. Students work in teams to design prototypes based on four themes central to India’s development discourse—Atmanirbhar Bharat, Swadeshi, Vocal for Local, and Samriddh Bharat.

- The event adopts a phased structure: registrations (September), nationwide live build on 13 October 2025, and final evaluation by December. With Rs 1 crore award pool and dedicated mentorship from innovation networks and higher education institutions, it incentivises early exposure to experiential learning, creativity, and entrepreneurship. Importantly, it prioritises participation from Aspirational Districts, tribal belts, and frontier regions, promoting inclusivity in innovation ecosystems.

- By integrating rural and underserved communities, the initiative aligns with the principle of technology-enabled social justice and fosters an innovation-ready workforce. It positions schoolchildren not merely as future beneficiaries but as current contributors to nation-building—a step crucial for demographic dividend utilisation.

Rewiring India’s Financial System: RBI’s Strategic Reforms

Parallelly, the Reserve Bank of India has initiated significant policy reforms to bolster India’s financial depth and global standing. It has permitted banks to finance corporate mergers and acquisitions—a domain previously dominated by NBFCs—allowing formal banking channels to support corporate consolidation, expansion, and competitiveness. This move reflects confidence in banking sector resilience and recognises that scale and efficiency are essential for domestic firms in a globalising economy.

In a landmark regional diplomacy initiative, RBI has authorised Indian banks and their overseas branches to provide rupee-denominated loans to residents of neighbouring countries. This step supports rupee internationalisation, reduces dependence on the US dollar for regional transactions, and enhances India’s financial influence, especially amid global currency contestations.

Additional measures—such as raising the limit for loans against shares to Rs 1 crore, enabling investment of surplus Special Rupee Vostro Account balances in corporate bonds, and widening currency benchmarking—will deepen capital markets, enhance liquidity, and improve foreign participation confidence.

Conclusion

The Buildathon and RBI reforms, though sectorally distinct, serve a shared national objective: building a self-reliant, innovation-driven, globally confident India. While one invests in future innovators and inclusive talent pipelines, the other strengthens the institutional financial ecosystem needed to support economic expansion and regional leadership. Together, they represent India’s holistic developmental approach—nurturing minds, empowering markets, and globalising national capabilities in pursuit of Viksit Bharat.

‘Breathable Art’: Blending Creativity and Sustainability for Cleaner Air in Urban India

- 12 Oct 2025

In News:

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) recently inaugurated “Breathable Art” — an innovative living installation at Swarn Jayanti Park, Rohini, Delhi. Conceived under the ‘Breath of Change – Clean Air, Blue Skies’ campaign, the initiative aims to combine artistic expression with ecological functionality to promote awareness on air quality, sustainability, and urban environmental stewardship.

About the Initiative

- Breathable Art is a pioneering “living structure” created from air-purifying plants and eco-friendly materials.

- Sponsored by MoEFCC and supported by the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) and Delhi Development Authority (DDA), it forms part of the Environmental Information, Awareness, Capacity Building and Livelihood Programme (EIACP) under the Environment Education, Awareness, Research and Skill Development (EEARSD) scheme.

- The installation integrates art, science, and community engagement — transforming a public space into an interactive platform for environmental education.

- Visitors can scan QR codes placed around the installation to learn about the plants’ role in air purification and sustainable living practices. This interactive element aims to make environmental learning participatory and accessible.

Features and Ecological Role

The structure uses a mix of air-purifying plant species — such as Areca Palm, Bamboo Palm, Money Plant, Snake Plant, Spider Plant, Parijat, Peace Lily, Arrowhead, Weeping Fig, and Zigzag Plant. These species are recognized for their capacity to absorb harmful pollutants like formaldehyde and benzene, regulate humidity, and enhance oxygen concentration — particularly valuable during Delhi’s winter months when air quality deteriorates sharply.

By embedding these plants into an aesthetically designed structure, Breathable Art offers a passive yet effective solution to urban air pollution. It also enhances local biodiversity and contributes to microclimate regulation within its surroundings.

Community and Educational Dimensions

Beyond its environmental function, Breathable Art serves as:

- An Educational Hub: Hosting students, eco-clubs, and community members for awareness sessions on clean air and sustainable living.

- A Community Catalyst: Encouraging participation of Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), schools, and volunteers in maintaining and replicating such models across the city.

- A Strategic Urban Intervention: Targeting pollution hotspots to promote green urban aesthetics and inspire behavioral change.

This aligns with India’s broader approach of nature-based solutions for urban environmental management — emphasizing community participation, low-cost interventions, and local ecological resilience.

Significance and Way Forward

- Delhi, one of the world’s most polluted capitals, continues to face critical air quality challenges. Initiatives like Breathable Art highlight how creative, sustainable, and participatory approaches can complement policy-driven measures such as the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP).

- By merging environmental science with public art, the project redefines sustainability as a lived, experiential practice rather than a distant policy goal. It underscores the principle that environmental consciousness begins with individual action and community involvement.

- As urban India grapples with escalating pollution, Breathable Art serves as a replicable model for integrating ecological awareness into everyday spaces — inspiring cleaner, greener, and more mindful cities.

Conclusion:

Breathable Art is not merely an installation but a vision — where art, environment, and community converge to remind citizens that sustainability begins with a single breath. It symbolizes India’s evolving approach to environmental governance — creative, participatory, and rooted in harmony with nature.

India’s Mental Health Crisis: Towards a Unified and Inclusive Response

- 11 Oct 2025

In News:

Every year on October 10, the world observes World Mental Health Day to underscore the growing burden of mental disorders — now affecting over one billion people globally, or 13% of the world’s population. India mirrors this crisis, with a 13.7% lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and rising suicides — 1.71 lakh cases in 2023, including a concerning 65% increase in student suicides over the past decade.

Rising Mental Health Concerns

Globally, anxiety and depression account for two-thirds of all diagnosed mental disorders. Between 2011 and 2021, the number of people with mental disorders rose faster than the world’s population. In India, changing social structures, excessive internet and social media use, academic pressure, and hostile work environments have aggravated psychological distress, especially among the youth. Poor lifestyle habits, reduced family interaction, and economic uncertainty have further deepened the crisis.