Passive Euthanasia in India

- 30 Nov 2025

In News:

In a recent case, the Supreme Court directed the District Hospital, Noida, to constitute a Primary Medical Board to examine whether life-sustaining treatment can be withdrawn for a 32-year-old man in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) for over 12 years. The petition, filed by the patient’s father, sought passive euthanasia, not active intervention. The Court, while acknowledging the patient’s irreversible condition and total disability, reaffirmed that any decision must strictly follow the safeguards laid down in its earlier judgments, and sought a medical report within two weeks before taking a final call.

Understanding Euthanasia and Persistent Vegetative State

A Persistent Vegetative State (PVS) is a condition where higher brain functions such as awareness and cognition are irreversibly lost, while basic functions like breathing, circulation and reflexes continue.

Euthanasia refers to intentionally accelerating death to relieve suffering from an incurable condition and is broadly of two types:

- Active Euthanasia: Direct action to end life (illegal in India).

- Passive Euthanasia: Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, allowing natural death.

India permits only passive euthanasia, subject to strict legal and procedural safeguards.

Legal Position in India

Indian law does not recognise an unfettered “right to die” under Article 21, but the Supreme Court has interpreted the right to life to include the right to die with dignity in exceptional circumstances.

- Active euthanasia is prohibited and punishable under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, as culpable homicide or murder.

- Passive euthanasia is legally permissible under judicially evolved safeguards.

Key judicial milestones include:

- Aruna Shanbaug case (2011): Allowed withdrawal of life support for incompetent patients under court supervision.

- Common Cause case (2018): Recognised passive euthanasia and validated advance medical directives (living wills) for competent adults.

- 2023 modifications: Simplified procedures by reducing medical board size and experience requirements, and setting clear timelines to make the process workable.

Procedural Safeguards

The Supreme Court mandates a two-tier medical review:

- Primary Medical Board constituted by the hospital.

- Secondary Medical Board at the district level.

These boards assess the medical condition, irreversibility, and best interests of the patient. Judicial oversight ensures protection against misuse while respecting dignity.

Ethical Dimensions

The euthanasia debate reflects a tension between competing ethical principles:

- Arguments in favour emphasise autonomy, compassion, minimisation of suffering, and rational allocation of scarce medical resources.

- Arguments against stress the sanctity of life, the doctor’s duty of non-maleficence, risks of a slippery slope, and erosion of trust in medical ethics.

India’s approach attempts a middle path rejecting active killing while permitting dignified death in narrowly defined circumstances.

Global Perspective

Countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium permit both euthanasia and assisted suicide under strict laws, while others like Switzerland allow assisted suicide but prohibit active euthanasia. These variations show that euthanasia is shaped as much by societal values as by medical capability.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s direction to constitute a medical board reflects India’s cautious, dignity-centric approach to end-of-life decisions. By balancing compassion with safeguards, autonomy with ethics, and medical judgment with judicial oversight, India seeks to ensure that death, when inevitable, is humane rather than mechanical. As medical technology prolongs biological life, evolving jurisprudence on passive euthanasia will remain crucial to uphold constitutional morality, human dignity and ethical restraint.

Passive Euthanasia for Rabies Patients: SC to Hear Plea

- 16 Feb 2025

In News:

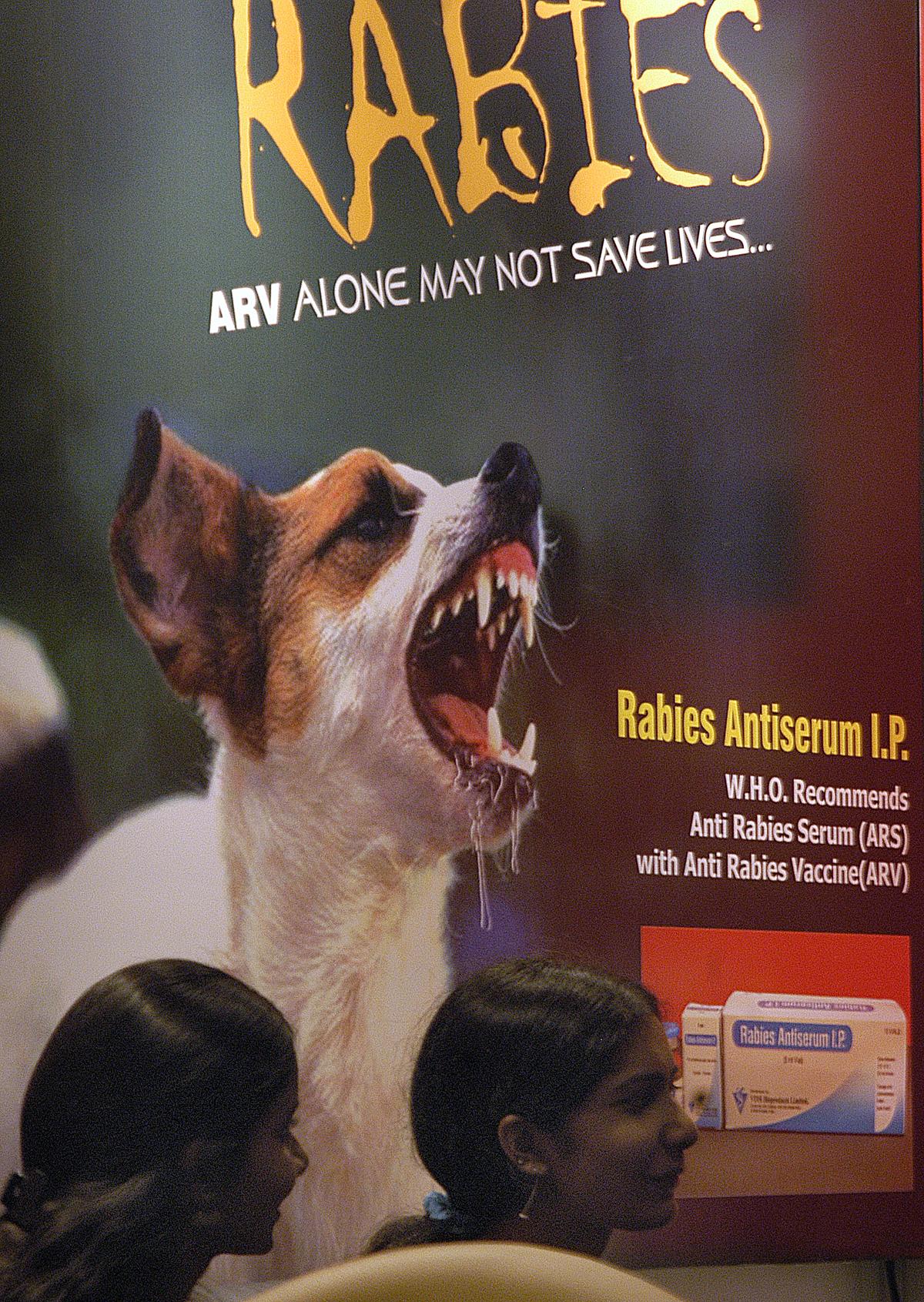

The Supreme Court of India has recently agreed to hear a plea seeking the right to passive euthanasia for rabies patients, citing the exceptional nature of the disease and the absence of a cure. The matter, listed for hearing after two weeks, is poised to test the scope and application of the 2018 passive euthanasia ruling under Article 21 of the Constitution.

Background of the Case

- The petition was filed by the NGO All Creatures Great and Small in 2019, challenging a Delhi High Court order (July 2019) which refused to classify rabies as an exceptional case warranting "death with dignity".

- The Supreme Court issued notice in January 2020 to the Centre and other stakeholders, seeking their response.

- On February 10, 2025, a bench of Justices B.R. Gavai and K. Vinod Chandran agreed to hear the matter after two weeks.

Grounds for the Plea

The NGO has urged the Court to lay down a specific protocol enabling terminally ill rabies patients or their guardians to opt for passive euthanasia under medical supervision. Key arguments include:

- Rabies has a 100% fatality rate once symptoms appear.

- The disease often leads to violent neurological symptoms, requiring patients to be tied or shackled to beds, stripping them of dignity and personal freedom.

- The intense suffering and irreversible nature of rabies, coupled with the lack of any effective treatment, makes it distinct from other terminal conditions.

- The plea seeks the creation of an exceptional legal category for rabies within the framework of the 2018 Supreme Court judgment.

Understanding Euthanasia in India

Definitions:

- Euthanasia literally means “good death” and refers to hastening death to relieve pain and suffering.

- Active Euthanasia involves deliberate acts to cause death (e.g., lethal injection) and remains illegal in India.

- Passive Euthanasia involves withholding or withdrawing life support from terminally ill patients and was legalised in 2018.

Legal Milestone:

- In the Common Cause v. Union of India (2018) case, a five-judge Constitution Bench ruled that the right to die with dignity is a part of the fundamental right to life under Article 21.

- The verdict permitted passive euthanasia and the creation of a “living will”—a legal document allowing patients to refuse life support if in a terminal or vegetative state.

Ethical and Constitutional Dimensions

- The plea raises significant questions about human dignity, bodily autonomy, and the limits of state intervention in end-of-life decisions.

- It also brings focus to judicial responsibility in expanding fundamental rights, especially in the context of terminal, untreatable illnesses.

Conclusion

The outcome of this case could have far-reaching implications on medical jurisprudence and the ethics of end-of-life care in India. If the Court recognizes rabies as an exception, it may set a precedent for disease-specific passive euthanasia protocols, expanding the practical application of the 2018 ruling.

DRAFT GUIDELINES ON PASSIVE EUTHANASIA IN INDIA

- 30 Sep 2024

Introduction

The Union Health Ministry of India has released new draft guidelines regarding passive euthanasia, aiming to address the complexities surrounding the withdrawal of life support for terminally ill patients. This move is significant, as it provides clarity for both medical professionals and patients regarding end-of-life care. The guidelines represent an effort to bridge the existing regulatory gap, ensuring ethical practices in sensitive medical decisions.

Understanding Euthanasia

Definition and Types

Euthanasia refers to the practice of intentionally ending a patient's life to alleviate suffering. The term originates from Greek, meaning "good death." Euthanasia can be categorized into several types:

- Active Euthanasia: Actively causing death, such as administering a lethal injection.

- Passive Euthanasia: Withholding life-sustaining treatments, allowing death to occur naturally.

- Voluntary Euthanasia: Conducted with the patient’s consent.

- Involuntary Euthanasia: Performed without patient consent, often in cases where the patient’s wishes are unknown.

Legal Context

While active euthanasia remains illegal in India, passive euthanasia was legalized by the Supreme Court in March 2018. This legal framework allows for the withdrawal of life support under specific circumstances.

Key Provisions of the Draft Guidelines

Conditions for Withdrawal of Life Support

The guidelines stipulate four critical conditions under which life support may be withdrawn:

- Brainstem Death: The patient must be declared brainstem dead as per the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act (THOA) of 1994.

- Medical Prognosis: The patient's condition must be advanced, indicating that aggressive therapeutic interventions are unlikely to yield benefits.

- Informed Refusal: The patient or their surrogate must document an informed refusal of continued life support following an understanding of the prognosis.

- Legal Compliance: Procedures must align with the legal principles established by the Supreme Court.

Decision-Making Process

The decision to withdraw life support requires a multi-tiered approach:

- Primary Medical Board (PMB): A group of at least three physicians must reach a consensus and explain the medical situation to the patient’s surrogate.

- Secondary Medical Board (SMB): A further validation by another set of three physicians, including one appointed by the district’s Chief Medical Officer, is necessary to confirm the PMB’s decision.

Advance Medical Directives

The guidelines emphasize the importance of advance medical directives, allowing individuals to document their healthcare preferences in case they lose decision-making capacity.

Ethical Considerations

Concerns from the Medical Community

While the guidelines aim to provide clarity, there are concerns regarding the legal scrutiny that doctors may face. The Indian Medical Association (IMA) has raised issues about the potential for undue stress on medical professionals, who historically have made these decisions in good faith without formal guidelines. They argue that placing such decisions within a regulatory framework might misinterpret standard medical practices.

Patient Autonomy and Dignity

The guidelines uphold the fundamental rights to autonomy, privacy, and dignity. Patients capable of making healthcare decisions can refuse life-sustaining treatments, even if such refusals may lead to death. The emphasis on informed decision-making seeks to ensure that patients can navigate their end-of-life choices with dignity.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Need for Stakeholder Feedback

The Health Ministry has solicited feedback from stakeholders, including healthcare professionals and the public, by October 20, 2024. This participatory approach aims to refine the guidelines and address any concerns regarding their implementation.

Balancing Ethical and Practical Considerations

The draft guidelines represent a significant step towards formalizing the process of passive euthanasia in India. They attempt to balance ethical considerations surrounding patient autonomy with the practical realities faced by healthcare providers.

Conclusion

The introduction of draft guidelines on passive euthanasia marks a pivotal moment in India's healthcare landscape. By clarifying the legal and ethical frameworks surrounding end-of-life decisions, these guidelines aim to enhance the dignity of terminally ill patients while providing essential support to healthcare professionals. The ongoing discourse surrounding these guidelines will be crucial in shaping their final form and ensuring their alignment with societal values and ethical norms.