India’s Ethanol Blending Success

- 26 Jul 2025

In News:

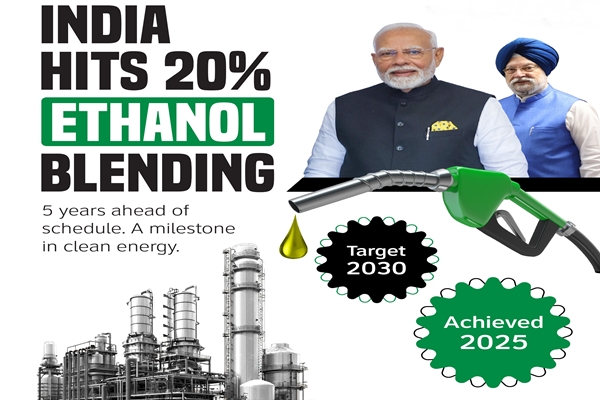

India has achieved a significant milestone by reaching 20% ethanol blending in petrol by March 2025, five years ahead of the original 2030 target under the National Policy on Biofuels (2018). This landmark achievement represents a transformative step in India’s journey toward energy self-reliance, environmental sustainability, and inclusive rural development.

Genesis and Policy Framework

The Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) Programme, launched in 2003 and significantly scaled up post-2014, aims to reduce dependence on imported crude oil, promote clean fuels, and support the agricultural economy. The programme is spearheaded by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas in collaboration with the Ministries of Agriculture and Food Processing. The National Policy on Biofuels expanded the permissible feedstocks for ethanol production, including sugarcane juice, B-molasses, damaged grains, maize, and agricultural residues.

Complementary initiatives like PM-JI-VAN Yojana, SATAT, PLI for ethanol production, and the National Bio-Energy Programme have accelerated infrastructure creation and second-generation (2G) ethanol technologies.

Progress and Scaling

The ethanol blending rate rose from 1.53% in 2014 to 8.17% in 2020–21, then to 12.06% in 2022–23, and reached 14.6% in 2023–24, culminating in the 20% target in early 2025. This scaling was supported by ?40,000 crore in investments and proactive procurement by Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) at pre-fixed prices, providing market stability for distilleries and farmers.

Over 17,000 fuel retail outlets now offer E20 fuel, with 400 E100 pumps operational. Automakers such as Honda and Hero MotoCorp have ensured vehicle compatibility with E20 fuels, ensuring consumer acceptance.

Economic and Rural Impact

The EBP programme has delivered strong macroeconomic and grassroots benefits. By reducing crude oil imports, India has saved substantial foreign exchange and improved energy security. At the micro level, farmers—particularly sugarcane and maize growers—have benefited from assured off-take and stable prices, reducing rural distress and boosting income security.

Moreover, the ethanol ecosystem has generated rural employment, supported local manufacturing under ‘Make in India’, and catalyzed investment in agro-industrial infrastructure.

Environmental and Climate Gains

India’s ethanol blending drive aligns with its climate commitments, especially its Net Zero by 2070 target. Ethanol blending has helped avoid 698 lakh tonnes of CO? emissions, reduced particulate pollution, and improved urban air quality. The shift also supports circular economy principles by utilizing agricultural surplus, foodgrains unfit for consumption, and residues—converting waste to wealth.

Future strategies emphasize 2G ethanol from non-food biomass and municipal waste, thereby reducing land and water stress associated with first-generation biofuels. Advanced technologies like lignocellulosic processing, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and ethanol-to-hydrogen conversion are in focus.

Conclusion

India’s early achievement of 20% ethanol blending demonstrates the success of coordinated policymaking, technological adoption, and stakeholder alignment. It serves as a model of how energy policy can intersect with rural prosperity, environmental stewardship, and industrial growth. Going forward, India’s biofuel roadmap not only reinforces its clean energy leadership but also strengthens its resolve for energy Atmanirbharta, sustainable development, and climate resilience.

Fossil Fuel Financing in 2024

- 28 Jun 2025

In News:

In a stark contradiction to global climate goals, the world’s 65 largest banks increased their fossil fuel financing by $162 billion in 2024, reaching a total of $869 billion, up from $707 billion in 2023, according to the Fossil Fuel Finance Report 2025. This trend threatens to derail global commitments under the Paris Agreement and undermines the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) roadmap to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

India’s Position:

Among global lenders, the State Bank of India (SBI) was the only Indian bank featured in the top 65, rising from the 49th to 47th position. SBI’s fossil fuel financing increased modestly by $65 million, taking its 2024 total to $2.62 billion. Cumulatively, between 2021 and 2024, SBI extended $10.6 billion to fossil fuel projects. In contrast, JPMorgan Chase topped the global list with $53.5 billion in 2024 alone.

Despite this, SBI has also signalled intent to transition. It has pledged to become net zero by 2055, and aims to ensure that 7.5% of its domestic advances are green by 2030. As of March 2024, SBI had sanctioned ?20,558 crore in sustainable finance. However, this dual-track financing model raises questions about the coherence of India's green finance agenda.

Global Setbacks and Policy Rollbacks

2024 witnessed a rollback in climate-related financial commitments, particularly in the United States. The withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, scheduled to take effect in 2026, was accompanied by policy shifts like exiting the Net Zero Banking Alliance and the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). Major banks such as Wells Fargo abandoned their net-zero commitments, signaling a broader retreat from climate-aligned finance.

This global trend is no longer confined to North America. European banks, traditionally viewed as progressive, also weakened fossil fuel exclusion policies. The result: a global rise in fossil fuel merger and acquisition financing, which reached $82.9 billion in 2024, up by $19.2 billion from 2023. Although M&As do not directly add infrastructure, they consolidate fossil fuel power at a time when the world urgently needs to pivot to renewables.

Indian Banks and the Coal Dilemma

Indian financial institutions, barring a few exceptions like Federal Bank and RBL Bank, lack explicit coal exclusion policies. According to Climate Risk Horizons, this constitutes a major blind spot. The economics of energy is shifting — renewables and storage are now often cheaper than coal, making continued fossil fuel investments financially and environmentally risky.

Conclusion

The rise in fossil fuel financing reflects a disconnect between climate rhetoric and financial action, threatening the global transition to clean energy. For India, this highlights the need for a coherent climate finance strategy, integrating environmental, financial, and developmental priorities. As a signatory to the Paris Agreement and a G20 economy, India must not only align public finance with green goals but also push for global financial reforms that discourage fossil fuel dependencies and reward sustainable investments.